Space exploration and the Cold War

Following the end of World War 2 two nations competed for military and political supremacy in the world: The United States of America and the Soviet Union. With diametrically opposed views on politics and economics these nations soon found themselves competing against each other while diplomatic tensions between them began to rise. This state of tension is known as the Cold War. During the Cold War the USSR and USA started competing against each other in space exploration. This competition is known as the Space Race.

1 of 6

In those days space exploration was primarily motivated by military and political goals. Military, the technology developed during the space race was used to improve each nation's rocket arsenal. Politically the space race, with it’s many premiers, was viewed as a propaganda tool to weaken the enemy nation.

2 of 6

The Sixties were a decade of contrasts. They saw enormous political, social and cultural change and have been seen as a nostalgic era of peace and liberalism, overshadowed by a dark cloud of hatred, oppression and wanton excess. They began, ominously, under the longest shadow of the Cold War. Younger generations, inspired by the unequal conservative norms of the time, as well as an increasingly unpopular war brewing in Vietnam, cultivated a social revolution which swept across much of the western world.

3 of 6

Although the Cold War had its downsides (accusations of treason, spying, a costly American involvement in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts, and a massive propaganda machine), it undeniably produced some serious innovation in technology and industry. The buildup of both the Soviet and American defense systems was another result of these tensions, as was a race to produce and stockpile nuclear arms.

4 of 6

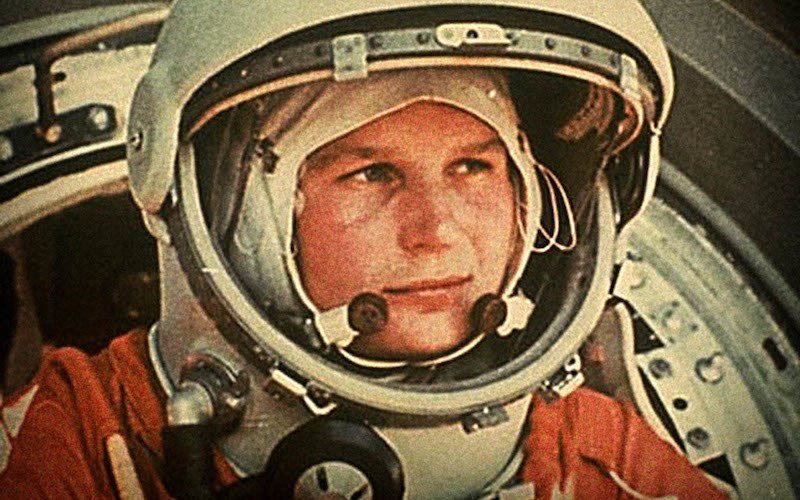

Humanity had advanced enormously between the end of the Fifties and the close of the Sixties, in a thousand social, cultural, political and technological ways. It would have been impossible to imagine on the eve of Yuri Gagarin's orbital flight that within such a short span of time the techniques and tools of rendezvous, docking, spacewalking and reaching the Moon would have been tried, tested and mastered.

5 of 6

The militaristic aspect of the Cold War was frighteningly intense, with a series of treaties, wars, and other events that solidified the opposition between the two countries. War was never officially declared, hence the term Cold War, but these countries and their allies soon had divisive political and technological agendas to meet.

6 of 6

Several decades passed before the end of the Cold War; between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s introduction of glasnost (transparent and open government) and perestroika (economic restructuring) and President Ronald Reagan’s influence, the Cold War petered out in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought further realizations of capitalism and a free market to the former Soviet states.

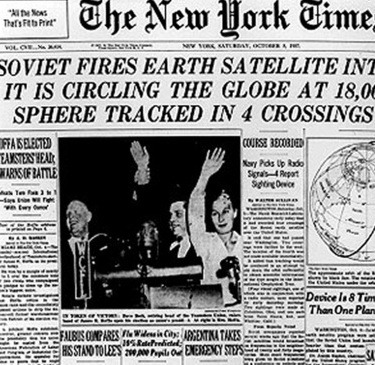

The launch of Sputnik 1 proceeded as planned on October 4, 1957, thus cementing the Soviet Union’s place in history as the first country to launch an artificial satellite into orbit. The Soviet Union notified observers around the world to watch for the satellite, which could be seen from the ground through binoculars or telescopes as it passed through the night sky. Additionally, the radio signal from Sputnik 1 could be heard with a common shortwave radio. This beeping signal quickly became a symbol of the Soviet Union’s technological prowess.

1 of 4

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev used the fact that his country had been first to launch a satellite as evidence of the technological

power of the Soviet Union and of the superiority of communism. He repeated these claims after Yury Gagarin’s orbital flight in 1961.

2 of 4

Even before the first satellite was launched, U.S. leaders recognized that the ability to observe military activities around the world from space would be an asset to national security. Following on the success of its photo reconnaissance satellites, which began operation in 1960, the United States built increasingly complex observation and electronic-intercept intelligence satellites. The Soviet Union

also quickly developed an array of intelligence satellites, and later a few other countries instituted their own satellite observation programs.

3 of 4

The New York Times pointed out that Sputnik was eight times heavier than the device the U.S. government hoped to place in orbit. Americans became edgy and downright apprehensive about their future. One of the core beliefs that drove American society was the idea that U.S. scientists and engineers were the world’s best—and here the Russians were, outperforming them. The Times reported that Dr. Joseph Kaplan, who was chairman of the U.S. section of the International Geophysical Year, called the Russian achievement “fantastic.”

4 of 4

Concerned voices intruded on the admiration for the Russian accomplishment. In an open letter to the New York Herald Tribune, economist Bernard Baruch wrote about “The Lessons of Defeat”: ‘While we devote our industrial and technological power to

producing new model automobiles and more gadgets, the Soviet Union is conquering space. While America grumbles over taxes and cuts the cloak of its defense to the cloth of its budget, Russia is launching intercontinental missiles. Suddenly, rudely, we are awakened to the fact that the Russians have outdistanced us in a race which we thought we were winning. It is Russia, not the United States, who has had the imagination to hitch its wagon to the stars and the skill to reach for the moon and all but grasp it. America is worried. It should be.’

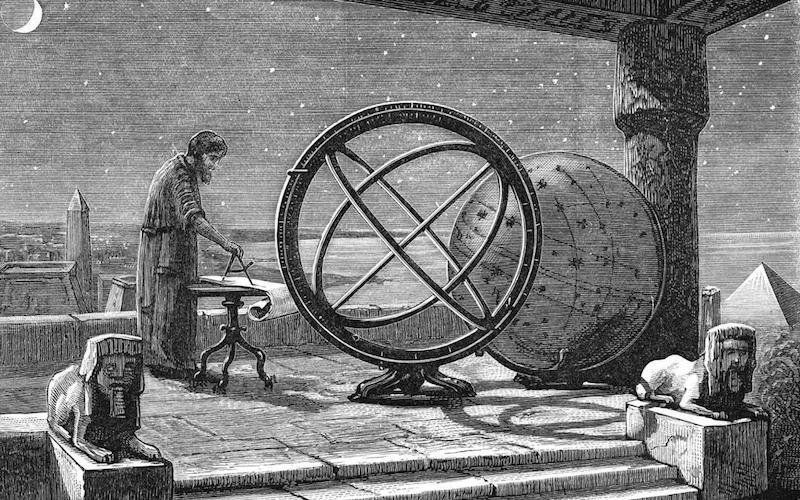

Astronomy in the Ancient Times

Astronomy is a science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. Humanity has studied astronomy since ancient times. Astronomy, as an orderly pursuit of knowledge about the heavenly bodies and the universe, did not begin in one moment at some particular epoch in a single society. Every ancient society had its own concept of the universe (cosmology) and of humanity's relationship to the universe. In most cases, these concepts were...

Astronomy in the Modern Times

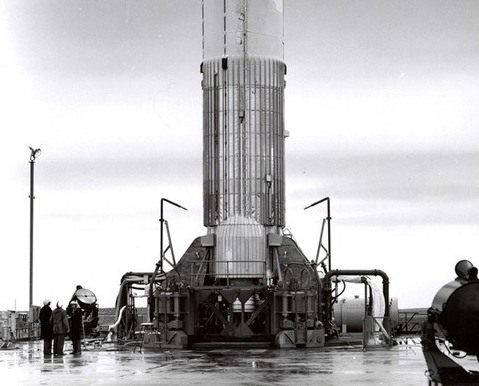

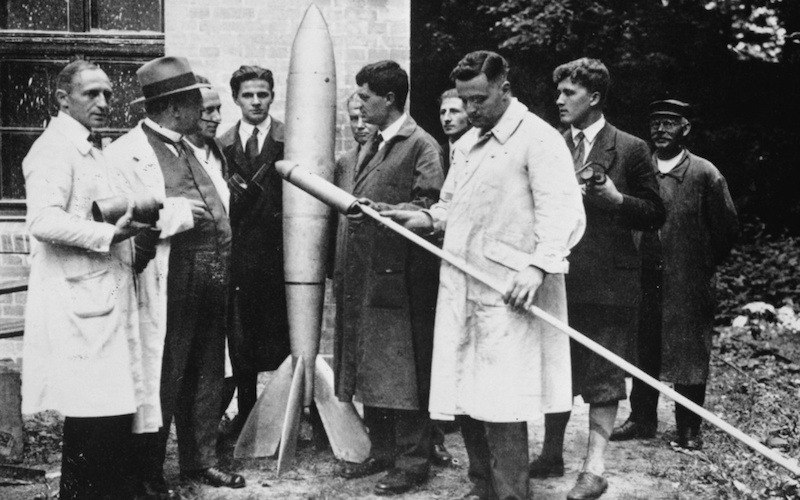

History of Rockets

Space Race

Space Agencies

Science fiction and space exploration

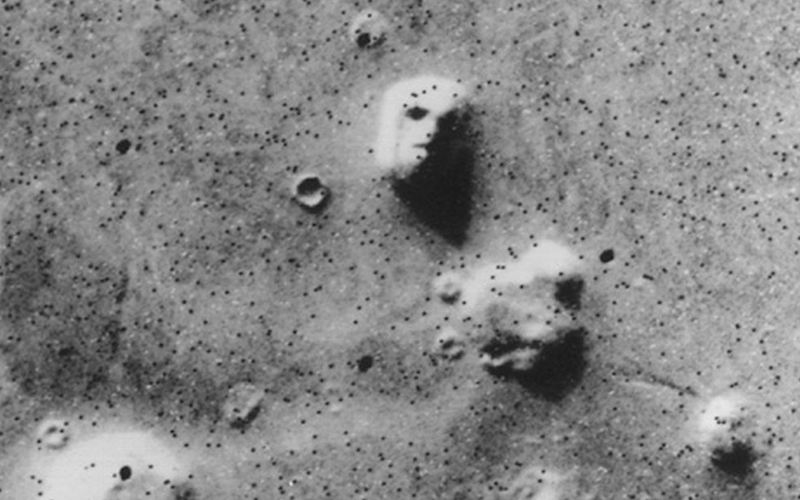

Exploration of Mars

Exploration of the inner solar system

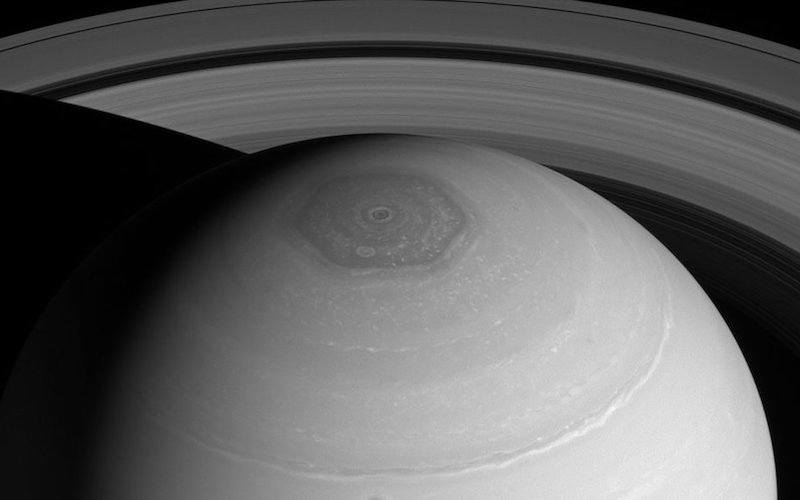

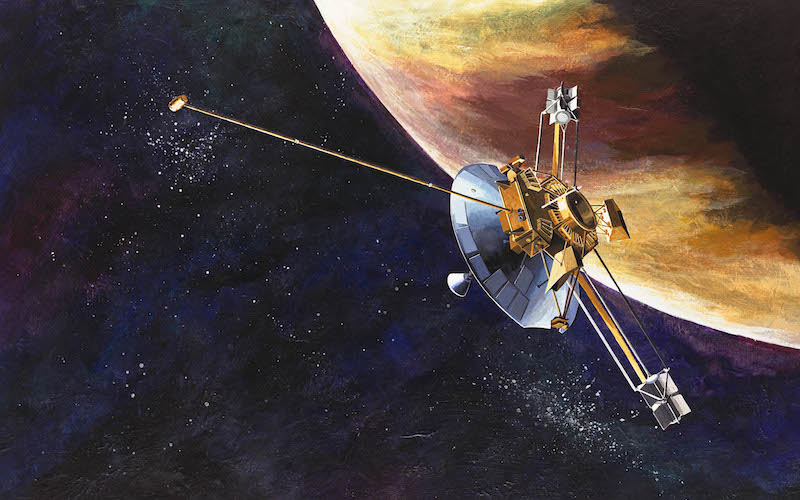

Exploration of the outer solar system

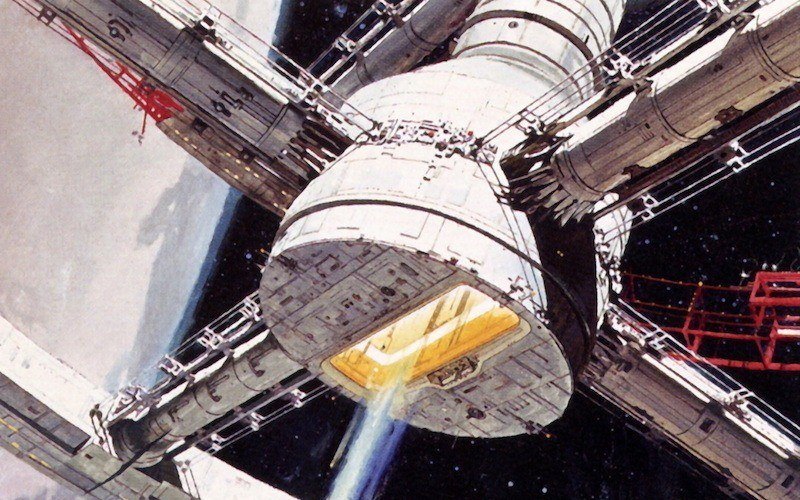

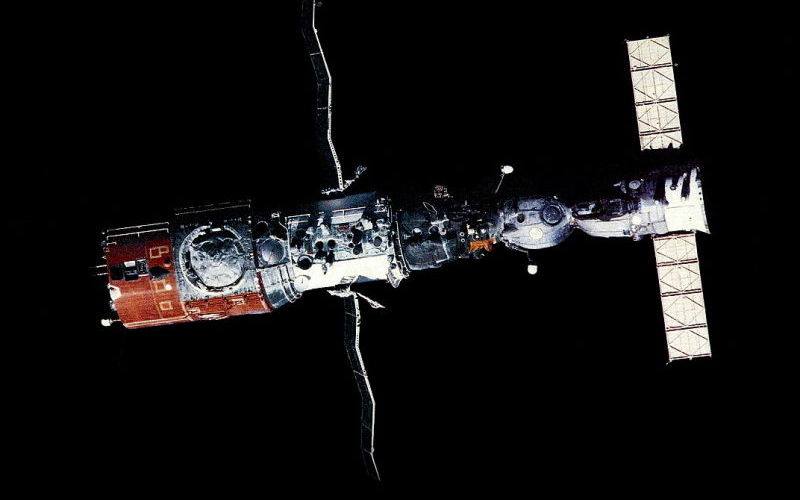

Modern orbital space exploration

History of Satellites

One of the most dramatic moments of the twentieth century occurred on October 4, 1957. The Soviet Union sent a small shiny sphere with four long antennas into space. They called it Sputnik I. Sputnik is a Russian word that means “traveling companion.” The satellite traveled so fast that its ballistic flight continued all the way around Earth.

The Future of Space Exploration

While the current lunar exploration initiative has been justified as a “stepping stone” toward Mars, human missions to Mars represent a major step up in complexity, scale, and rigour compared to lunar missions.

- Cynthia Phillips, Shana Priwer, Space exploration for dummies, Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana, 2009

- Erik Gregersen, Unmanned space missions: An explorer’s guide to the universe, Britannica Educational Publishing in association with Rosen Educational Services, New York, 2010

- Samuel Willard Crompton, Sputnik/Explorer : The race to conquer space, Chelsea House Publishing, New York, 2007

- Ben Evans, Escaping the Bonds of Earth: The Fifties and the Sixties, Praxis Publishing, Chichester, UK, 2009