Astronomy in the Modern Times

The fifteenth century in Europe was remarkable in that two great intellectual movements began to sweep across the continent almost

simultaneously: the Renaissance and free scientific inquiry—particularly astronomy.

1 of 2

The Renaissance contributed to the growth of new ideas in that it encouraged art, literature, architecture, and exploration. This led

to technological developments and the invention of such things as the mariner's compass (the magnetic compass). Ultimately these

technological developments led to the astronomical telescope.

2 of 2

A few writers on astronomy are worth mentioning, not because they contributed to the Copernican revolution that was to come but because they kept alive the flow of new ideas. Among them were Celio Calcagnini, Johannes de Monte Regio, George Rohrbach, Girolamo Fracastoro, and Giovanni Battista Amiri.

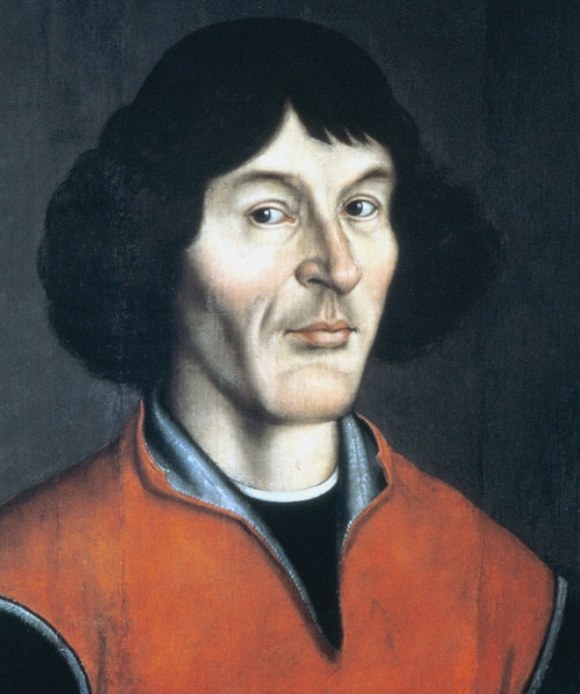

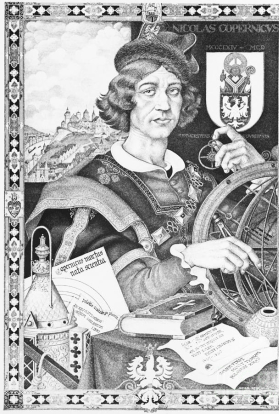

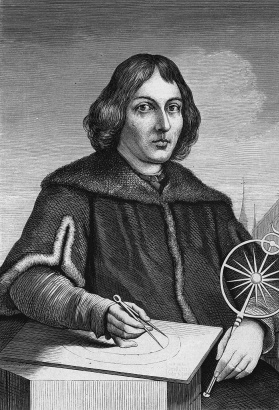

One of the founding fathers of modern astronomy, Nicolaus Copernicus, made waves for his rejection of the Earth as the literal center of the universe. Based on an elegant theoretical model of the geometry of the solar system and the motions of the planets, he eventually came up with the idea that the Sun was at the center of the solar system, not the Earth. Copernicus first presented his heliocentric theory in a preliminary thesis that was never published. He later expounded upon this thesis in a work called De revolutionibus

orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which wasn’t published until 1543, the year of his death.

1 of 7

Copernicus, deeply concerned about his commitments to his church and his devotion to the Pope, was very reluctant to publish his heliocentric theory, even though he was strongly urged to do so by some church dignitaries themselves. Most people think that Copernicus delayed publishing his ideas because he was afraid to go against the powerful religious forces of the day — then again, he could also have just feared looking foolish.

2 of 7

Copernicus had started his Italian schooling at the University of Bologna, where he studied with the astronomer Domenico Maria

de Novara, who was a very careful observer. Before leaving Italy for the first time Copernicus spent a year at the University of Rome, where he gave a course on mathematics. When Copernicus returned to Italy he went to Padua where he continued his studies of law, mathematics, and medicine, receiving a degree of Doctor of Canon Law. By the time he left Italy he was a master of theology and knew the classics thoroughly; he had also mastered all the mathematics and the astronomy known at that time.

3 of 7

When Copernicus returned to his canonry duties in Ermland, he was delighted by the leisure he had to pursue his astronomical studies and by the small demands on his time made by his clerical commitments. Copernicus, untrained an observer as he was, discovered

many celestial phenomena that are greatly simplified by a heliocentric solar system, and so he decided to devote the rest of his life to formulating a heliocentric system that would be acceptable to everyone, even to the Pope. He was driven by the conviction that if one accepted, that the earth and all the other planets revolve around the sun, the astronomy of the solar system would be simplified.

4 of 7

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in Thorn on the Vistula. He was educated as an Aristotelian and, in his early years, accepted the Ptolemaic model of the solar system, as taught at the University of Cracow by the outstanding authority on astronomy, Albert Brudzew (Brudzewski), who had written the first of a series of commentaries on the outstanding book on planetary motions by Rohrbach.

5 of 7

Whether Brudzewski had imbued Copernicus with doubt about Ptolemy's theory is not clear, but Copernicus' thinking about the motions of the earth and the planets was influenced much more by his travels in Italy than by his studies at Cracow. When Copernicus returned home from Cracow, his maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, Bishop of Ermland, made him a canon of the Church in the Cathedral of Frauenburg. Watzenrode insisted, however, that his nephew spend time at various Italian universities before assuming the canonry.

6 of 7

In his dedication to Pope Paul III at the beginning of his great book, Copernicus remarks that he was prompted to develop a new

model of the solar system by the inadequacies and inconsistencies he found in the Ptolemaic solar system. In his dedication to

Pope Paul III, Copernicus includes a passionate and poetic panegyric to the sun: "How could the light [the sun] be given a better place to illuminate the whole temple of God? The Greeks called the Sun the guide and soul of the world; Sophocles spoke of it as the All-seeing One; Trismegistus held it to be the visible embodiment of God. Now let us place it upon a royal throne, let it in truth guide the circling family of planets, including the Earth. What a picture—so simple, so clear, so beautiful."

7 of 7

One of the cardinals in Rome gave a lecture to the Pope on Copernicus' heliocentric theory, and sent his secretary to Frauenburg to obtain copies of Copernicus' proof that the earth revolves around the sun. In a letter to Copernicus he stated "If you fulfill this wish of mine you will learn how deeply concerned I am of your fame, and how I endeavor to win recognition of your deed. I have closed you in my heart." This letter was equivalent to an official sanction from the Church because the cardinal was its chief censor. This was followed by the encouragement from the Bishop in Copernicus' diocese that Copernicus' book be published as a duty to the world.

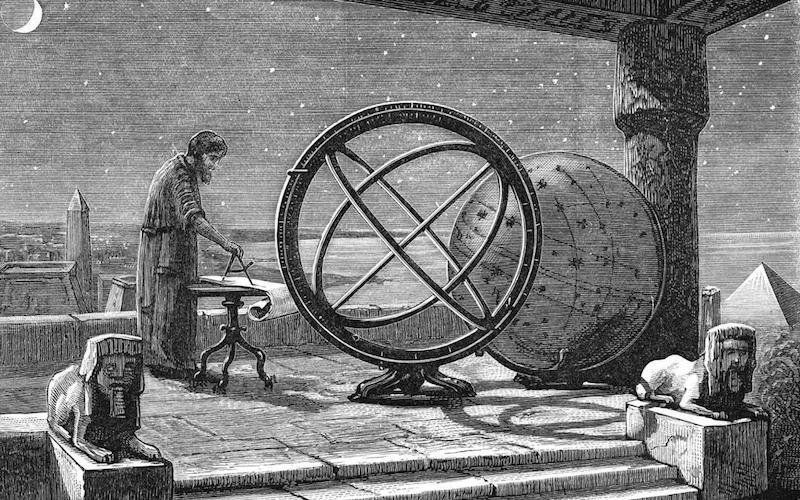

Astronomy in the Ancient Times

Astronomy is a science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. Humanity has studied astronomy since ancient times. Astronomy, as an orderly pursuit of knowledge about the heavenly bodies and the universe, did not begin in one moment at some particular epoch in a single society. Every ancient society had its own concept of the universe (cosmology) and of humanity's relationship to the universe. In most cases, these concepts were...

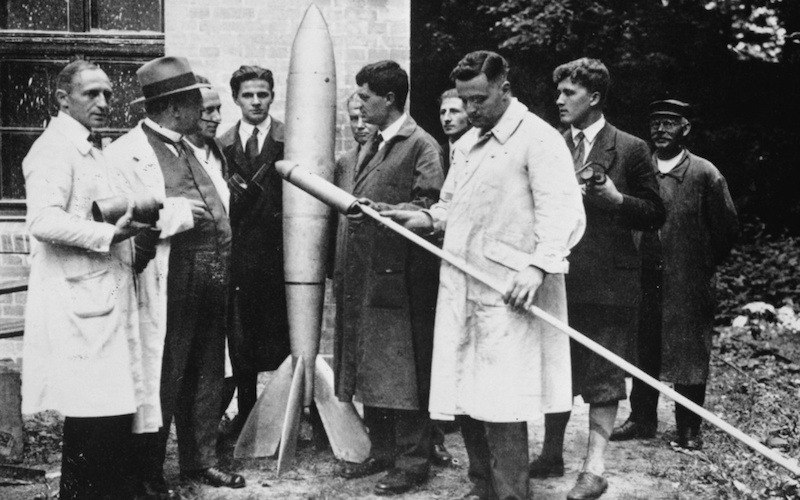

History of Rockets

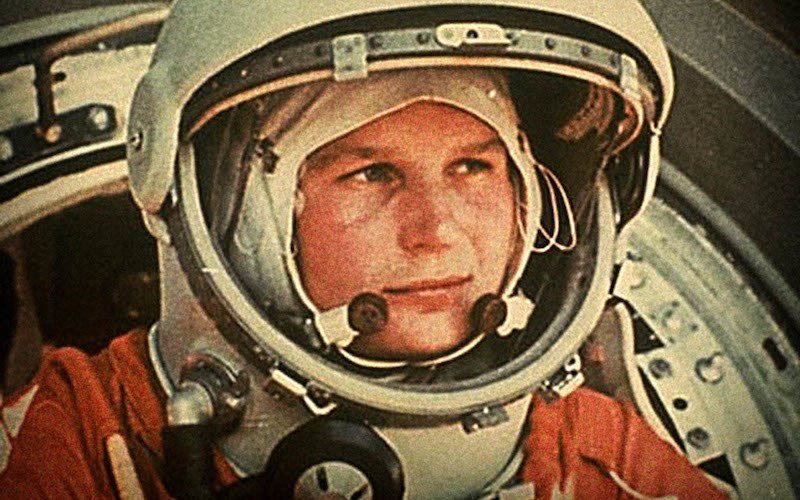

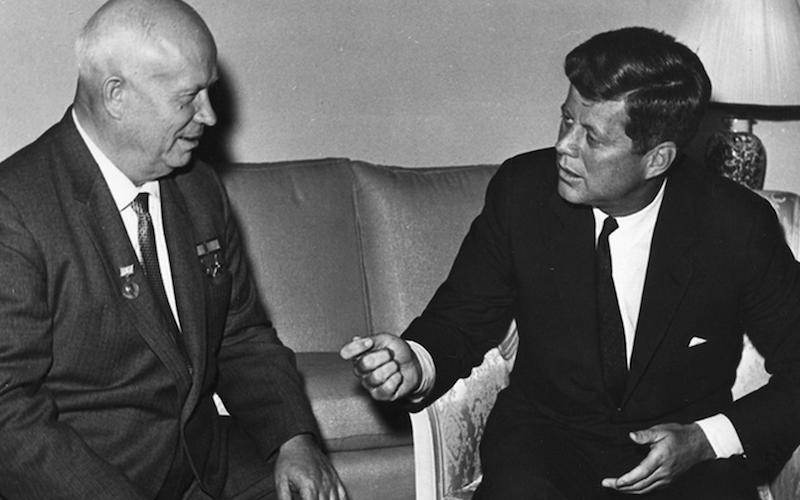

Space Race

Space exploration and the Cold War

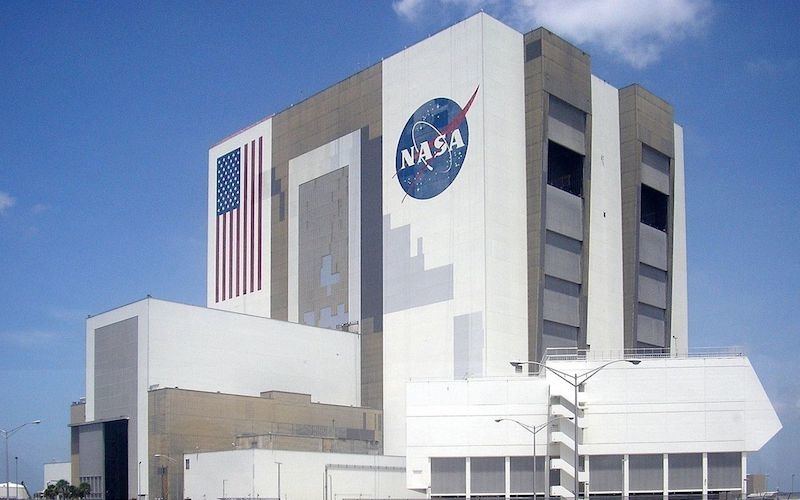

Space Agencies

Science fiction and space exploration

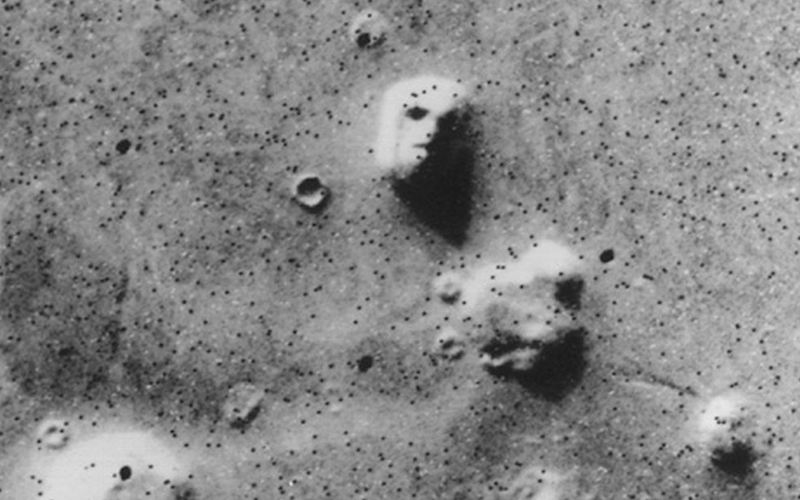

Exploration of Mars

Exploration of the inner solar system

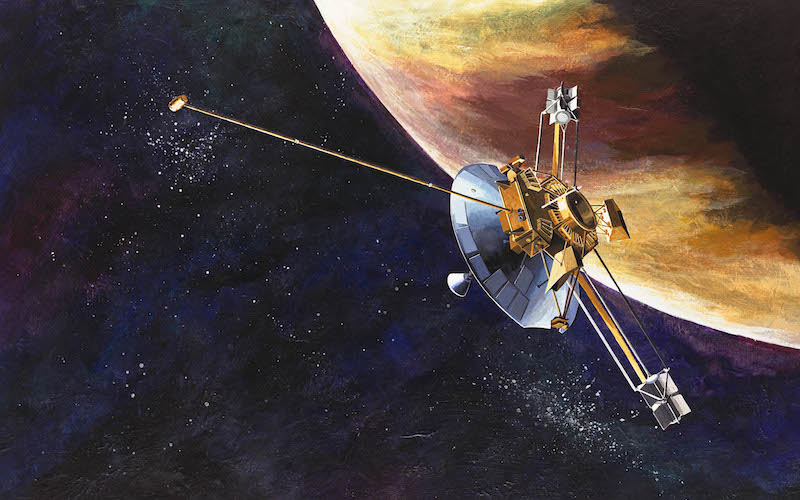

Exploration of the outer solar system

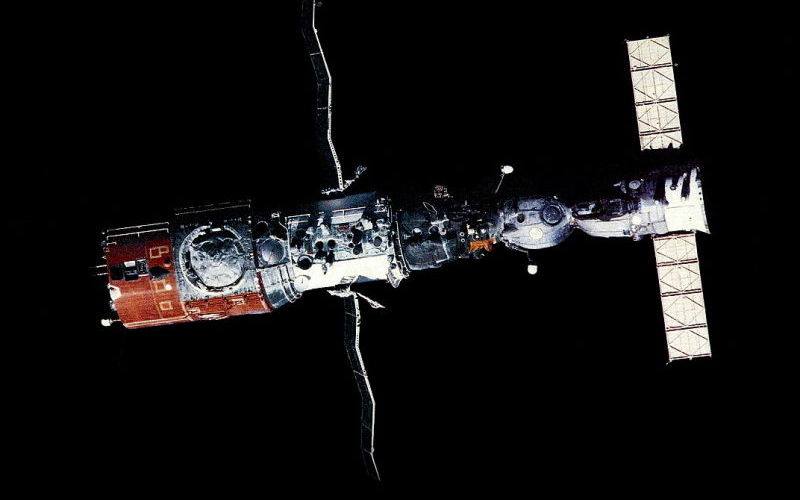

Modern orbital space exploration

History of Satellites

One of the most dramatic moments of the twentieth century occurred on October 4, 1957. The Soviet Union sent a small shiny sphere with four long antennas into space. They called it Sputnik I. Sputnik is a Russian word that means “traveling companion.” The satellite traveled so fast that its ballistic flight continued all the way around Earth.

The Future of Space Exploration

While the current lunar exploration initiative has been justified as a “stepping stone” toward Mars, human missions to Mars represent a major step up in complexity, scale, and rigour compared to lunar missions.

- Cynthia Phillips, Shana Priwer, Space exploration for dummies, Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana, 2009

- Lloyd Motz, Jefferson Hane Weaver, The story of astronomy, Perseus Publishing, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1995