Exploration of the inner solar system

The first obvious place to send a space probe was the Moon. It’s only 384,400 km away, so both NASA and the former Soviet Union launched unmanned lunar missions in the 1960s. Luna 3 was first to send photographs of the back side of the moon, which we cannot see with telescopes from Earth. Probes from the United States named Ranger 6, Ranger 7, and Ranger 8 took a total of 17,267 pictures before they each smashed on the Moon. These pictures confirmed that there were thousands of craters too small to be seen clearly from Earth.

1 of 3

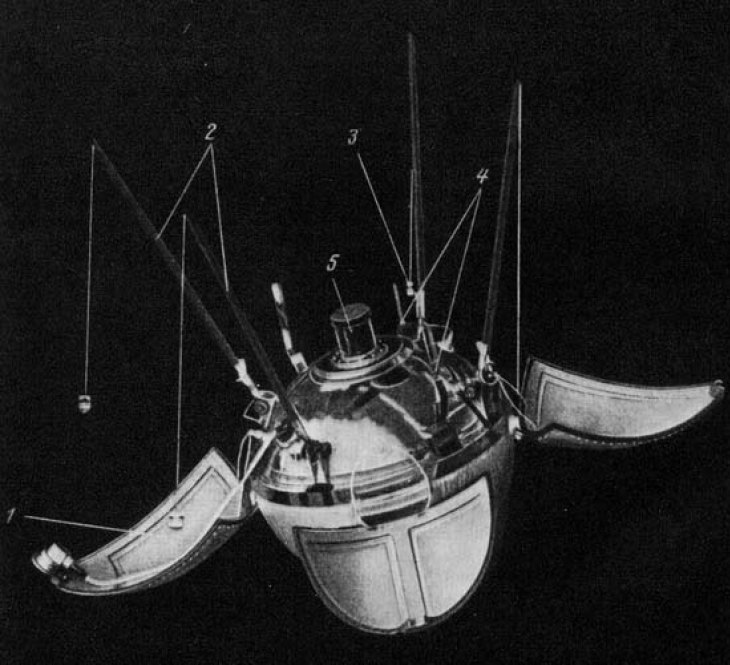

The Luna program was launched in the highly competitive political climate of the 1960s. Luna 9 became the first spacecraft to soft-land on the Moon, proving that the surface is firm. Though other spacecraft failed just before and after it, Luna 10 became the first spacecraft to enter lunar orbit. Luna 11 and 12 added more orbital maps. On December 24, 1966, Luna 13 landed on the Moon and provided TV panoramas. Luna 14 was the last of this series and entered orbit on April 10, 1968.

2 of 3

A total of nine Rangers were launched between 1961 and 1965. All but the last three failed, though Ranger 4 did become the first artificial object to impact the Moon’s far side. Ranger 7 relayed the first close-range lunar photos. Ranger 8 provided more coverage, and Ranger 9 sent images shown live in the first television spectacular about the Moon.

3 of 3

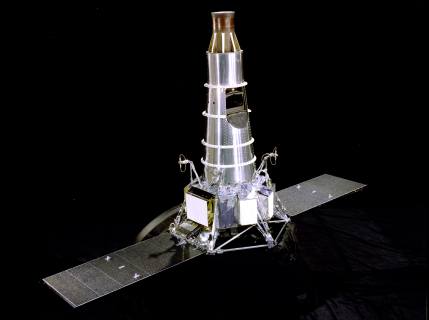

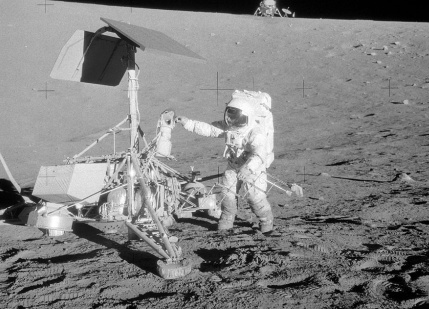

The first Surveyor soft-landed on the Moon in June 1966. Also that summer, the first of five Lunar Orbiters was launched to take photos and test ground tracking systems. Surveyor 2 crashed, but Surveyor 3 landed in April 1967. The Apollo 12 crew landed nearby in and retrieved a piece of it. Surveyor 4 crashed, and 5 landed in the Sea of Tranquility. Surveyor 6 landed and took off from the surface, the first American spacecraft to do that. The last Surveyor reached the Moon on January 10, 1968. It landed in the crater Tycho.

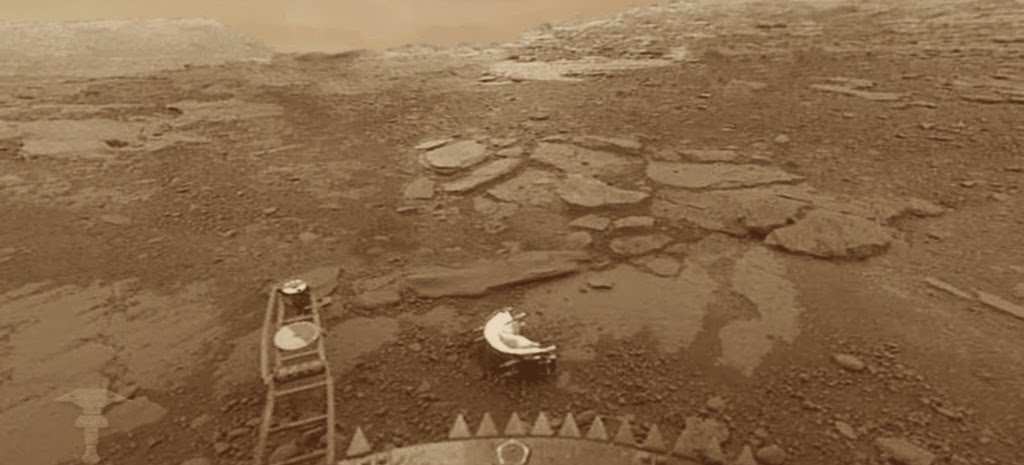

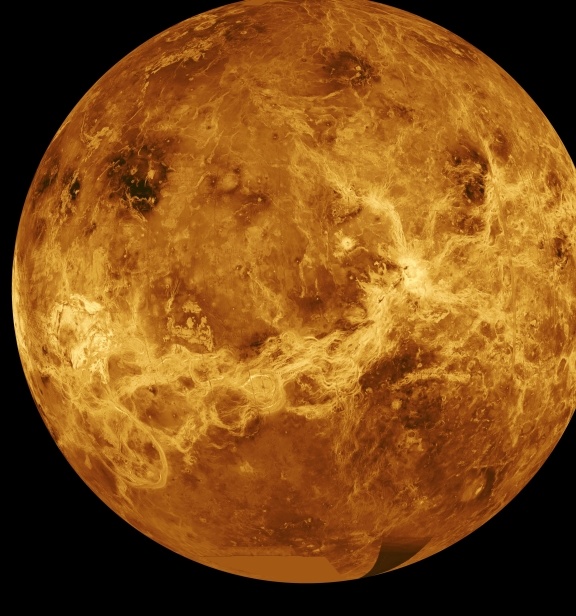

The Soviet Union may’ve been unlucky when it came to exploring Mars but it experienced dramatic success with missions to Earth’s other neighbor: Venus. The Venera program ran from 1961 through 1984 and boasted 10 landing probes that gathered data on Venus’s surface, as well as 13 flyby or orbital probes that sent data home from the atmosphere surrounding Venus. The landers, in particular, were technological marvels that were able to withstand the extreme conditions at Venus’s surface: high pressure, temperatures hot enough to melt lead, and a corrosive atmosphere.

1 of 4

Probes to the Moon or to Mars were capable of surviving and transmitting data for weeks or months (or, in some cases, years), but the surface conditions on Venus were much less hospitable. Venus’ atmosphere is so thick that the atmospheric pressure at the planet’s surface is almost 100 times that at the Earth’s surface. Venus’s thick clouds trap the Sun’s heat, resulting in a surface temperature of about 260 degrees Celsius. Because of this the space probes that managed to reach Venus’s surface lasted for only around an hour, so the amount of data they were able to return home was limited.

2 of 4

Ironically, although surface conditions on Venus are much harsher than on Mars, landing on the former is actually easier than landing on the latter. The thick atmosphere means that a series of parachutes can slow a spacecraft down from interplanetary speeds to a safe landing speed without having to rely on complex retrorockets to be fired before landing (like the ones needed on Mars due to the planet’s thin atmosphere).

3 of 4

Venus is a tremendous challenge for spacecraft. Many of the 19 Soviet missions failed, but Venera 4 was the first spaceship to enter the atmosphere of another planet; Venera 7 was the first to land on another planet; and Venera 9 transmitted the first photographs from the surface of another planet.

4 of 4

Models of Venus evolved from steamy jungles to dry deserts to global oceans of carbonated water. In 1967, Carl Sagan suggested that “float bladder macro-organisms” might live in the atmosphere. Radar studies of the surface in 1970 detected dark, circular regions that were interpreted as giant impact basins. All of these models would be found lacking before the end of the 1970s.

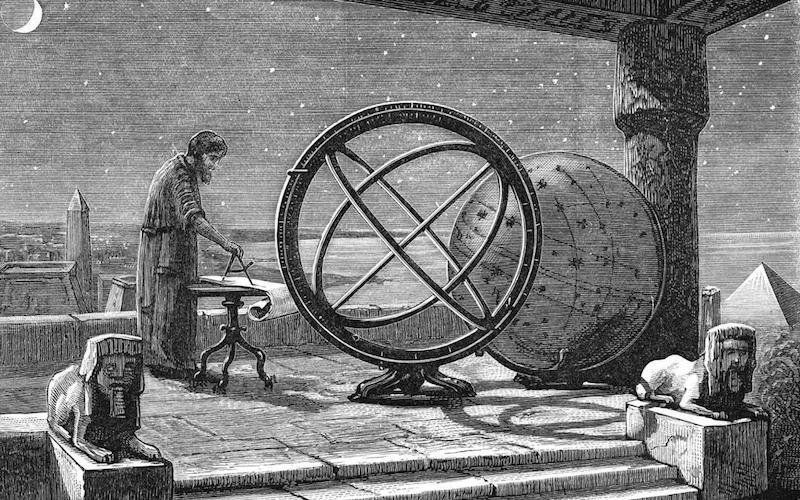

Astronomy in the Ancient Times

Astronomy is a science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. Humanity has studied astronomy since ancient times. Astronomy, as an orderly pursuit of knowledge about the heavenly bodies and the universe, did not begin in one moment at some particular epoch in a single society. Every ancient society had its own concept of the universe (cosmology) and of humanity's relationship to the universe. In most cases, these concepts were...

Astronomy in the Modern Times

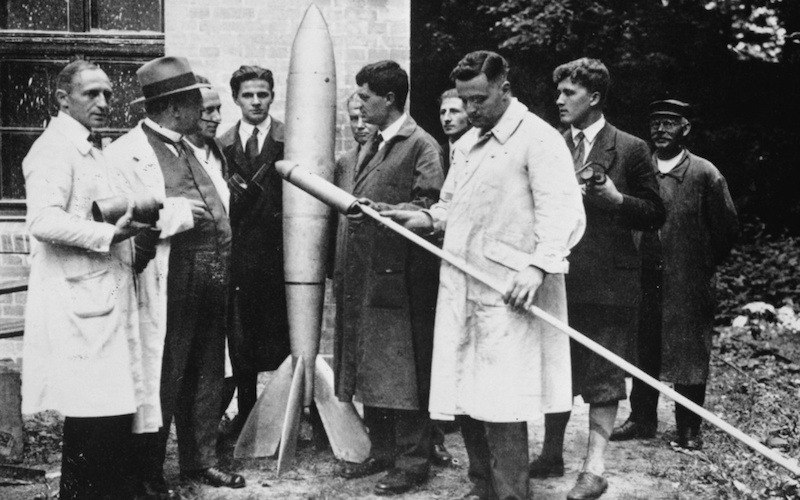

History of Rockets

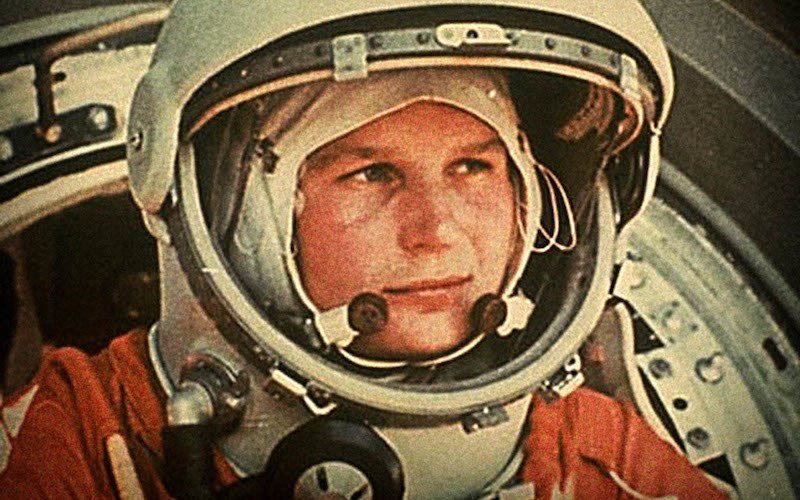

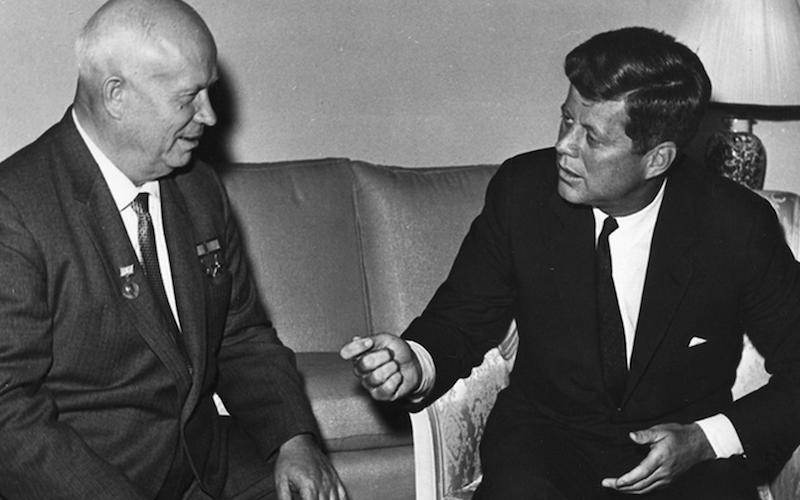

Space Race

Space exploration and the Cold War

Space Agencies

Science fiction and space exploration

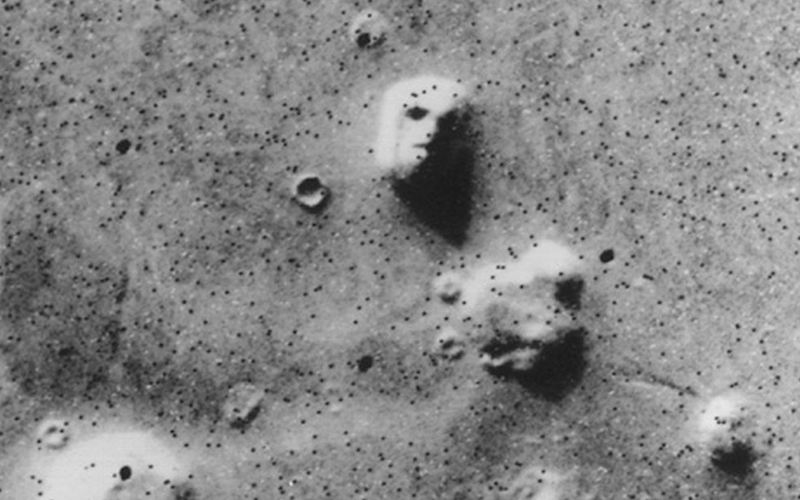

Exploration of Mars

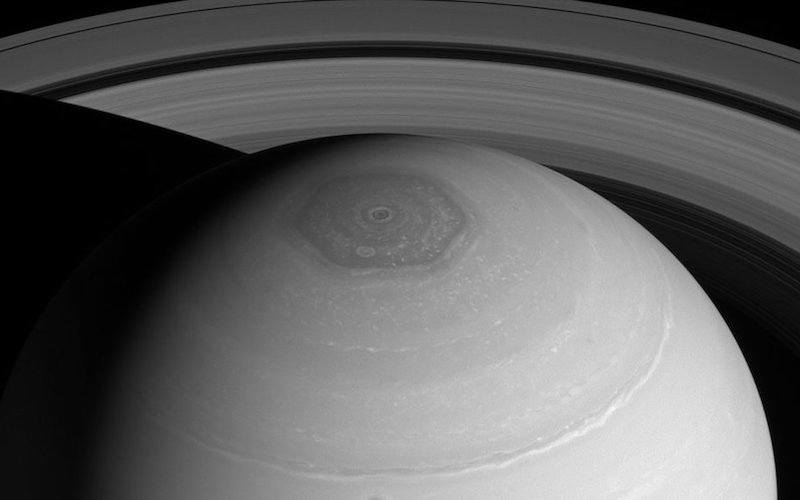

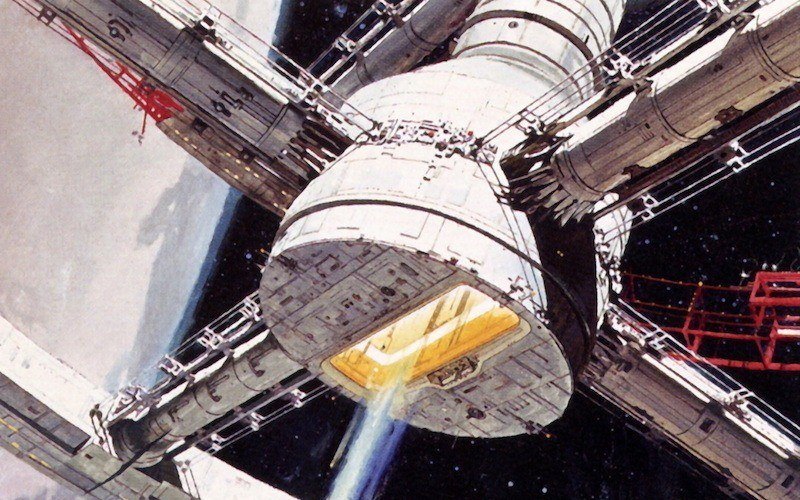

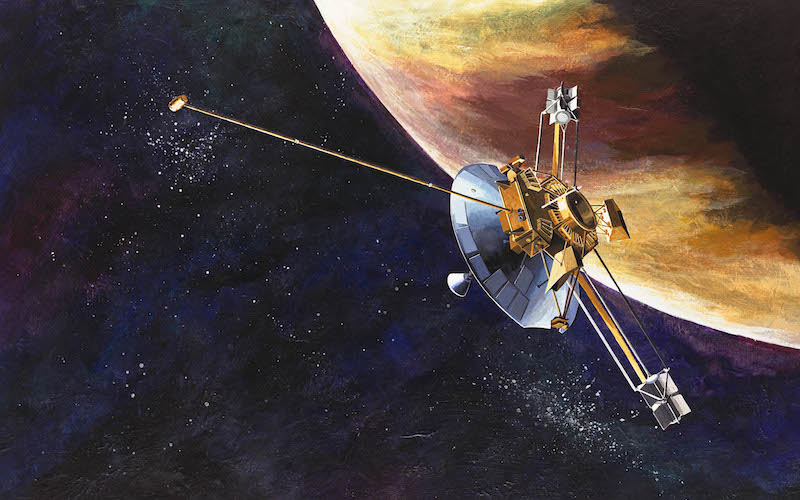

Exploration of the outer solar system

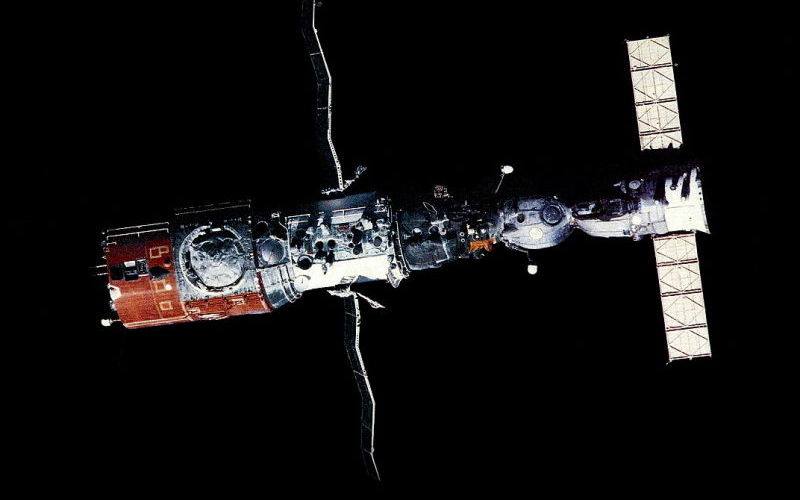

Modern orbital space exploration

History of Satellites

One of the most dramatic moments of the twentieth century occurred on October 4, 1957. The Soviet Union sent a small shiny sphere with four long antennas into space. They called it Sputnik I. Sputnik is a Russian word that means “traveling companion.” The satellite traveled so fast that its ballistic flight continued all the way around Earth.

The Future of Space Exploration

While the current lunar exploration initiative has been justified as a “stepping stone” toward Mars, human missions to Mars represent a major step up in complexity, scale, and rigour compared to lunar missions.

- Cynthia Phillips, Shana Priwer, Space exploration for dummies, Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana, 2009

- Kim Masters Evans, Space Exploration Triumphs and tragedies, Gale Publishing, Farmington Hills, Michigan, 2009

- Peter Jedicke, Great moments in space exploration, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007

- Marianne J. Dyson, Twentieth century space and astronomy: Decade by decade, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007