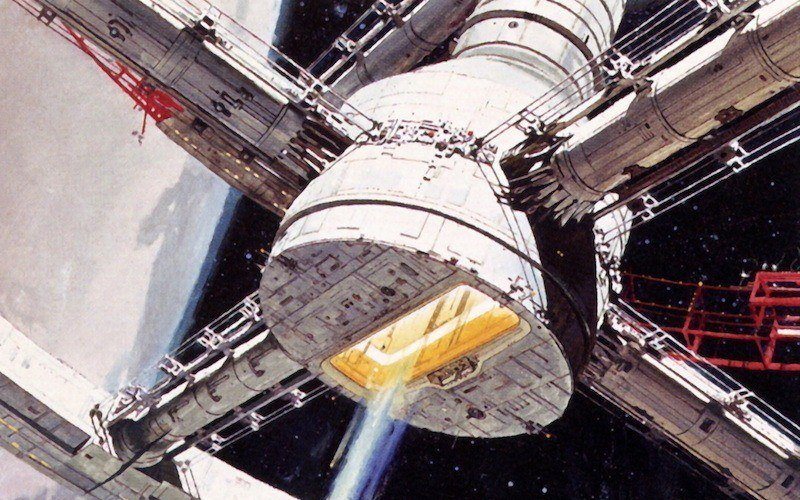

Science fiction and space exploration

Dreams of space – of not-Earth – have inspired humanity over the ages. Dream-inspired humans made space travel a reality. Without our dreams, there would be no space programs anywhere. Artistic, religious, philosophical, and ethical perspectives are

not frills or mere add-ons to space activities. They are absolutely essential parts of all aspects of all space endeavors. At the same time, without the science and technology that enables humans to loose the bonds of Earth, humans would still only be dreaming of space while never going to the Moon and beyond.

1 of 5

The idea that there are worlds and beings not of this Earth that interact with humans and Earth is very widespread across the globe and has persisted for a very long time. Modern space fiction is just one current way by which very old stories are being told and retold dressed up with contemporary ideas and technologies. These old stories influence the way we think about current space exploration.

2 of 5

Probably the iconic figure for flight in Western cultures is Icarus, the Greek who, with his father, Daedalus, fashioned wings so that he and his father could fly like the birds, something they were totally unable to do with their wingless, flightless natural bodies. So, as is always the case, humans first imagine doing something impossible – flying – and then develop the technologies that enable their dreams to come true.

3 of 5

One of the best-known Japanese folk tales is about Kaguya Hime. A bamboo cutter discovered a baby girl inside a bamboo shoot. He took the baby home, where he and his wife reared the baby as their own. When she grew up, she revealed that she was not from Earth and was transported back to the Moon from which she came. Her story, and her return to the Moon, is repeatedly told in Japan. In the summer of 2007, JAXA (the Japanese space agency) launched a lunar orbiter. JAXA asked the Japanese public what the name of the orbiter should be, and Kaguya Hime was the overwhelming choice.

4 of 5

Another popular folktale from China, Korea, and Japan is told every summer on the seventh night of the seventh month. It celebrates what appears to be the annual meeting of the stars Vega and Altair that are otherwise separated by the Milky Way.

According to the folk story, Vega is a seamstress and Altair is an ox-herder. They love each other but are separated from one another and only allowed to meet briefly once a year, and then must part once again.

5 of 5

One of the most important developments in science fiction was the emergence of cyberpunk literature spearheaded by William Gibson’s Neuromancer. It was inspired by contemporary and emerging advances in electronic communication technologies, biotechnology, and nanotechnology, combined with deep anxiety about the environmental and social consequences of these and other developments. Cyberpunk treats science and technology critically and ironically.

Space fiction, almost by definition, involves voyages of discovery. However, well before the modern era, certain cultures had stories about voyages of discovery, while other cultures had no such stories at all. In the former, heroes leave home, travel through strange times and places, overcome many adversities and have many exceptional experiences before returning home again, enlightened by the process.

1 of 5

The basic archetypical stories for Western cultures are the Iliad and the Odyssey, first composed between 800 and 600 BCE. The Odyssey, recounting 20 years of travel by Odysseus (Ulysses, in Latin), is a prime example.

2 of 5

In the Abrahamic Bible, the first book, Genesis, is immediately followed by Exodus: departure happens soon after Creation. The story of Moses leading the Jewish people to the Promised Land – and the belief in the existence of a Promised Land that is rightfully theirs – is an unfinished narrative of travel and travail in Western cultures.

3 of 5

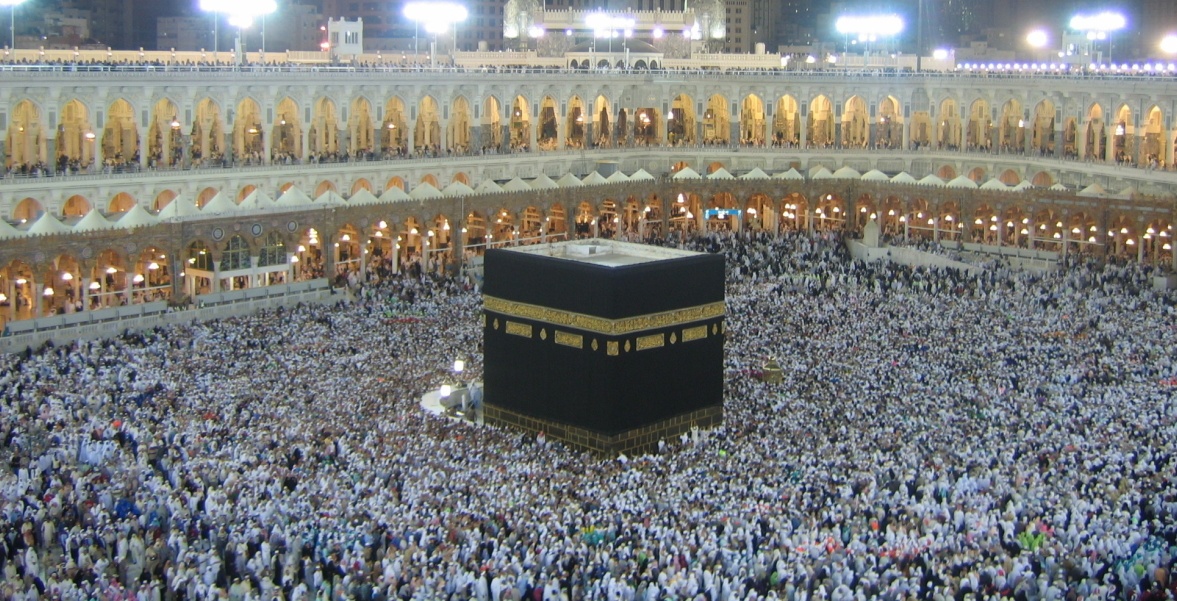

In Christian belief, the Wise Men traveled far to find the Messiah.The Muslim faithful must travel to Mecca. There appears to be an almost irresistible urge in certain cultures for humans Boldly To Go – or at least for some people, usually men, to go.

4 of 5

Stories and examples of heroic travel to unknown places do not exist in some cultures. They instead are told in effect to stay home, to get along with their neighbors, and to mind their own business. The urge boldly to go is found in some humans and cultures, but by no means in all. In those cultures where exploring is deeply rooted in myths, “going boldly” is almost irresistible, while in others with no such, stories, it seems almost impossible to ignite.

5 of 5

Astronautics—the technology of exploring space—is unique among all the sciences because it originated in art and literature. Long before engineers and scientists took the possibility of spaceflight seriously, virtually all of its aspects were explored by artists and writers. And long before the scientists themselves were taken seriously, the arts kept the torch of interest burning.

Astronomy in the Ancient Times

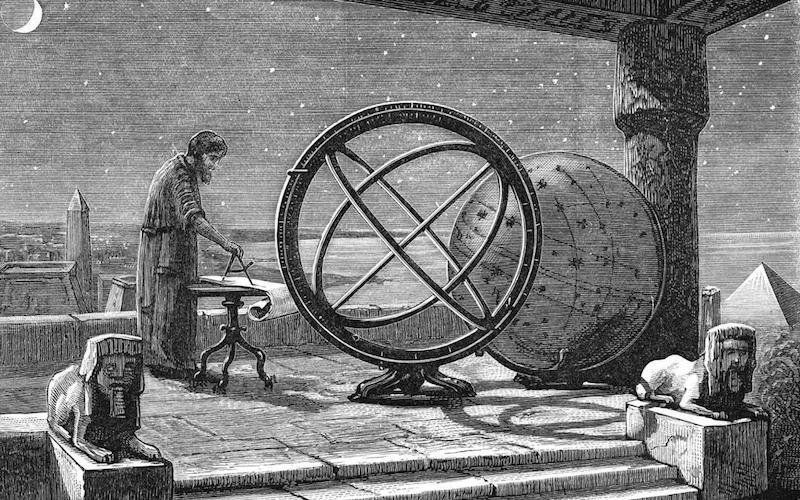

Astronomy is a science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. Humanity has studied astronomy since ancient times. Astronomy, as an orderly pursuit of knowledge about the heavenly bodies and the universe, did not begin in one moment at some particular epoch in a single society. Every ancient society had its own concept of the universe (cosmology) and of humanity's relationship to the universe. In most cases, these concepts were...

Astronomy in the Modern Times

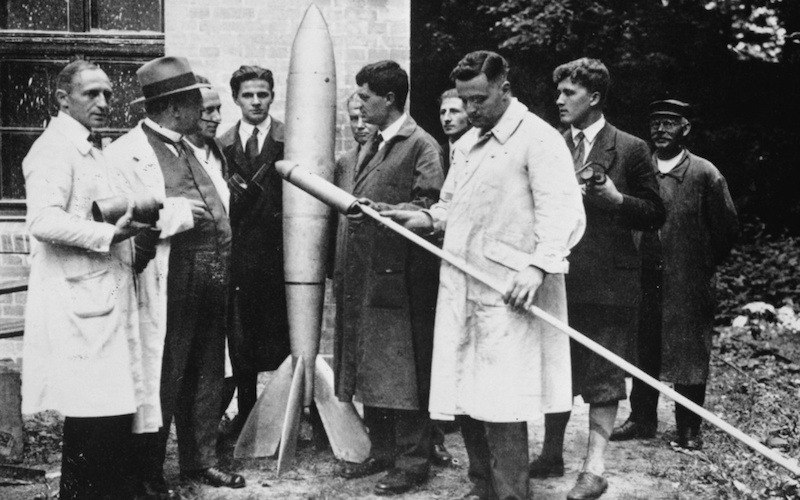

History of Rockets

Space Race

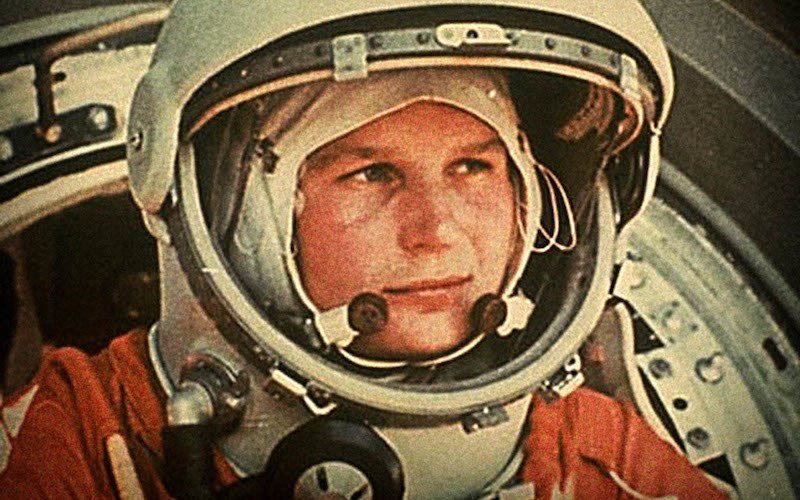

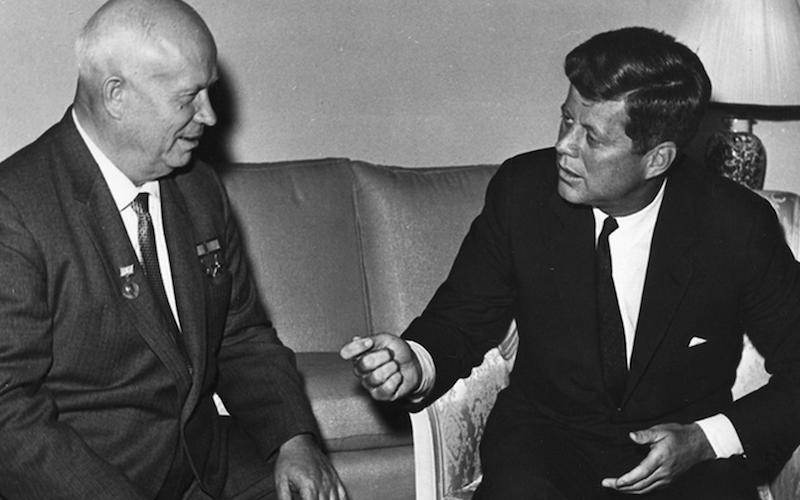

Space exploration and the Cold War

Space Agencies

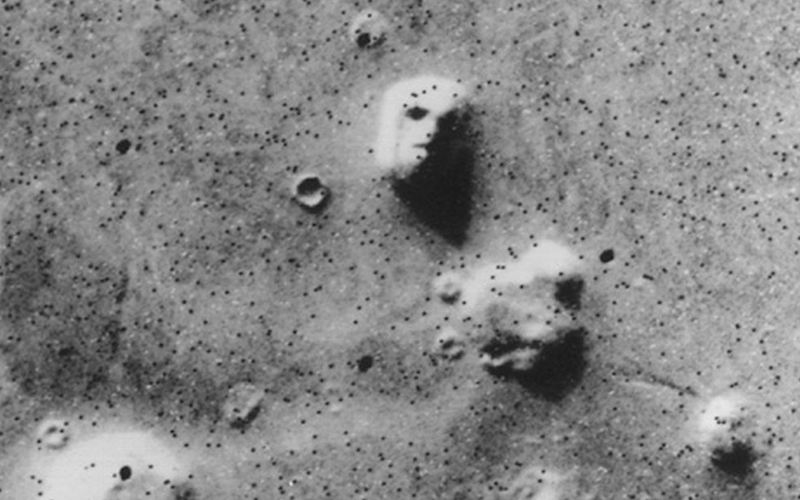

Exploration of Mars

Exploration of the inner solar system

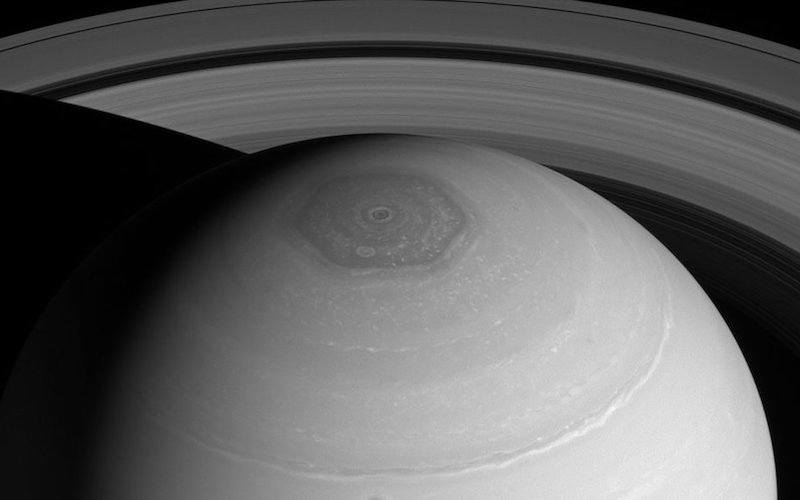

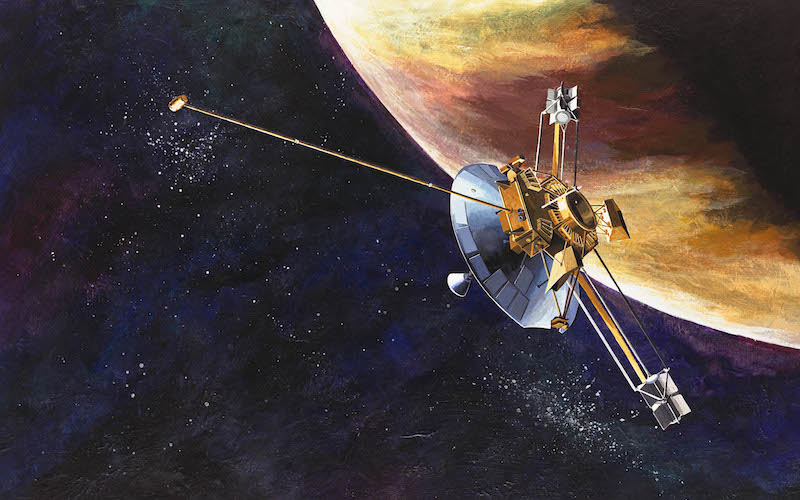

Exploration of the outer solar system

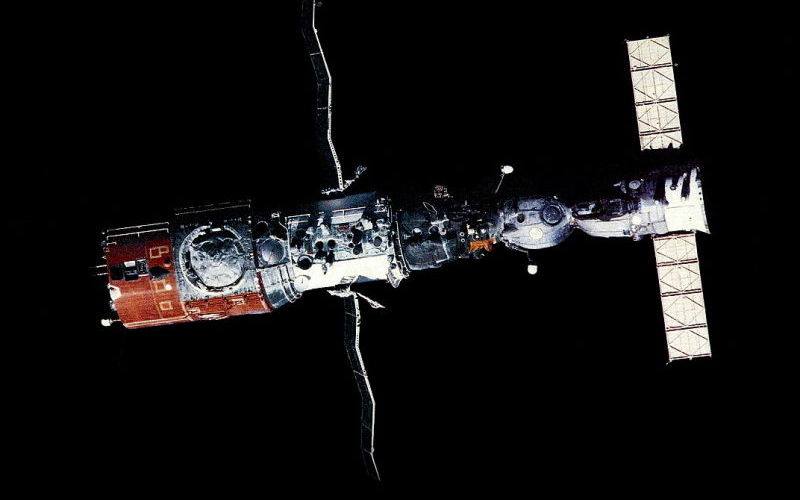

Modern orbital space exploration

History of Satellites

One of the most dramatic moments of the twentieth century occurred on October 4, 1957. The Soviet Union sent a small shiny sphere with four long antennas into space. They called it Sputnik I. Sputnik is a Russian word that means “traveling companion.” The satellite traveled so fast that its ballistic flight continued all the way around Earth.

The Future of Space Exploration

While the current lunar exploration initiative has been justified as a “stepping stone” toward Mars, human missions to Mars represent a major step up in complexity, scale, and rigour compared to lunar missions.

- Cynthia Phillips, Shana Priwer, Space exploration for dummies, Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana, 2009

- James A. Dator, Social foundations of human space exploration, Springer Science+Business Media,New York, 2012

- Ron Miller, Space exploration, Space innovations, Twenty-First Century Books, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2008

- Samuel Willard Crompton, Sputnik/Explorer : The race to conquer space, Chelsea House Publishing, New York, 2007