1915 Spring Offensives

Entente forces attack the German Army

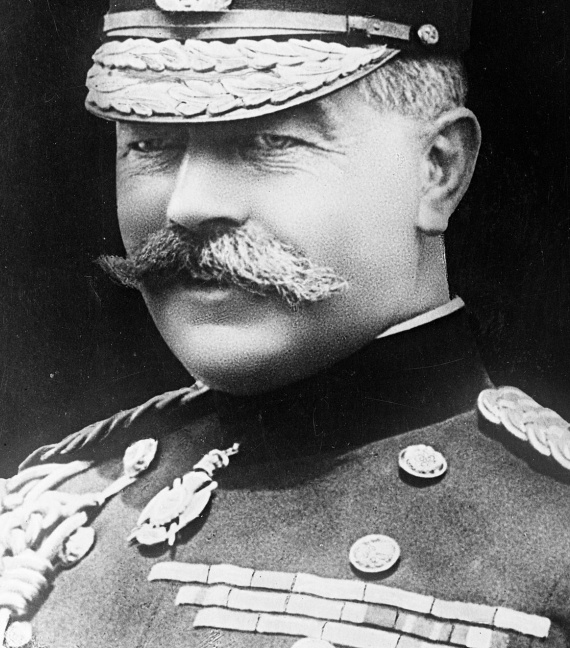

After the winter and early spring battles on the Western Front, French General Joseph Joffre was determined to launch another great offensive. He was confident that France had learned the lessons of the earlier winter offensives. He sought to take advantage of the German reduction in strength on the Western Front while at the same time alleviating pressure on the Russians and the Serbs.

1 of 6

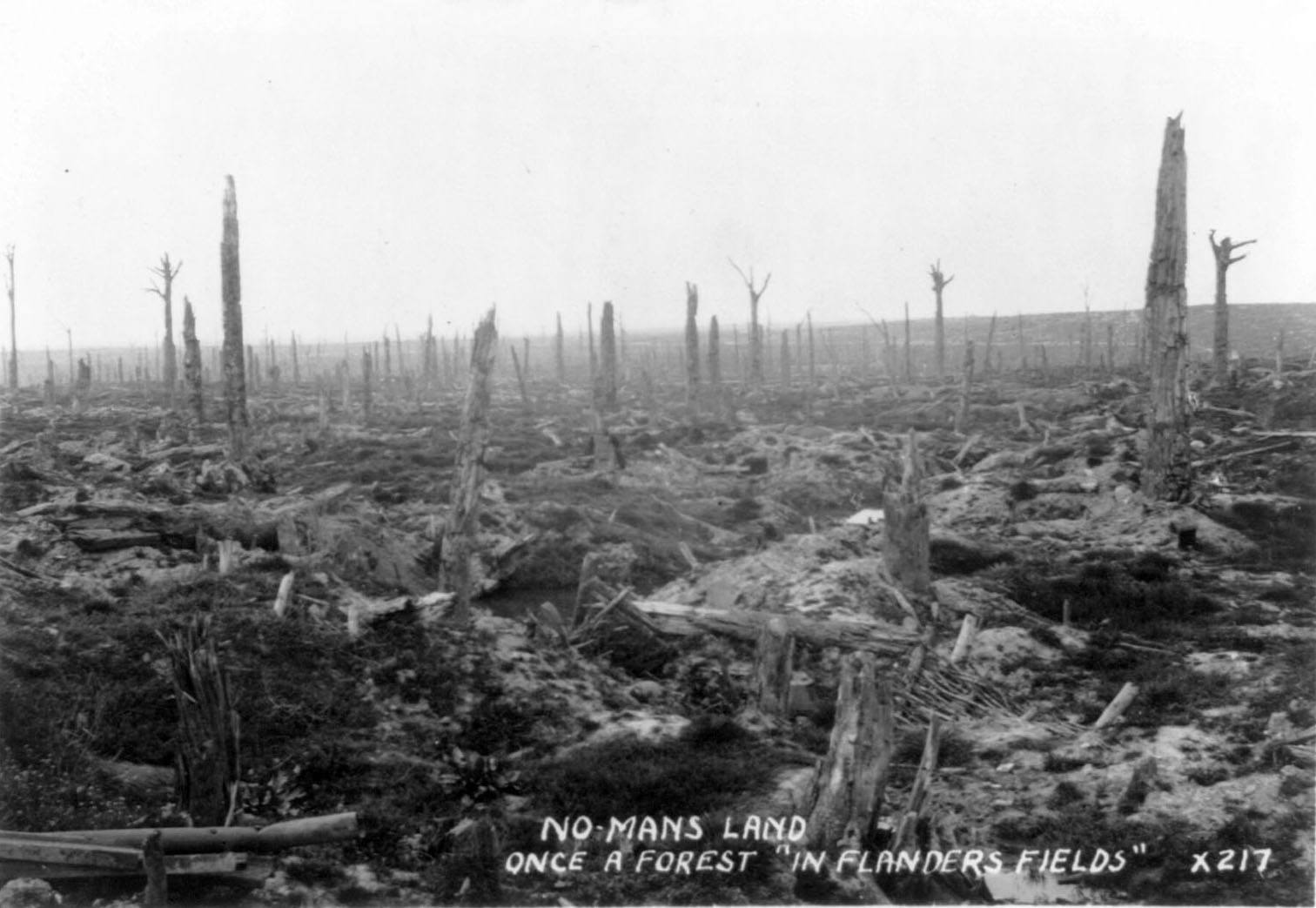

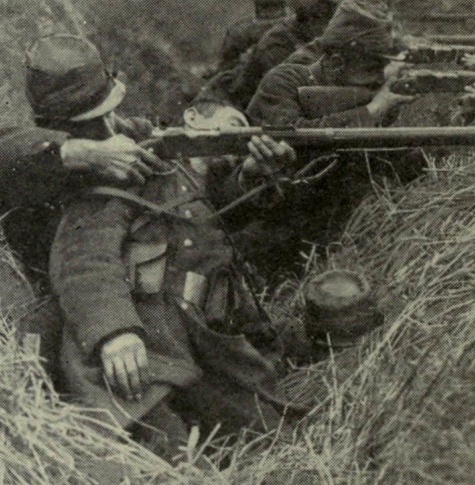

Trenches were being strengthened to resist artillery bombardments, with special well-protected machine gun posts carefully sited to attain the best possible sweeping fire across No Man’s Land. Meanwhile, ever thicker belts of barbed wire were built for attackers to contend with. This was not a single learning curve; no simplistic story here of unremitting progress as one side mastered the problems of trench warfare and moved seamlessly towards victory. Thus a tactic that seemed to work well one month might result in disaster just a few weeks later.

2 of 6

Events on the Eastern Front, where the Central Powers had launched a devastating offensive between Gorlice and Tarnow, made the projected Allied spring offensive in Artois even more significant as a means of giving indirect help to the Russians.

3 of 6

Even when no big offensives were in prospect, the Western Front was by no means quiet. In April the French made an abortive attempt to eradicate the potential threat posed to the eastern flank of Verdun by the German-held St. Mihiel salient, incurring 64,000 casualties in the process.

4 of 6

Although the French had artillery and ammunition available in large quantities while the British did not, the difference between their achievements was negligible.

5 of 6

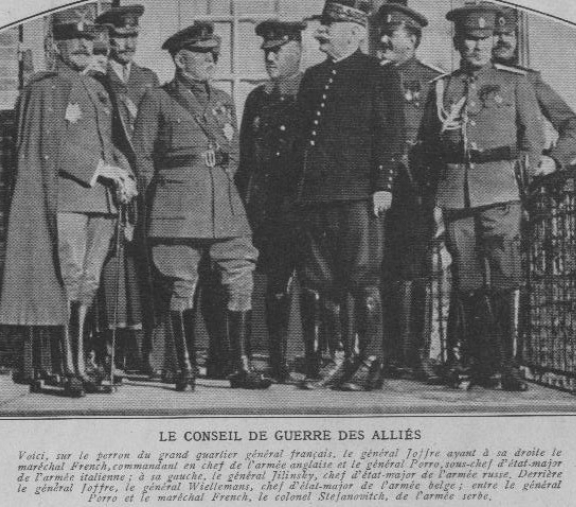

At the first interallied conference of the war, held at Chantilly, the French, British, Belgians, Serbs, Russians and Italians, who had joined the alliance, pledged themselves to common action.

6 of 6

The BEF's part in the offensive operations was a larger-scale version of its own March assault, with Douglas Haig's First Army attacking either side of Neuve Chapelle in a fresh effort to secure Aubers Ridge. The success of the short bombardment in March was borne in mind, but the BEF's worrying shortage of heavy guns and ammunition limited the preliminary bombardment to 45 minutes.

In 1915 Entente strategy had an ad hoc quality. The Western Front represented an irreducible minimum. That was particularly the case for France. The British seemed to still have a measure of choice. Some Liberals, particularly Reginald McKenna, held to the notion that Britain’s primary contribution should be naval and economic: it should be the arsenal and financier of the Entente. Herbert Kitchener suggested Britain should delay its major effort until 1917 so as to allow further attrition of the German Army. But the reality was that Britain was closely linked to the actions of its allies, particularly France: it could not afford to wait.

1 of 5

McKenna argued that British manpower would be best used if it sustained home production and thus ensured the flow of exports that would fund Britain’s international credit and its ability to buy arms overseas and supply them to its allies. But McKenna’s hopes were ill founded. Many of the men McKenna wanted on the factory floor were needed by the army, and the produce of those that remained went to equip that army, not to support Britain’s overseas balance of trade.

2 of 5

When Kitchener was appointed secretary of state for war, he set about the creation of a mass army for deployment on the continent of Europe. By July 1915 the War Office was talking of seventy divisions, a tenfold increase on the army’s size a year before. Although originally raised through voluntary enlistment, such an army could be kept up to strength only by conscription. The retreat of the Russian armies in the summer of 1915 and the defeat at Gallipoli confirmed that Kitchener’s notion of choice was as illusory as McKenna’s. The Russians now had even greater need of British munitions, but they were also desperate for direct military support from the west to draw off the Germans.

3 of 5

In France, Joffre faced hardening political opposition. By sacking the most republican of his army commanders, General Maurice Sarrail, for perfectly proper military reasons, he provided a focus for the left’s criticisms of the army’s independence of political control. The government of René Viviani came under threat, and with it French national cohesion.

4 of 5

Britain feared the upshot of a domestic political crisis in France. Their worst nightmares embraced a government under Joseph Caillaux and the possibility that he might seek an accommodation with Germany. Kitchener reversed his views of Britain’s role on the western front: he told Haig that ‘we must act with all our energy, and do our utmost to help the French, even though by so doing, we suffer very heavy losses indeed’. Thus, as the Central Powers began to pull apart, those of the Entente converged.

5 of 5

As far as strategy and tactics went, the choices were simple. Joffre and the French General Staff, like their British colleagues, had only one concept of attack: the coup de bélier, the massive blow of the battering ram, which would break the front open and run the Germans out of France.

The First Winter

During the first winter of the war, after heavy fighting in the previous months, the front stabilized. A series of trenches and fortifications were built by both sides all along the front. During this time the French launched a series of attacks against German positions, attacks which would ultimately prove to be costly in terms of casualties and tactically indecisive. A curious anomaly happened in some sections of the front during...

Battle of Neuve Chapelle

At the battle of Neuve Chapelle the British mounted an offensive against the German in the Artois region of France.

Second Battle of Ypres

During the Second Battle of Ypres the German Army launched a series of attacks against the Entente forces in and around the Belgian town of Ypres. The battle marked the first time the German army used poison gas on the Western Front. In the end, the Entente forces managed to resist the German attacks.

1915 Autumn offensives

During the autumn of 1915 the French and British organized a series of new offensives against the German army designed to break the German lines. However, because they lacked sufficient artillery ammunition and could not move the reinforcements quickly enough these offensives were doomed to failure, especially when considering the well organized German defense.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998