The First Winter

Events on the Western Front during the winter of 1914 - 1915

By the end of the First Battle of Ypres, both the German and Entente forces were exhausted from heavy fighting and suffered from a shortage of ammunition and low morale. The combatants tried to consolidate their trenches as much as the winter weather and lack of supplies allowed. In December both sides tried exploratory attacks, often designed to straighten the line or to secure a tactically significant position, but to little real effect.

1 of 7

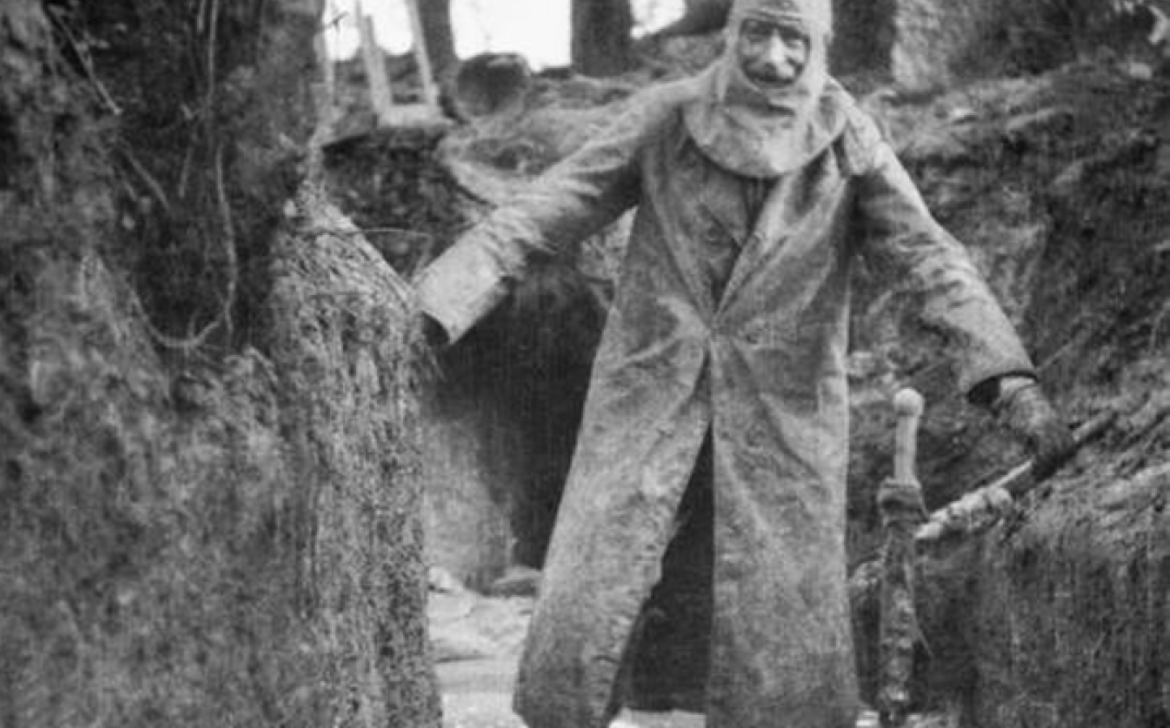

Christmas 1914 was marked by a spontaneous unofficial truce in Flanders, where German, French and British soldiers fraternized in No Man's Land, taking photographs, swapping souvenirs and even playing football. There was no real desire for compromise or negotiation: the Christmas Truce was an exercise in sentimentality and nothing more. As the war became increasingly bloody and impersonal, hardening attitudes ensured that such incidents on this scale would not recur.

2 of 7

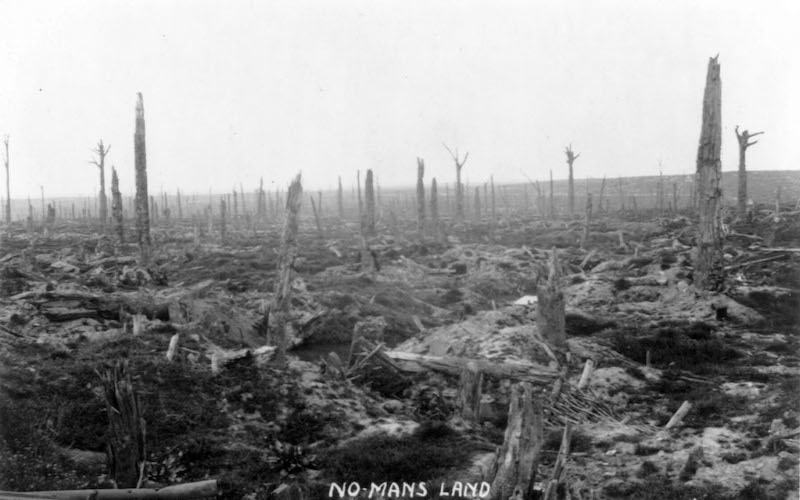

Although by no means safe, the trenches enabled the troops to avoid the worst effects of artillery, machine gun and rifle fire. Only high explosives and shells from high-angle weapons dropped directly into the trenches posed a pressing danger. One thing was certain: a defending garrison tucked below ground level behind a tangle of barbed wire could deploy bolt action rifles and heavy machine guns to deadly effect against troops attempting to cross No Man’s Land. Anyone caught in the open was horribly vulnerable to artillery fire, so any attack was an intimidating prospect.

3 of 7

One improvement for the French soldiers was the gradual issue of new horizon blue uniforms gradually through the course of 1915. This was of course a massive undertaking and for a while the French soldiers presented an unprepossessing appearance in a bizarre mixture of old and new, although at least the light blue uniforms were less visible where it counted – on the battlefield.

4 of 7

By December 1914 there were major operations underway in five separate sections of the front, some of these overlapping with others begun in 1915. As a result there were always at least two and usually three French offensives going on in different sections of the front, while the Germans, usually regarded as passively defending their lines during this period, mounted half a dozen major operations as well. Any narrative of the fighting, therefore, ends up doing some violence to the chronology.

5 of 7

With the onset of winter, the deadlock became total. Continuous trench lines now extended from the Belgian coast to the Swiss frontier. The Germans had not yet constructed the formidable defensive systems which, for most of the war, their overall strategy in the west would dictate. Believing, in late 1914, that the building of a second position might weaken the resolve of troops in the front defences, the Germans depended at first on a single line, to be held at all costs. However, during the winter they revised this policy, adding depth to these defences with concrete machine-gun posts to the rear of the front line.

6 of 7

The Germans, whose decision to retreat from the Marne to ground of their own choosing allowed them to avoid the wet, low-lying,

overlooked sectors they left to their enemies, were better established. Theirs had been a deliberate strategy of entrenchment, as reported by the commanders of the pursuing French formations which were stopped in sequence as they advanced from the Marne.

7 of 7

The Winter Battle in Champagne dragged on, with long pauses, until spring, costing the French 100,000 casualties and bringing them no gain in territory at all. There was also local and quite inconclusive fighting further south, in the Argonne, near Verdun, in the St. Mihiel salient, and around Hartmannsweilerkopf in the Vosges, a dominant point to which both sides sent their specialized mountain troops.

For the Germans, 1915 was a year of war that should not have been: their whole strategy had been based on a quick war. Now they found themselves embroiled in a two-front war, with two enemies – France and Russia – fully mobilized and another – Britain – slowly amassing her strength and standing relatively invulnerable behind her navy. The Chief of General Staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn, faced a grim situation.

1 of 7

‘As a result of the unfortunately widespread catchword “the war must be won in the East,” even people in high leading circles inclined to the opinion that it would be possible for the Central Powers actually “to force Russia to her knees” by force of arms, and by this success to induce the Western Powers to change their mind. This argument paid no heed either to the true character of the struggle for existence, in the most exact sense of the word, in which our enemies were engaged no less than we, nor to their strength of will. It was a grave mistake to believe that our Western enemies would give way, if and because Russia was beaten. No decision in the East, even though it were as thorough as was possible to imagine, could spare us from fighting to a conclusion in the West. For this Germany had to be prepared at all costs.’ (Erich von Falkenhayn)

2 of 7

Falkenhayn’s personal preference was for a negotiated peace with one of Germany’s adversaries – preferably Russia – allowing Germany to concentrate on beating first France and then Britain – whom he had come to see as the ultimate enemy. There was a great deal of dissent in the German High Command, with an opposing school of thought rapidly coalescing around Generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff who were far more confident that outright victory could be achieved over Russia in 1915.

3 of 7

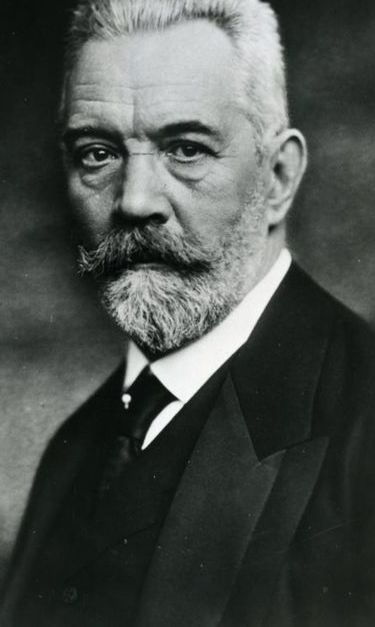

Falkenhayn lacked the authority to enforce his will; indeed, there were widespread conspiracies against him across the German military and political hierarchy, involving the Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, Hindenburg – who sought the position of Chief of General Staff for himself – and the somewhat resentful Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. With the firm support of the Kaiser, Falkenhayn remained in post, but he was somewhat weakened in the process and was forced to send part of his reserves to the Eastern Front: this was a victory without power.

4 of 7

Austria-Hungary appealed for help after a series of terrible reverses against the Russians and Serbs left her teetering on the brink of military collapse. There were also rumbling noises emanating from Italy and Romania; it seemed that, rather than join the Central Powers as had been hoped, they were far more likely to join the Entente. This could only add to the pressure on Austria-Hungary. This combination of circumstances left Falkenhayn with no choice: he began to send his precious reserves to the Eastern Front, intent at first on stabilizing Germany’s faltering ally, then on making her secure from any future attack.

5 of 7

Having prepared for siege operations at the outset of the war, the Germans were comparatively well endowed with weapons suitable for trench warfare, including mortars, grenades, heavy guns and howitzers.

6 of 7

Falkenhayn's decision to stand temporarily on the defensive in the west – where he believed the war would ultimately be won – proved a huge mistake. A weakened and now inexperienced BEF might not have withstood further heavy blows during the winter. But the respite granted by the Germans allowed the Entente to reorganize, giving Britain, in particular, the chance to train Kitchener's New Armies and strengthen the BEF with additional Territorial and Dominion contingents.

7 of 7

Hindenburg and Ludendorff could claim that all the titanic efforts in the west had resulted only in deadlock, whereas they – with fewer resources – had twice frustrated Russian attempts to invade Germany and had also won territory in Russian Poland. Since both the Kaiser and his Chancellor, Bethmann-Hollweg, agreed that the Eastern Front should be given priority, Falkenhayn found it necessary to stifle his own immediate strategic inclinations.

Battle of Neuve Chapelle

At the battle of Neuve Chapelle the British mounted an offensive against the German in the Artois region of France.

1915 Spring Offensives

During the spring and summer of 1915 the Entente forces, under the command of French General Joseph Joffre, launched a series of attacks against the German lines. These attacks would ultimately prove costly failures in terms of human lives, while failing to capture any significant portion of the front from German hands.

Second Battle of Ypres

During the Second Battle of Ypres the German Army launched a series of attacks against the Entente forces in and around the Belgian town of Ypres. The battle marked the first time the German army used poison gas on the Western Front. In the end, the Entente forces managed to resist the German attacks.

1915 Autumn offensives

During the autumn of 1915 the French and British organized a series of new offensives against the German army designed to break the German lines. However, because they lacked sufficient artillery ammunition and could not move the reinforcements quickly enough these offensives were doomed to failure, especially when considering the well organized German defense.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998