1915 Autumn offensives

The Entente tries to break through the German lines

After the French and British forces tried and failed to break through the German lines in the spring, they sought to organize a series of new offensives with the same goal in mind. Using a variety of tactics, depending on the battlefield, they tried to break the deadlock on the Western Front of World War 1. While none of the approaches was wrong per se, they did not offer a coherent solution to the problems of waging a successful offensive in the conditions on the Western Front. Week by week the German lines became stronger, with more trenches and barbed wire, and with the advent of deeper dugouts, concrete fortifications and self-contained redoubts.

1 of 6

In planning for his autumn offensives, General Joseph Joffre tweaked his operational ideas to reflect what had been learned in the earlier campaigns. The lessons were by no means clear. There was wide disagreement within the French High Command as to the best way to proceed. Joffre now sought, not an easily plugged breakthrough on a narrow front, but a wide-ranging series of mutually supporting major offensives to promote confusion in the German High Command, prevent the concentrated deployment of German reserves and precipitate a wholesale rupture of the lines at the decisive point.

2 of 6

Joffre warned of the dangers of allowing the Germans to pick off one power at a time: ‘An energetic combined offensive, involving all the allied armies other than the Russian, is the only means of warding off this danger and of beating the enemy.’ Attacking on the Western Front was vital not just for strategic reasons: if on the defensive, he argued, ‘our troops will little by little lose their physical and moral qualities.’

3 of 6

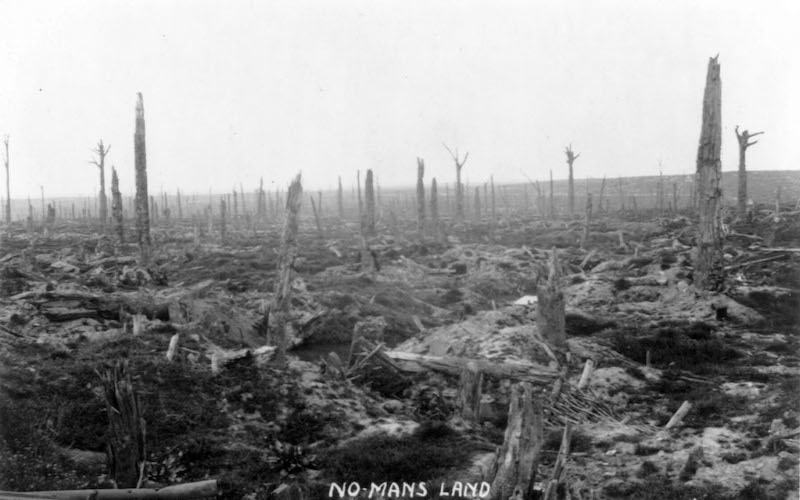

The great Artois and Champagne Offensives were both ignominiously closed down, achieving nothing but more casualties. The battlefields of Champagne had become places of dread to the French troops, as its desolate landscape bleached of hope sucked them in and surrounded them.

4 of 6

To deliver the principal blow in the more thinly populated Champagne region, the French had to construct additional light railways and roads, causing the postponement of the offensive. The Germans, however, were not idle and hastened to build a new second defensive position behind the first. They employed prisoners of war and French civilians to speed up the work.

5 of 6

Both British and French generals were agreed that the breakthrough would be achieved not by the first wave of troops, who would break into the enemy front line, but by the second. Traditional notions of generalship dictated that the reserve should be in the hands of the supreme commander, who would decide when to commit it in the light of the overall situation. But the delays in communication and in getting forward over a shelled and fractured battlefield in muddy weather argued that control of the reserves – and therefore command authority – should be delegated.

6 of 6

The year 1915 came to a gloomy close with the failure of the grand French offensives in Champagne and Artois, the collapse of Serbia, and bad news from the Balkans and the Eastern Front. The only concrete achievement was a string of government press releases alleging the recapture of obscure pieces of French real estate such as Hartmannswillerkopf, Les Éparges, and the Vauquois, together with a few hectares of meaningless ground in the Champagne and Artois.

After an analysis of the options by his staff, Joseph Joffre decided to launch the offensives in the Artois and Champagne. The lure of the Vimy Ridge in Artois and the railway junctions tucked just behind the German lines at Mézières in the Champagne region was as strong as ever. This time the main attack would be carried out by the Fourth Army in Champagne, with significant ‘secondary’ attacks to be launched on the same day by the Tenth Army in the Artois and by the British First Army at Loos. Ultimately, Joffre had his eye on the Artois and Champagne offensives squeezing out the so-called Noyon Salient pointing towards Paris.

1 of 4

General Ferdinand Foch favored more restrained processes of methodical attack, somewhat similar in concept to ‘bite and hold’, consisting of a series of carefully planned and prepared steps, delineated by the range of the field artillery batteries.

2 of 4

The far less senior, but increasingly highly respected Philippe Pétain saw the war in terms of attrition. For him, victory would belong to the last man standing. As such he advocated a largely defensive strategy designed to conserve manpower with only limited well-prepared attacks to avoid excessive losses.

3 of 4

Joffre had his own answer to the augmented German defences: to blast them from the face of the earth. He demanded ever more heavy artillery, with the intention of achieving a rough parity of numbers with his field artillery. As a result, by the summer of 1915 the French had thousands of artillery pieces. These were intended to act like an old fashioned battering ram in the new version of siege warfare.

4 of 4

The president of the French Republic, Raymond Poincaré, was among those opposed to further offensives. But the eventual British support gave Joffre the leverage over his political masters that he needed in order to go ahead.

The First Winter

During the first winter of the war, after heavy fighting in the previous months, the front stabilized. A series of trenches and fortifications were built by both sides all along the front. During this time the French launched a series of attacks against German positions, attacks which would ultimately prove to be costly in terms of casualties and tactically indecisive. A curious anomaly happened in some sections of the front during...

Battle of Neuve Chapelle

At the battle of Neuve Chapelle the British mounted an offensive against the German in the Artois region of France.

1915 Spring Offensives

During the spring and summer of 1915 the Entente forces, under the command of French General Joseph Joffre, launched a series of attacks against the German lines. These attacks would ultimately prove costly failures in terms of human lives, while failing to capture any significant portion of the front from German hands.

Second Battle of Ypres

During the Second Battle of Ypres the German Army launched a series of attacks against the Entente forces in and around the Belgian town of Ypres. The battle marked the first time the German army used poison gas on the Western Front. In the end, the Entente forces managed to resist the German attacks.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003