Battle of Neuve Chapelle

First major British offensive of the Great War

10 - 13 March 1915

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle was a conflict on the Western Front of World War One. The battle was a British offensive in the Artois region of France. The British managed to break through at Neuve-Chapelle but the success could not be exploited. Simultaneously there was a planned French attack at Vimy Ridge on the Artois plateau, to threaten the German Army from the south as the British attacked from the north. The French attack was cancelled when the British were unable to relieve the French 9th Corps, which was intended to take part in the attack. After a costly German failed counterattack, the British consolidated the ground that had already been won and cancelled any further attacks.

1 of 5

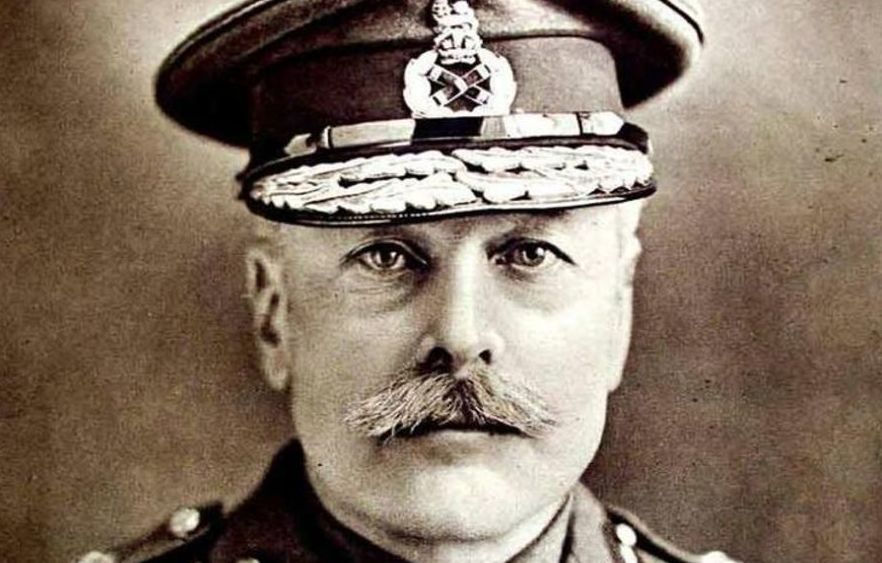

The French had gained a poor opinion of the British Expeditionary Force during the 1914 campaign, only alleviated by its late-flowering demonstration of determination during the First Battle of Ypres. The Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the first major BEF attack on German entrenched positions, would be conducted by the First Army, composed of the IV Corps and Indian Corps, under the command of General Sir Douglas Haig.

2 of 5

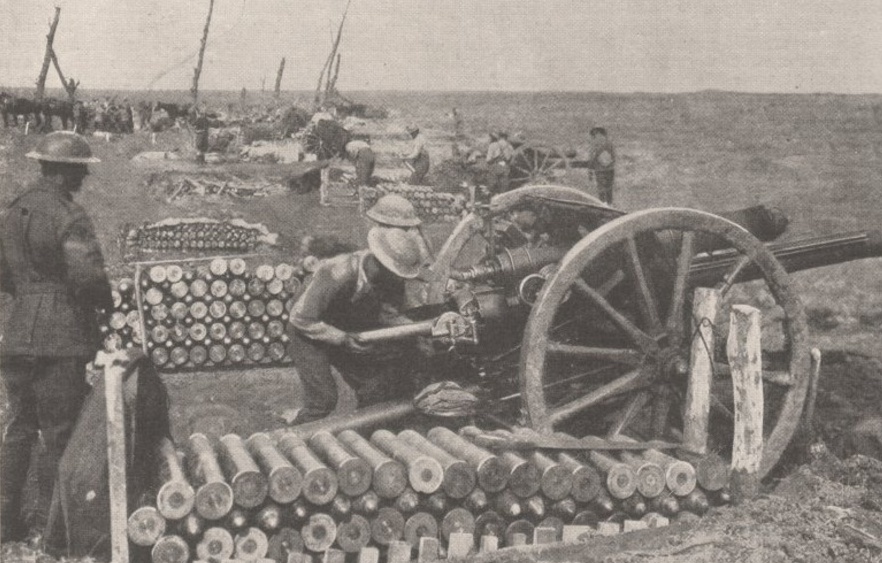

As the artillery only had sufficient ammunition for three or four days of serious operations, contingency plans were also prepared for taking up defensive positions, depending on the degree of success of the whole operation.

3 of 5

The BEF, after a wretched winter in the trenches, was in no state to support the French offensives until the early spring of 1915. However, knowing that the War Council in London was considering operations in the Dardanelles and Balkans, its senior commanders feared that unless the BEF made a positive contribution soon, resources might be diverted away from the Western Front.

4 of 5

The appointment of Lieutenant-General Sir William Robertson as the BEF Chief of Staff also brought a more robust approach to the work of General Headquarters (GHQ). A plan was approved for an attack on a narrow front in Flanders. The aim was to eliminate the German salient around Neuve-Chapelle, secure Aubers Ridge and threaten Lille, an important road and rail junction.

5 of 5

Neuve Chapelle was launched partly because Sir John French was unable to comply with General Joseph Joffre's request that the BEF assist the preparation of the coming Artois offensive by taking over more of the French line, and partly because the Field Marshal was anxious to restore his army's reputation, damaged in French eyes by its failure to win ground during the December fighting.

Still doubtful of British capacity to undertake an offensive, French General Joseph Joffre’s initial priority for the BEF in 1915 was to get his British allies to accept a greater share of the front line, stretching from the Ypres Salient down to the La Bassée area. This would allow the French to release more troops for their own offensives. Although the BEF was grossly tardy in taking over more of the line, the British commander, Sir John French, proved surprisingly willing to launch a supporting attack in what would ultimately be the Battle of Neuve Chapelle.

1 of 6

It is well worth examining the stages in which the different components of the BEF were added to the plans of the generals in their early attempts to crack the problem of a successful offensive. The first part was obvious: infantry were ever-present. The tactics were essentially those of fire and movement, an approach frequently decried as old-fashioned, with scornful reference to ‘Boer War tactics’. Yet what else could it have been based on? It was far too soon to properly digest the lessons of 1914.

2 of 6

The role of cavalry had been deeply controversial before the war. A strange dispute arose between those promulgating pure cavalry reliant on shock and awe and those in favor of mounted infantry. Although the cavalry had been invaluable in 1914 both for reconnaissance in open warfare and to plug gaps in an emergency, afterwards they became very much an afterthought – a force to be used when the battle was all but done, to try to maximize the spoils of victory. In the absence of any other fast moving strike force, it was the cavalry or nothing when it came to rapid exploitation.

3 of 6

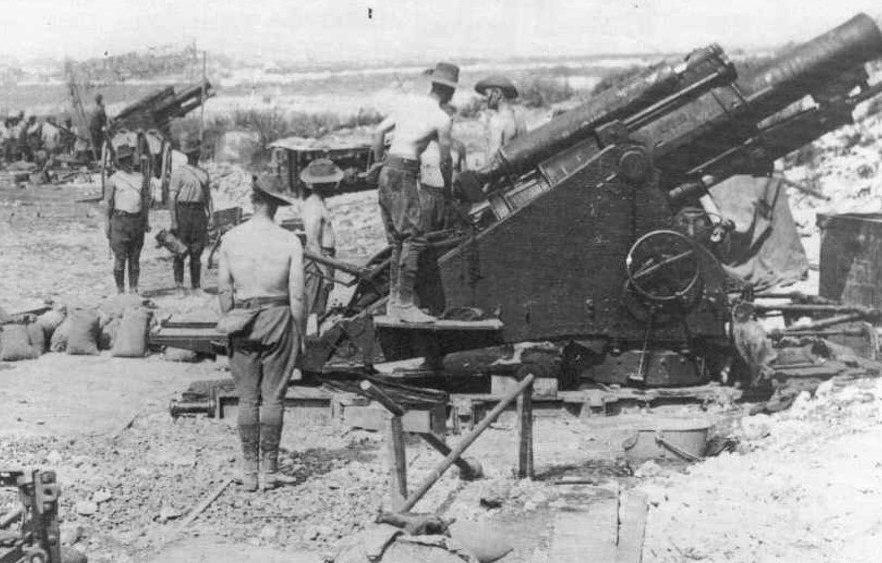

The Royal Artillery had gone to war with little grasp of its role in combat. It was thought the gunners’ task was to shower the opposing infantry with shrapnel shells spraying out deadly steel balls. When batteries were deployed in a defensive role in support of the infantry, it was not yet understood that this did not mean that the actual guns had to be sited close to the infantry their shells were defending. Positioned within a few hundred yards of the infantry, many gunners were soon dispatched by the German artillery or infantry.

4 of 6

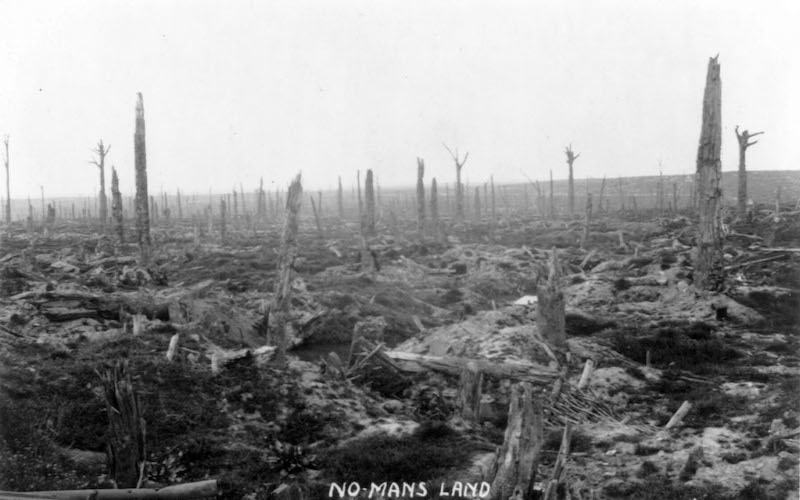

When the British artillery guns were covering an attack there was also no concept of suppressing the ability of the German infantry and artillery to fire on British troops while they were vulnerable in No Man’s Land; early in the war it was destruction or nothing – yet there was a shortage of the high explosive shells that would make destruction feasible. And of course the Royal Artillery was simply too small: it lacked the thousands of guns, the trained gunners, the techniques, the tactical sophistication and the almost unlimited supplies of munitions necessary to dominate the modern battlefield. It would take years to remedy these stark deficiencies.

5 of 6

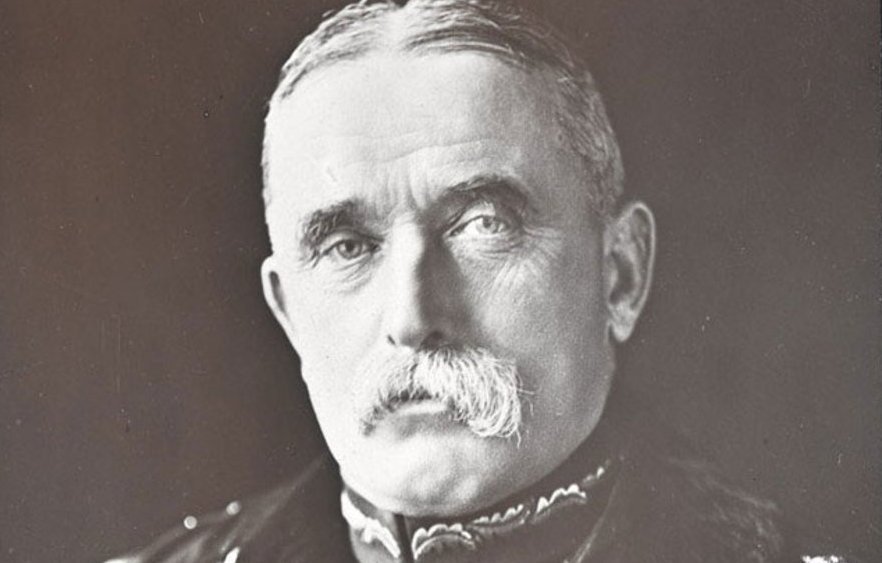

Haig’s overall plans called for converging attacks by IV Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Henry Rawlinson, and the Indian Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Sir James Willcocks, supported by massed artillery, to seize the village before taking up defensive positions. Success would trigger further attacks on either side of the breakthrough intended to widen the gap and then push toward the Aubers Ridge. This in turn offered the possibility of disrupting German communications to Lille.

6 of 6

The dispatch of the Regular 29th Division to the Dardanelles prevented the BEF from relieving the French IX Corps at Ypres and

precluded a simultaneous French attack in Artois. Sir John French decided that the BEF would carry on regardless. The British Commander in Chief was determined to dispel the prevailing view among his French allies that the BEF was incapable of launching an effective offensive action.

The First Winter

During the first winter of the war, after heavy fighting in the previous months, the front stabilized. A series of trenches and fortifications were built by both sides all along the front. During this time the French launched a series of attacks against German positions, attacks which would ultimately prove to be costly in terms of casualties and tactically indecisive. A curious anomaly happened in some sections of the front during...

1915 Spring Offensives

During the spring and summer of 1915 the Entente forces, under the command of French General Joseph Joffre, launched a series of attacks against the German lines. These attacks would ultimately prove costly failures in terms of human lives, while failing to capture any significant portion of the front from German hands.

Second Battle of Ypres

During the Second Battle of Ypres the German Army launched a series of attacks against the Entente forces in and around the Belgian town of Ypres. The battle marked the first time the German army used poison gas on the Western Front. In the end, the Entente forces managed to resist the German attacks.

1915 Autumn offensives

During the autumn of 1915 the French and British organized a series of new offensives against the German army designed to break the German lines. However, because they lacked sufficient artillery ammunition and could not move the reinforcements quickly enough these offensives were doomed to failure, especially when considering the well organized German defense.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003