Japan's defeat in the Second Sino-Japanese War

Unexpected victory for China

Germany was defeated in May 1945. Preparations immediately began for a final assault on Japan that might involve massive numbers of Chinese troops. Instead, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August forced Japan’s sudden surrender, which took most of the world, including China’s leaders, by surprise.

1 of 3

By the start of 1945 it seemed clear that the Nazi grip on Europe would end within months. Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill turned their attention to concluding the war in Asia as swiftly as possible. At Tehran, in November 1943, Stalin had pledged an eventual Soviet entry into the Pacific War when the European tide had turned, and now Roosevelt wanted to make sure that commitment was acted on.

2 of 3

The idea that war could lead to the rebirth of China proved the great illusion. The Nationalists admitted as much on 3 September 1945, just after the end of the war, when they issued an order that announced ‘this year’s land taxes will be remitted for the whole year in all provinces that fell to the enemy. We depend on the remaining provinces in the rear for military rations and the people’s food needs this year, but their land taxes will be remitted the following year. All military recruitment will be stopped throughout the country from today’. In explaining the measure, the text hailed the defeat of Japan as a great historical achievement. But it also mourned the enormous loss of life and the destruction of property and concluded that ‘although the War of Resistance has now ended, the task of national reconstruction has only just begun’. The hopes expressed at Wuhan in 1938 had not been realized.

3 of 3

The international element of Nationalist strategy never worked out as the Nationalists had hoped. The Nationalists were right in believing that they could not win without outside support. However, while the Soviet Union supported the Nationalists actively until 1939, following the Battle of Nomonhan their involvement was scaled down and ended completely after 1941. Support from the USA and Britain was at best of ambiguous value to the Nationalists, and their interests were consistently subordinated to those of their allies.

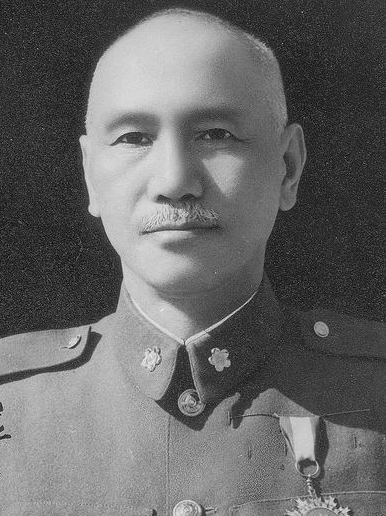

The halting of Japanese forces was something Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek could cling to at the start of 1945, and he also found other grounds for cautious optimism. Chiang took General Joseph Stilwell's recall as a sign that America was 'sincere' about helping China: 'This is the greatest comfort for me in the new year.' He was still concerned about American attempts to arm militarist rivals such as Xue Yue and Long Yun, but told himself that the American attitude was 'completely different' from the type of imperialism advocated by the British.

1 of 3

Chiang remained convinced that the US was attempting to arm rival militarists, 'distributing weapons as a bait, so the military will worship foreigners and disobey orders'. After his humiliation at Stilwell's hands, Chiang was now ready to be suspicious at the slightest sign of disrespect from his allies.

2 of 3

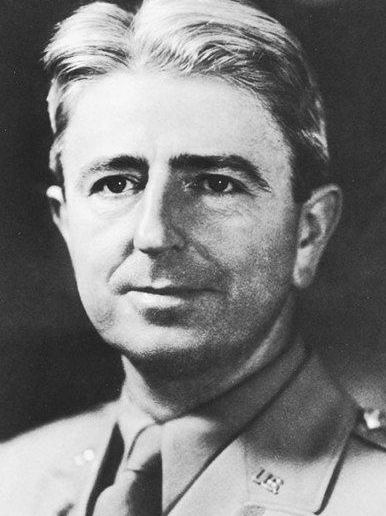

Stilwell had left without waiting to brief his successor, General Albert Wedemeyer, nor had he left behind much in the way of paperwork. Wedemeyer was impressed by Chiang Kai-shek, but shocked by the state of the overall military command in China. Chiang also balked at the discovery that Wedemeyer intended to continue Stilwell's policy of controlling Lend-Lease supplies. 'It's clear US policy hasn't changed at all,' he wrote. 'This makes my heart bitter.'

3 of 3

Chiang was still persuaded that the US wanted to raise China's status in the world, whereas the British had no intention of taking the country seriously in any post-war settlement.

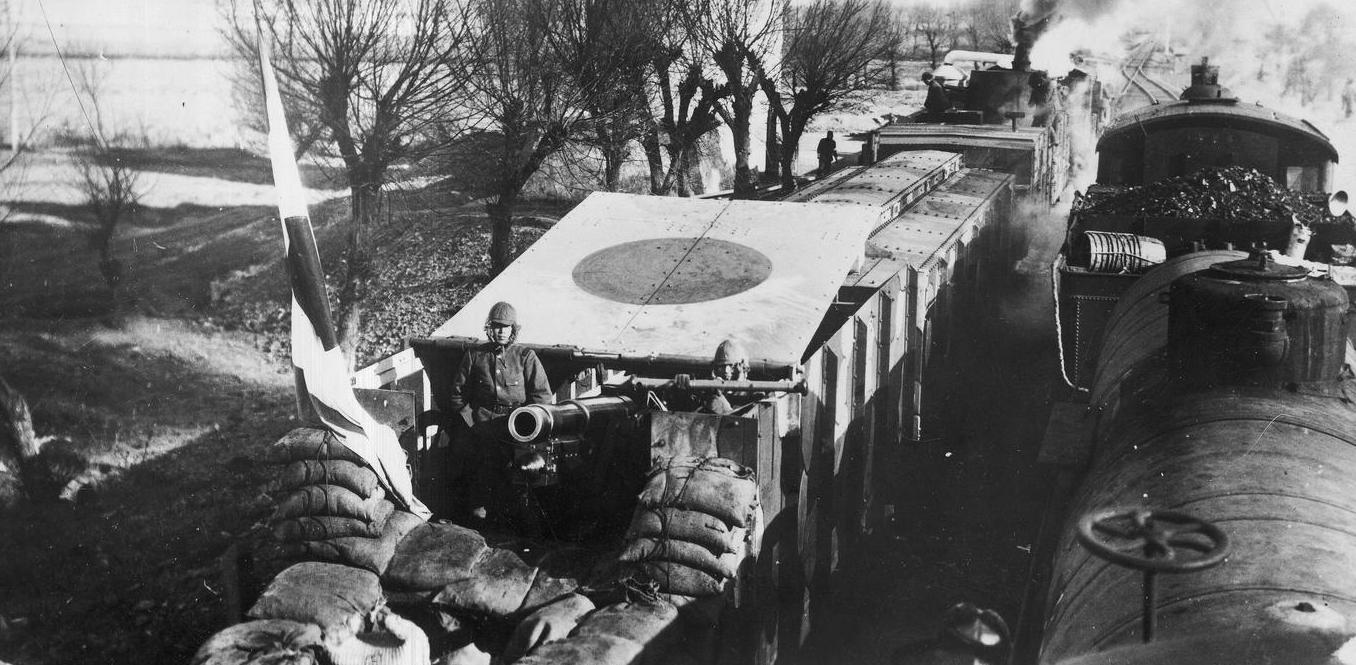

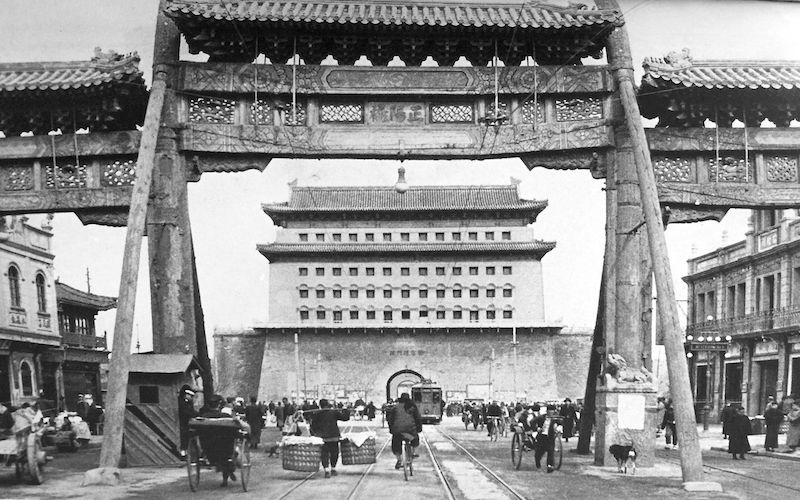

Japanese Invasion of China During the Second Sino-Japanese War

In 1937 what seemed at first a minor border skirmish near Peking quickly escalated into a full scale war between the Chinese and Japanese. The Japanese invasion of China had disastrous consequences for the Chinese: within the next year of fighting major cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Wuhan fell to the Japanese.

Resisting Alone: China’s Defensive War Against Japan

After 1938 the nature of the war in China changed: the gigantic clashes of the first 2 years were fewer in number. As the Chinese started focusing on defensive actions, and guerilla warfare in the occupied areas, the Japanese tried to subdue the locals by staging a number of offensives.

Second Sino-Japanese War: a war of alliance

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, China finally found some much needed allies as the US and British Empire entered the war against Japan. In 1944 Japan launched a massive offensive in China, code named Operation Ichi-go, during which Henan province fell to Japanese troops. However, despite this massive effort, China still did not surrender.

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a war between the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Communists that started in the late 1920's. After the end of the Second World War and Japan's defeat the civil war resumed and the Communists were eventually victorious.

- Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2007

- Peter Zarrow, China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949, Routledge, New York, 2005

- Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival, Allen Lane, London, 2013

- Hans van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China, 1925-1945,Routledge-Curzon, London, 2003