Chinese Civil War

Chinese Communist victory over the Nationalists

1946 - 1950

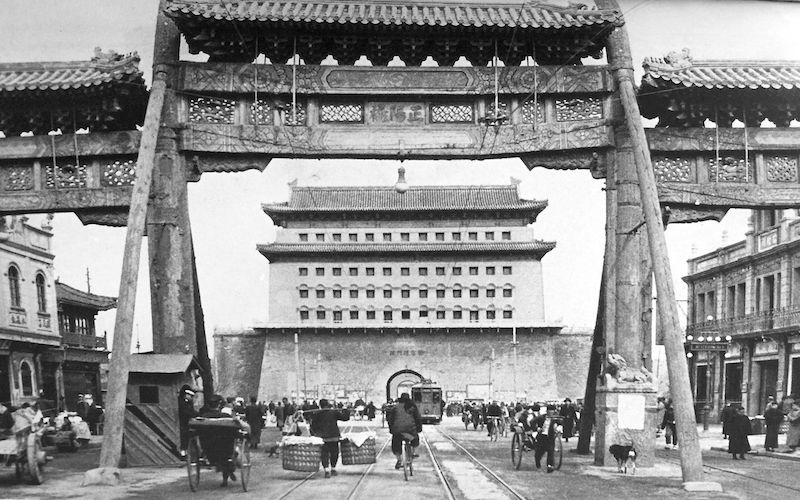

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Nationalists and the Chinese Communists. The conflict initially started in 1927, but a decade later the two sides banded together to defeat the Japanese invasion of China. After the defeat of the Japanese Empire and the end of the Second World War, the civil war resumed between the two Chinese factions. The war ended with a Comunist victory and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. The remaining nationalists, representing the Republic of China, had to retreat to Taiwan.

1 of 4

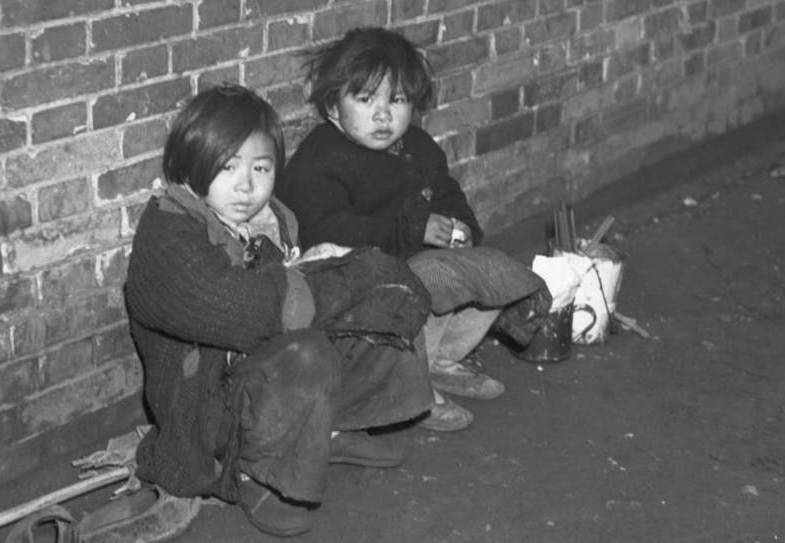

The victory of 1949 marked the Communist accession to national power. The extent of the revolution can be defined by the massive social changes put into effect between 1946 and 1952: the abolition of landlordism and the extermination of the landlord class, the mobilization of the peasantry, and the severe limits placed on capitalists, not to mention the takeover of government by a new Party-military machine that would soon impose new controls over all elements of society. It can also be defined by the ability of the new government – once again in Beijing – to command the resources of the country and the loyalty of its citizens.

2 of 4

The civil war between 1946 and 1949 that finally brought the Communists to power was hard-fought, and the final outcome was by no means preordained. In hindsight, one can see the fundamental strengths of the Communist military machine and government-in-waiting. The Nationalist weaknesses were laid bare by defeat – although they were obvious enough at the time and provoked US doubts about its ally.

3 of 4

Intellectuals and urban populations did not turn to the Communists en masse, but inevitably, as the power-holders, the Nationalists received the lion’s share of the blame. Civil war was far more demoralizing than the anti-Japan war. At the same time, the Nationalist Party’s endemic corruption not only cost it popular support but also allowed Communists to infiltrate its ranks by buying positions in government offices and even the secret police.

4 of 4

On the international stage, the Communist victory on the Chinese mainland shaped the politics of East Asia, and of US-China relations, for decades. In the US, the loss of China as an ally began to poison the political atmosphere of the early Cold War.

The United States supported the Nationalists by requiring Japanese forces to surrender only to official Nationalist armies, except in Manchuria, where they were to surrender to the Soviet Union. Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek ordered Japanese troops to continue fighting the Communists a full month after Japan’s official surrender, while Nationalist troops were readied to return to eastern China. Although officially neutral, the United States helped transport half a million Nationalist troops out of the southwest; the majority of Japanese arms and equipment went to Nationalist armies.

1 of 2

The civil war created a dynamic that the government, for all its police powers in the cities, could scarcely control. Blame for the foreign presence – US troops being the most obvious – fell on the government. The foreign soldiers quickly lost their mantle as liberators; stories were spread of American soldiers driving over pedestrians, beating rickshaw pullers, and even shooting at people they suspected of robbing them. A rape case involving US soldiers in Beijing in 1946 provoked Chinese students to take to the streets.

2 of 2

As 1945 turned into 1946, US President Harry Truman made it clear that he would not allow American military forces to fight for the Nationalist government.

Japanese Invasion of China During the Second Sino-Japanese War

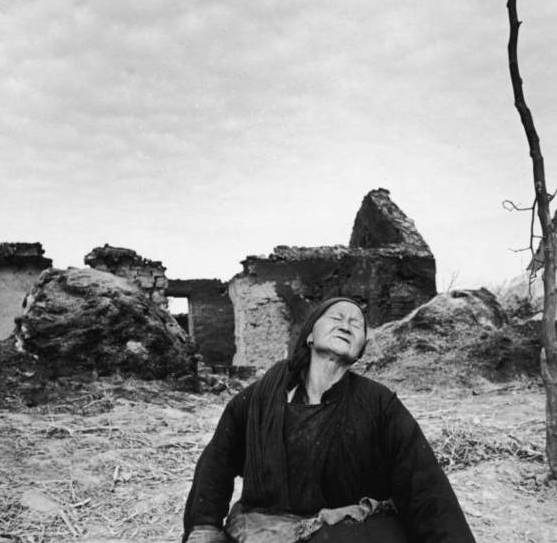

In 1937 what seemed at first a minor border skirmish near Peking quickly escalated into a full scale war between the Chinese and Japanese. The Japanese invasion of China had disastrous consequences for the Chinese: within the next year of fighting major cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Wuhan fell to the Japanese.

Resisting Alone: China’s Defensive War Against Japan

After 1938 the nature of the war in China changed: the gigantic clashes of the first 2 years were fewer in number. As the Chinese started focusing on defensive actions, and guerilla warfare in the occupied areas, the Japanese tried to subdue the locals by staging a number of offensives.

Second Sino-Japanese War: a war of alliance

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, China finally found some much needed allies as the US and British Empire entered the war against Japan. In 1944 Japan launched a massive offensive in China, code named Operation Ichi-go, during which Henan province fell to Japanese troops. However, despite this massive effort, China still did not surrender.

Japan's defeat in the Second Sino-Japanese War

Germany was defeated in May 1945. Preparations immediately began for a final assault on Japan that might involve massive numbers of Chinese troops. Instead, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August forced Japan’s sudden surrender, which took most of the world, including China’s leaders, by surprise.

- Peter Zarrow, China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949, Routledge, New York, 2005

- Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival, Allen Lane, London, 2013

- Odd Arne Westad, Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750, Basic Books, New York, 2012