Resisting Alone: China’s Defensive War Against Japan

China’s defensive war against Japan

1939 - 1941

After 1938 the nature of the Sino-Japanese war changed from offensive to defensive. The dramatic battles of the first year of the war were fewer in number. Instead, China's fate became tied up with shifting alliances, diplomatic intrigues and social change that would permanently alter the country's course. Central to those changes were new ideas of social provision: the circumstances of war forced the new regimes into competition with each other. Nationalists and Communists would strive to demonstrate that as the state demanded more of its people, so they should demand more of their government.

1 of 6

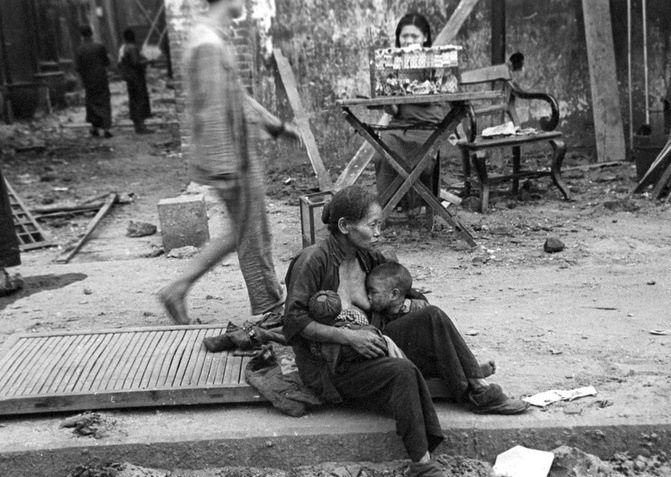

Although within China and in the outside world Chongqing was painted as a fierce center of resistance, the reality was rather less impressive. The city was ill-equipped for the massive refugee flight, and quickly became dotted with different types of temporary housing. Such hastily built dwellings were hardly a surprise in a desperately poor city suddenly thrust into national and international prominence. Chongqing's population had soared as refugees poured into Free China. Sichuan province served as a major base for the government's plans for resistance and reconstruction.

2 of 6

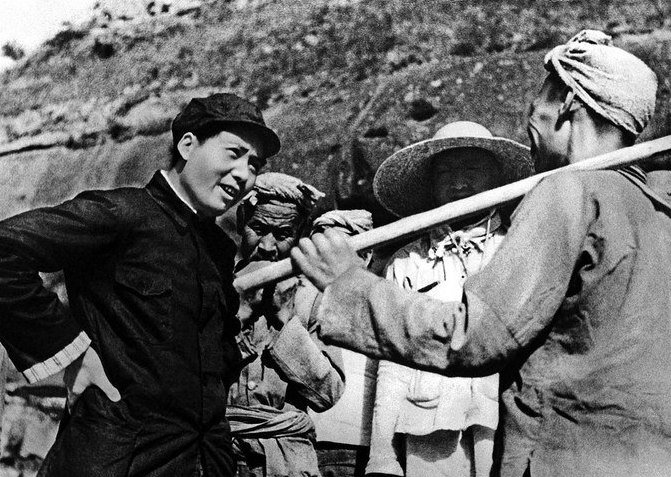

When they wrote their memoirs, the outsiders who visited the Communist capital at Yan'an in Shaanxi province came back, over and over again, to the subject of food. Food was rationed carefully and there was little variation, although mothers with children were given extra meat. Wartime Yan'an was stark and regimented, particularly for those who had accepted the discipline of the party. Even more than in Chongqing, Yan'an was the testing-ground for a new social contract. The party and state promised deeper commitments to social provision, but demanded complete obedience in return.

3 of 6

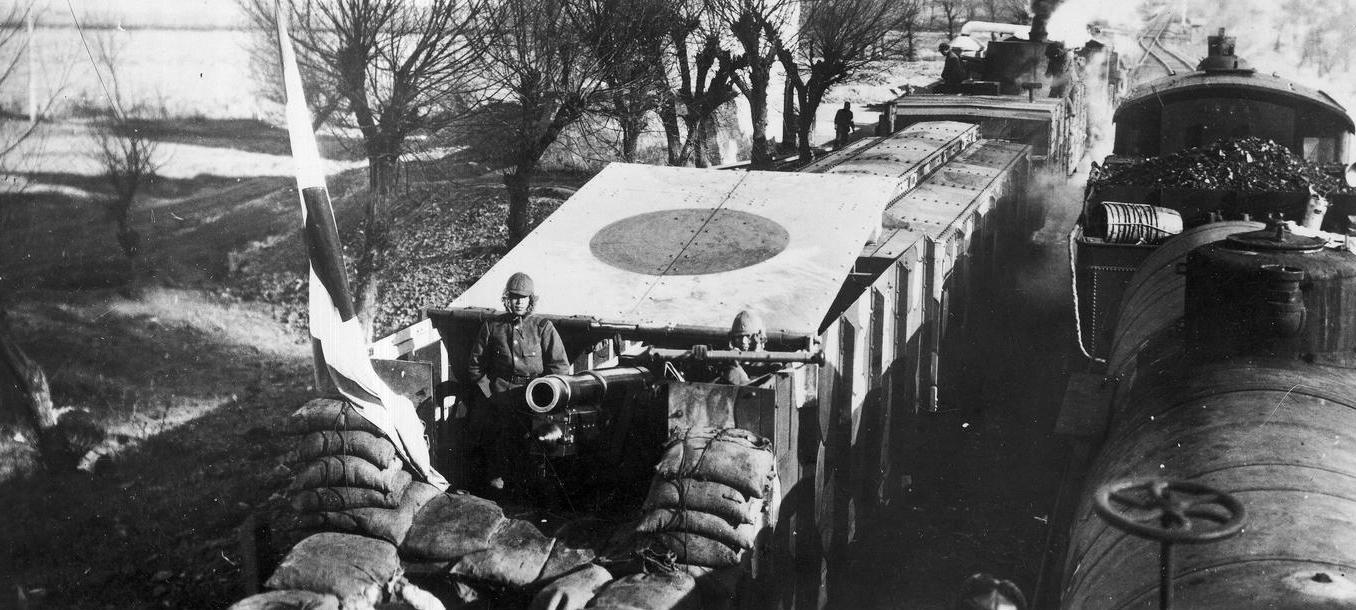

From September 1939 until the spring of 1941, the Nationalists could not count on any meaningful foreign support. Internationally, the situation was highly fluid, with no one clear about the final shape of the international alliances that would slug it out on the battlefield. During this period, with the Japanese no longer threatened by the Soviet Union, the fighting moved to south China. The Japanese redoubled their efforts to bottle the Nationalists up in Sichuan, including large-scale strategic bombing campaigns. The Nationalists continued their efforts to keep the war going across China, and were able to defeat a Japanese offensive aimed at taking Changsha.

4 of 6

The period between the fall of Wuhan and the beginning of Japan’s Southern Advance has often been characterized as a stalemate. It is certainly true that after the Battle of Wuhan the choreography of the war changed. Beforehand, hundreds of thousands of Chinese and Japanese troops engaged each other in the deathly dance of set-piece battles on a stage hundreds of miles long and wide. Afterwards, the war became diffuse and dispersed, with little activity in some areas for long periods of time.

5 of 6

The altered nature of the war was the result of changes in Japanese and Chinese strategy. Neither side desired to continue with the large-scale military operations that had characterized the first phase of the war. While the Japanese had come to the conclusion that they could not secure a quick military victory but must also rely on political means, for the Nationalists it was even more true that a military victory in the short term was impossible. However, prevailing in the war and imposing their visions remained the goal for both.

6 of 6

The Nationalist approach during the second phase of the War of Resistance can be described as establishing a series of fortress zones across China designed to interdict Japanese lines of communication, offer a multiplicity of targets so that the Japanese were forced to dilute their forces, and keep the war going across China as a national endeavor. The major base was Sichuan, which provided by far the most recruits for the army as well much of its food.

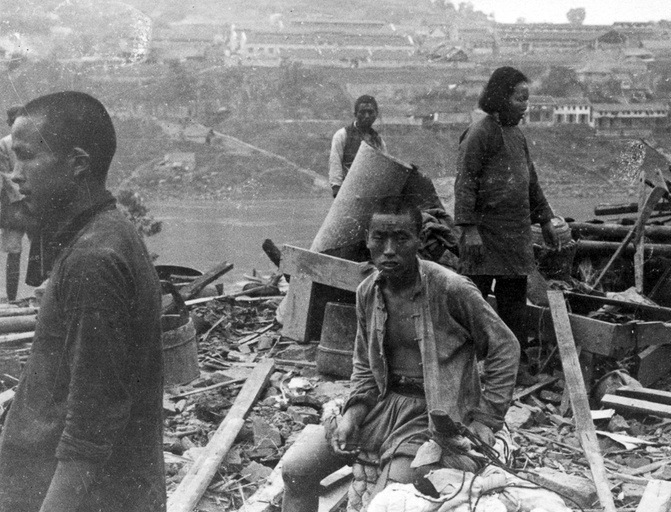

Many aspects of life in the city of Chongqing were beyond the Nationalist government's control, and none more so than the terrifying new reality of constant bombings. In the winter of 1938 there were a few 'trial raids' on the city. The attacks began in earnest from the spring of 1939, and it was the destruction that rained down on the twentieth anniversary of the nationalist Fourth of May demonstrations which marked the start of a stream of destruction from the sky that would be part of everyday existence for years to come.

1 of 4

The raids happened in spring and the height of the summer, when the city was at its hottest, with temperatures reaching more than 40 degrees Celsius. In the shelters, as the Chongqingers awaited the raids, the atmosphere was stifling, and people brought hand fans to keep themselves cool.

2 of 4

The authorities recruited professional body-carriers to deal with the corpses of people killed in the raids, and they would be paid the equivalent of one jin (half kilogram) of rice per body carried. The corpses would be buried together at a spot named the 'new coffin mountain', having been transported on one of the boats which shipped bodies out of the city. At the height of the raids, more than a hundred boats operated at a time.

3 of 4

As the May 1939 raids showed, even if the all-clear had sounded, another raid might be imminent, and people became used to the idea of settling down in the hot, dark shelters for days at a time. Their emergency kits and toilet arrangements would last for a couple of days, but after that, they were at the mercy of enterprising vendors who were willing to brave the raids to sell overpriced essentials to the families trapped in stifling, lightless conditions. Emerging after five or six days in the shelter was a painful process for some, as their eyes simply were not used to the bright sunshine.

4 of 4

Chongqing's air-raid defenses remained weak, largely because the alternative would have required a swift increase in China's aerial warfare capacity, as well as anti-aircraft weapons and other equipment that the country simply did not possess. Chiang's wife Song Meiling addressed the problem in 1937 by recruiting one of the more remarkable figures to work in wartime China: retired US Air Force Major-General Claire Lee Chennault. Chennault took over the training of China's still minimal air force. He also recruited pilots from the US who might be better able to take on Japanese fighters. The group was officially known as the American Volunteer Group (AVG), but it soon became much better known by its nickname, the Flying Tigers.

Japanese Invasion of China During the Second Sino-Japanese War

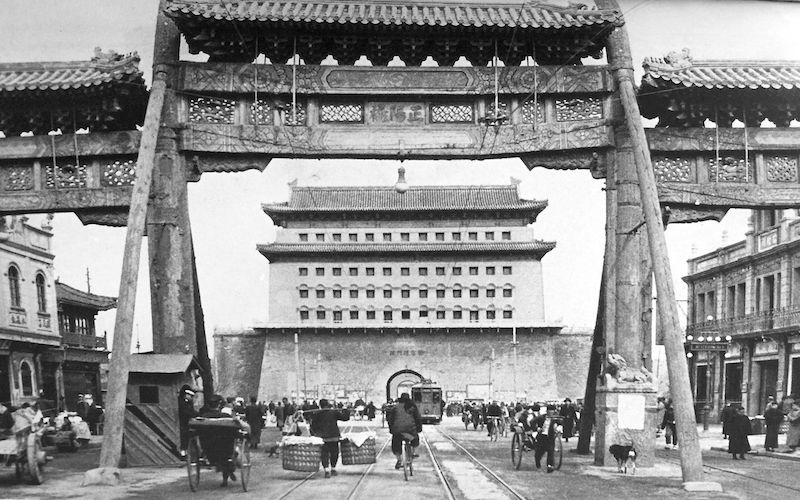

In 1937 what seemed at first a minor border skirmish near Peking quickly escalated into a full scale war between the Chinese and Japanese. The Japanese invasion of China had disastrous consequences for the Chinese: within the next year of fighting major cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Wuhan fell to the Japanese.

Second Sino-Japanese War: a war of alliance

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, China finally found some much needed allies as the US and British Empire entered the war against Japan. In 1944 Japan launched a massive offensive in China, code named Operation Ichi-go, during which Henan province fell to Japanese troops. However, despite this massive effort, China still did not surrender.

Japan's defeat in the Second Sino-Japanese War

Germany was defeated in May 1945. Preparations immediately began for a final assault on Japan that might involve massive numbers of Chinese troops. Instead, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August forced Japan’s sudden surrender, which took most of the world, including China’s leaders, by surprise.

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a war between the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Communists that started in the late 1920's. After the end of the Second World War and Japan's defeat the civil war resumed and the Communists were eventually victorious.

- Peter Zarrow, China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949, Routledge, New York, 2005

- Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival, Allen Lane, London, 2013

- Hans van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China, 1925-1945, Routledge-Curzon, London, 2003