Second Sino-Japanese War: a war of alliance

Allied involvement in the Second Sino-Japanese War

1942 - 1944

After the US and the British Empire entered the war against Japan, China suddenly found itself in a coalition she had long hoped for. However, in the years that followed, coalition warfare proved a difficult challenge for China as tensions between her and the US increased. Chinese troops were sent into combat in Burma, a move that the Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek was forced to make under pressure from his allies. In 1944 a new major Japanese offensive in central China was launched, but again, the Chinese managed to avoid capitulating.

1 of 7

The years following Pearl Harbor saw a distinct and growing division in the choices of the major political actors. In the early years of the war, both the Nationalists and Communists had stressed the pluralist and cooperative parts of their program. This was a sensible move for parties that had to gain as much leverage as possible both with their own people and with the outside world. But both the Nationalist and Communists ultimately envisaged a modernized China in which only one party would have a dominant role, a goal not compatible with true pluralism.

2 of 7

Japan’s main goal was to conquer Southeast Asia: Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines and Burma, as well as the Western Pacific islands. The Japanese conquest of Burma was completed by June 1942, thus severing Chongqing’s main link with its allies and threatening it from the south. Given Britain’s weakness, the defense of Burma had been largely in the hands of Chinese troops under the command of the American General Joseph Stilwell. Chiang, who had basically opposed the campaign from the beginning, was bitterly disappointed and blamed both the British and Stilwell for the defeat. Stilwell, in turn, formed a very low opinion of Chinese army officers up to and including Chiang.

3 of 7

The year 1943 would be one of deepening mistrust between the Allies, as China, Britain and the US circled each other with ever greater wariness. By the end of the year, Chiang would find that the roller-coaster of US-China relations would fling him from triumph to disaster, in locations as far apart as the sands of Egypt and the jungles of Burma.

4 of 7

The Japanese poured men into China in order to prevent the allies from gaining access to airfields there – which would be close enough for them to bomb Japanese cities. But the American advance was inexorable, and Japan faced steady bombardment from 1944. Although the Allies were doing well by 1944-5, Chiang had permanently lost a significant number of quality troops – which would hurt the Nationalists in the coming civil war against the Communists.

5 of 7

By creating a fiction that Chiang had to fight to show his value to the alliance, the Allies allowed the relationship between the US and China to erode. Rather than trying repeatedly to take Burma, a target of dubious value, it would have been perfectly reasonable to let Chiang use his limited resources to defend China, even if, in publicity terms, it appeared that China was not playing an active role in the wider war effort.

6 of 7

Chiang's regime was made complicit in thankless and over-ambitious goals, giving the impression that China's own goals and priorities always had to give way to those of the Western Allies and the USSR. The seeds were sown for mistrust between the US and China that would continue after the eventual Communist victory in 1949. Even today, the state of US-China relations shows that those wounds are far from being healed.

7 of 7

The Nationalists could not prevent a radical decline in the combat effectiveness of most of their forces. Troops living off the land do not easily move to far-away fronts for offensive duties. Nationalist guerrilla forces became indistinguishable from bandit troops and became a liability. Many war zones became independent satrapies of limited allegiance to Chongqing. The Communists accumulated substantial armies.

Until Pearl Harbor, the war in China had been a distant concern for the Americans and the British, distracted at home by the Depression and then the war in Europe. For the many westerners who remained in China after 1937, the war was an everyday reality, but their protected status as foreign neutrals always gave them some measure of distance as well as protection, particularly for those who remained in the zones controlled by the Japanese. Now, though, they were enemy aliens. All across eastern China, Americans and Britons were rounded up and interned. For some, this harsh environment would be home until the end of the war, if they survived at all.

1 of 2

The International Settlement of Shanghai, for so long an oasis of neutrality in the midst of a war-torn city, was now reunified under Japanese control. In that city thousands of foreigners with Allied nationality were sent to holding camps.

2 of 2

An eleven-year-old British boy, Jim Ballard, became a teenager in Longhua, a holding camp of some 2,000 people. Forty years later, as the novelist J. G. Ballard, he told a semi-autobiographical version of his story in Empire of the Sun, detailing the hunger, cold and disease which were the everyday fate of Longhua's residents.

Japanese Invasion of China During the Second Sino-Japanese War

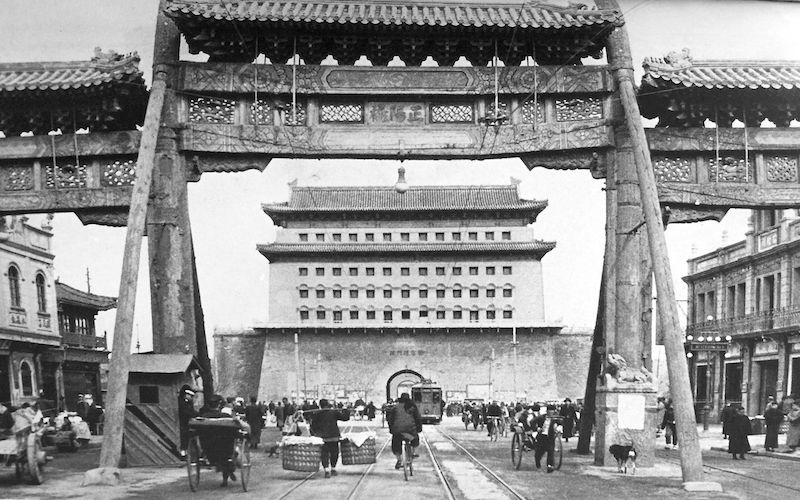

In 1937 what seemed at first a minor border skirmish near Peking quickly escalated into a full scale war between the Chinese and Japanese. The Japanese invasion of China had disastrous consequences for the Chinese: within the next year of fighting major cities such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Wuhan fell to the Japanese.

Resisting Alone: China’s Defensive War Against Japan

After 1938 the nature of the war in China changed: the gigantic clashes of the first 2 years were fewer in number. As the Chinese started focusing on defensive actions, and guerilla warfare in the occupied areas, the Japanese tried to subdue the locals by staging a number of offensives.

Japan's defeat in the Second Sino-Japanese War

Germany was defeated in May 1945. Preparations immediately began for a final assault on Japan that might involve massive numbers of Chinese troops. Instead, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August forced Japan’s sudden surrender, which took most of the world, including China’s leaders, by surprise.

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a war between the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Communists that started in the late 1920's. After the end of the Second World War and Japan's defeat the civil war resumed and the Communists were eventually victorious.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011

- Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2007

- Peter Zarrow, China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949, Routledge, New York, 2005

- Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival, Allen Lane, London, 2013

- Hans van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China, 1925-1945,Routledge-Curzon, London, 2003