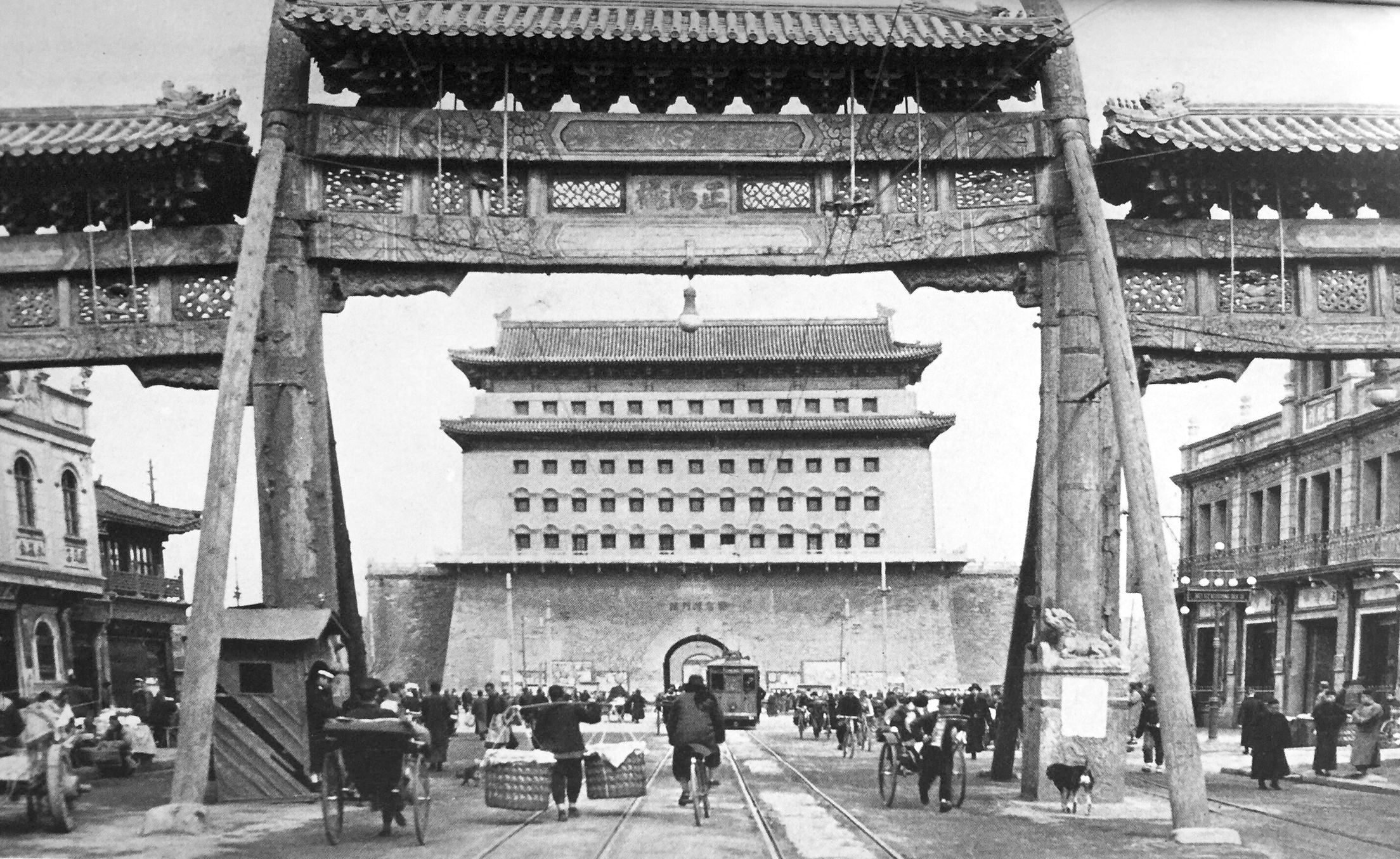

Japanese Invasion of China During the Second Sino-Japanese War

The origins and start of the Second-Sino Japanese war

1937 - 1938

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a conflict fought between China and the Empire of Japan. It began in 1937 and by 1941 was merged with other conflicts of the Second World War as a major theater known as the China-Burma-India theater. The war came as a result of Imperial Japan's ambitions to expand its borders in order to secure much- needed resources required for national expansion. Initially the Japanese achieved major victories, capturing both Shanghai and the Chinese capital of Nanking. By 1939 however, the war had reached a stalemate, with the Japanese unable to defeat the Chinese.

1 of 4

As early as 1936, American correspondent Edgar Snow, a passionate admirer and friend of Mao Zhedong, wrote: ‘In her great effort to master the markets and inland wealth of China, Japan is destined to break her imperial neck. This catastrophe will occur not because of automatic economic collapse in Japan. It will come because the conditions of suzerainty which Japan must impose on China will prove humanly intolerable and will shortly provoke an effort of resistance that will astound the world.’ Snow was right about the outcome of Japanese imperialism, though not about the military effectiveness of Chinese resistance.

2 of 4

Between 1937 and 1942, both nationalists and communists inflicted substantial casualties on the invaders – 181,647 dead. But thereafter they acknowledged their inability to challenge them in headlong confrontations which drained their threadbare resources to little purpose. Chinese historian Zhijia Shen has written in a study of Shandong province: ‘Local people were much more influenced by pragmatic calculation than by the idea of nationalism … When national and local interests clashed, they did not hesitate to compromise national interests.’

3 of 4

The occupation of half of China constituted a massive drain upon Tokyo’s resources. The country was vast: even if organized opposition was weak, large forces were indispensable to make good Tokyo’s claims on territory, and to control a hostile and often starving population.

4 of 4

The Battles of Shanghai, Xuzhou, and Wuhan are usually described separately, as if they were events that followed each other without connection. They were in fact closely linked in strategy on the Nationalist side, although not for the Japanese, and can only be understood in relation to each other. If the Battle of Shanghai initiated full-out war, the Battle of Xuzhou was the critical encounter. Following the fall of Shanghai and Nanjing, Xuzhou provided the best opportunity for a counter-offensive.

The Japanese were the only large-scale wartime users of biological weapons. Unit 731 in Manchuria operated under the cover name of the Kwantung Army Epidemic Protection and Water Supply Unit. Thousands of captive Chinese were murdered in the course of tests at 731’s base near Harbin, many being subjected to vivisection without the benefit of anaesthetics. Some victims were tied to stakes before anthrax bombs were detonated around them. Women were laboratory-infected with syphilis; local civilians were abducted and injected with fatal viruses. In the course of Japan’s war in China, cholera, dysentery, plague and typhus germs were broadcast, most often from the air, sometimes with porcelain bombs used to deliver plague fleas.

1 of 2

That the Japanese attempted to kill millions of people with biological weapons is undisputed; it is less certain, however, how successful their efforts were. Vast numbers of Chinese died in epidemics between 1936 and 1945, and modern China attributes most of these losses to Japanese action. In a broad sense this is just, since privation and starvation were consequences of Japanese aggression. But it remains unproven that Unit 731’s operations were directly responsible.

2 of 2

Over 200,000 people died during the 1942 cholera epidemic in Yunnan. The Japanese released cholera bacteria in the province, but many such epidemics took place even where they did not do so. It was difficult, with available technology, to spread disease on demand with air-dropped biological weapons. Yet even if Japan’s genocidal accomplishments fell short of their sponsors’ hopes, the nation’s moral responsibility is manifest.

Resisting Alone: China’s Defensive War Against Japan

After 1938 the nature of the war in China changed: the gigantic clashes of the first 2 years were fewer in number. As the Chinese started focusing on defensive actions, and guerilla warfare in the occupied areas, the Japanese tried to subdue the locals by staging a number of offensives.

Second Sino-Japanese War: a war of alliance

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, China finally found some much needed allies as the US and British Empire entered the war against Japan. In 1944 Japan launched a massive offensive in China, code named Operation Ichi-go, during which Henan province fell to Japanese troops. However, despite this massive effort, China still did not surrender.

Japan's defeat in the Second Sino-Japanese War

Germany was defeated in May 1945. Preparations immediately began for a final assault on Japan that might involve massive numbers of Chinese troops. Instead, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August forced Japan’s sudden surrender, which took most of the world, including China’s leaders, by surprise.

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a war between the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Communists that started in the late 1920's. After the end of the Second World War and Japan's defeat the civil war resumed and the Communists were eventually victorious.

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011

- Peter Zarrow, China in War and Revolution, 1895-1949, Routledge, New York, 2005

- Rana Mitter, China’s War with Japan, 1937–1945: The Struggle for Survival, Allen Lane, London, 2013

- Hans van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China, 1925-1945,Routledge-Curzon, London, 2003