War at Sea during Word War II

U-boat terror in the Atlantic and the Arctic convoys

The British Army’s part in the struggle against Nazism was vastly smaller than that of the Russians, as would also be the US Army’s contribution. Britain’s principal strategic importance became that of a giant aircraft carrier and naval base, from which the bomber offensive and the return to the Continent were launched. It fell to the Royal Navy to conduct the critical struggles of 1940-43 to keep the British people fed, to hold open the sea lanes to the Empire and overseas battlefields, and convoy munitions to Russia.

1 of 5

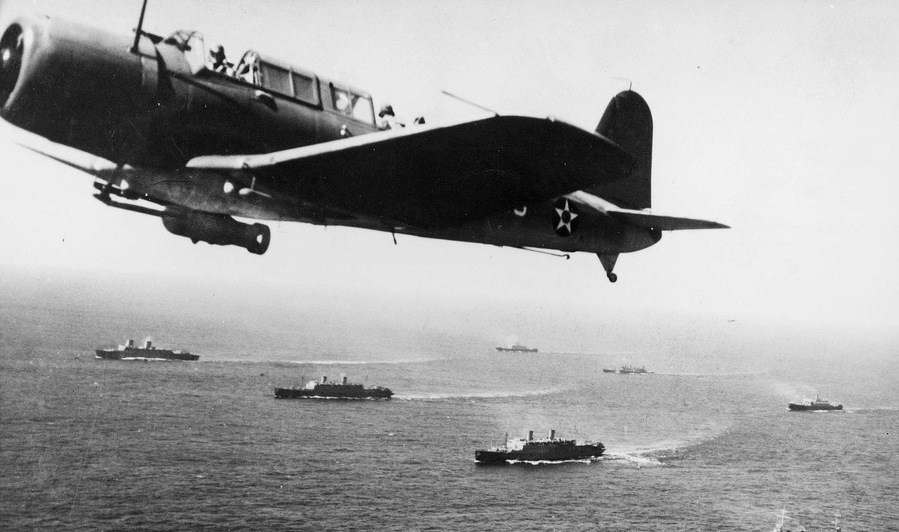

Naval might could not bring about the defeat of Germany, nor even protect Britain’s eastern empire from the Japanese. It was a fundamental problem for the two Western Allies that they were sea powers seeking to defeat a great land power, which required a predominantly Russian solution. But if German efforts to interdict shipments to Britain were successful, Churchill’s people would starve. A minimum of twenty-three million tons of supplies a year – half the pre-war import total – had to be transported across the Atlantic in the face of surface raiders and U-boats.

2 of 5

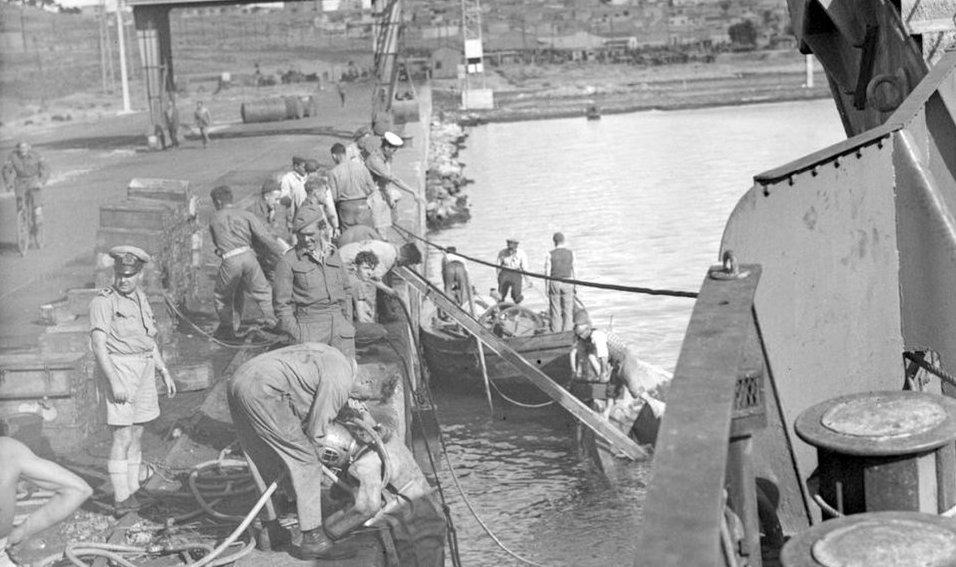

The navy had suffered as severely as Britain’s other services from inter-war retrenchment. The construction of big ships required years, and even a small convoy escort took months to build. Britain built and repaired ships more slowly, if much more cheaply, than the United States, and could never match American capacity. For the Royal Navy, shortage of escorts was a pervasive reality of the early war years.

3 of 5

In the first war years, Germany’s surface raiders imposed as many difficulties as U-boats: the need to divert convoys from their danger zones increased the strain on British merchant shipping resources. German sorties between 1939 and 1943 precipitated dramas which seized the attention of the world: the pocket battleship Graf Spee sank nine merchantmen before being scuttled after its encounter with three British cruisers off the River Plate in December 1939. The 56,000-ton Bismarck destroyed the battlecruiser Hood before being somewhat clumsily dispatched by converging British squadrons in May 1941. The British public was outraged when the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau made a dash to Wilhelmshaven from Brest through the Channel Narrows in February 1942, suffering only mine damage amid fumbling efforts by the navy and RAF to intercept them. The presence of Tirpitz in the fjords of northern Norway menaced British Arctic convoys and strongly influenced Home Fleet deployments until 1944.

4 of 5

Hitler never understood the sea. In the early war period, he dispersed industrial effort and steel allocations among a range of weapons systems. He did not recognize a strategic opportunity to wage a major campaign against British Atlantic commerce until the fall of France in June 1940. U-boat construction was prioritized only in 1942-43, when Allied naval strength was growing fast and the tide of the war had already turned. Germany never gained the capability to sever Britain’s Atlantic lifeline, though amid grievous shipping losses it was hard to recognize this at the time.

5 of 5

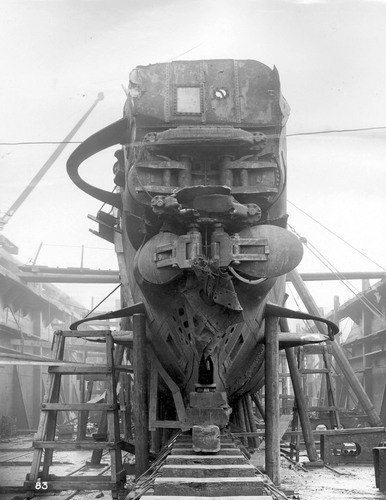

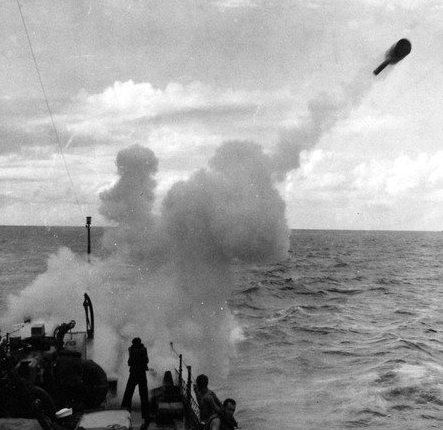

Major scientific and technical developments during the war helped in the struggle against the U-boat. The Royal Navy used Asdic, the echo-sounding device for tracking U-boats, and 180 ships were fitted with it. It was not foolproof, however, so ships constantly zig-zagged hoping to escape submarines.

The Germans might have improved their chances of winning the war if they had never prosecuted the Battle of the Atlantic but had expended all their resources on the air and ground campaigns. The Third Reich lacked the resources to fight a world war on so many fronts, and war demands hard choices. But Hitler’s method of decision-making, coupled with the inability of the German military to think at the strategic level, made it impossible for leaders of the Third Reich to make the choices that might have brought them victory.

1 of 6

It was not so much the successes and failures of the U-boats themselves as the indirect effects of the U-boat offensive that helped turn the war against Germany. Without the terrible losses inflicted by the U-boats in the summer and fall of 1940, the United States might never have embarked on its massive program to construct merchant shipping. The German successes off the east coast of the United States in early 1942 added even greater impetus to Roosevelt’s support for the program.

2 of 6

As was so often the case with their strategic assessments, the Germans had underestimated their opponents. The efforts of Bletchley Park played a crucial role in deflecting the U-boat offensive, particularly in the last half of 1941, when the British were most vulnerable. In spite of great circumstantial evidence that the British had broken into their codes, the Germans refused to believe the evidence because of their confidence in the superiority of their technology. As a result of this arrogance, the British were able to tip the playing field against the U-boats for virtually the entire last half of the war.

3 of 6

Cryptanalysis alone cannot account for the failure of the German naval effort. At the start of the war Dönitz tapped a relatively small staff to control the U-boat battle against British commerce. As the campaign against British commerce expanded and became ever more complex, the German staff at U-boat Headquarters remained at the same small staffing levels; if anything, it contracted, as Dönitz attempted to close off what the Germans regarded as human leaks in their security systems. A number of important consequences flowed from this decision. Most obvious was the general exhaustion of all the officers involved in running the U-boat campaign. But more disabling was the inability of U-boat Headquarters to step back and take a longer look at the war, both to assess its intelligence situation and to implement technological improvements.

4 of 6

As was so typical of the German approach to war, Dönitz fully seconded Raeder’s efforts to get Hitler to declare war on the United States in the second half of 1941. Yet, when that declaration of war came, instead of concentrating his submarines for a deadly strike against the east coast of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean, Dönitz committed his boats in small numbers. The damage they wrought was considerable, but in the end it merely forced the United States to devote sufficient naval forces and resources to the problem without delivering irreparable damage to the Allied cause.

5 of 6

The Allies eventually won the Battle of the Atlantic, but at a needlessly high cost. The armed forces’ lack of interest in anti-submarine warfare before the outbreak of the war was inexcusable, especially in light of their experiences in World War I. When the threat emerged again early in World War II, anti-submarine forces received the attention they deserved, but by then it took the most desperate measures, including putting the entire British nation on a near starvation diet, to overcome the challenge.

6 of 6

The effort to thwart the U-boats was one of the high points of war for the British. When its leaders recognized the threat, the Royal Navy developed the tactics, the technology, and the leadership to handle the grim business of anti-submarine warfare. The integration of technology into effective tactical systems was crucial to mastering the U-boats in 1943; similarly, the integration of intelligence into the conduct of anti-submarine and convoy operations substantially boosted the chance of victory. The mental flexibility of those responsible for the anti-submarine campaign allowed the British to get maximum utility out of civilian scientists, reserve intelligence officers, and operations research analysts.

World War Two In Perspective

The Second World War was the most destructive conflict in human history. It shaped the world into what it is today. If nothing else, we ought at least to remember the most destructive war in history and the terrible tragedies it wrought.

Why Germany lost World War Two and why the Allies won?

The Axis lost the war because of a series of tactical mistakes that, at the time, might have seemed the best choices of limited options. At the same time, the Allies won the war through a genuine team effort, and at great cost both financially and in the terms of human lives

How was World War Two fought?

World War Two was fought with a wide variety of weapons from all countries that fought in the conflict. As the war progressed, new and more deadly weapons were deployed on the world's battlefields.

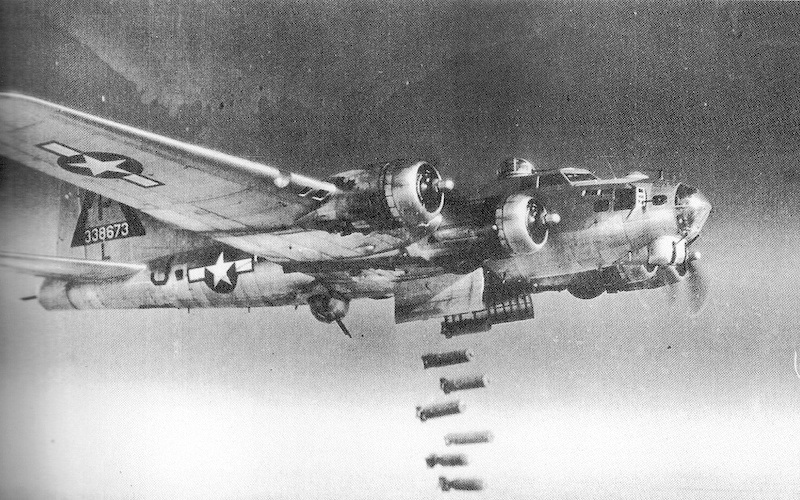

Allied bombing of Germany

As distasteful as these bombing campaigns are today to most citizens of the liberal democracies under sixty years of age, the Combined Bomber Offensive in Europe and the bombing of Japan reflected not only a sense of moral conviction on the part of the West but a belief that such air attacks would end a war that daily grew more horrible for soldiers and civilians alike.

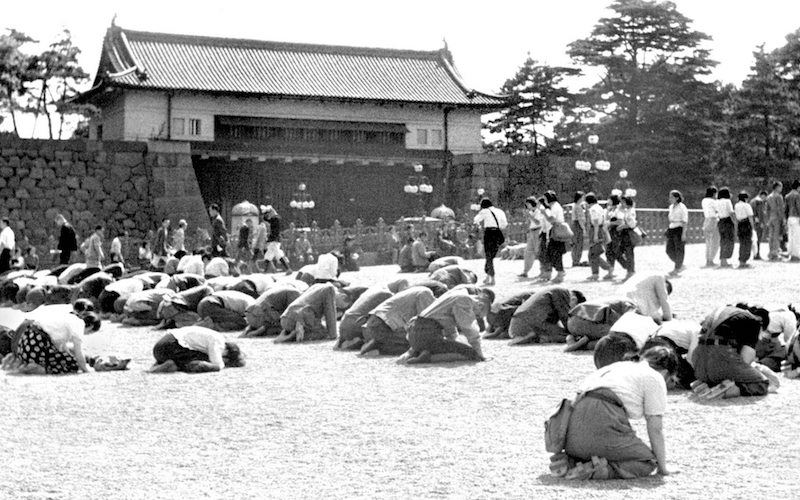

Asia after World War Two

World War Two fundamentally changed the destinies of China, Japan, Korea and South East Asia. Each country faced new challenges after the war, often as a direct consequence of the war, challenges that would shape their destinies for decades to come.

Home Front during World War Two

The industry had to accelerate the production of war matériel. The warring countries had to galvanize their societies for war in order to maintain morale, and to mobilize their soldiers. Countries under occupation tried to organize resistance movements with varying degrees of success.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011