Home Front during World War Two

War mobilization around the globe

Nikolai Belov of the Red Army wrote in his diary at the end of 1942: ‘Yesterday I received a whole bunch of letters from Lidochka. I sense that she isn’t having an easy time back there with the little ones.’ Captain Belov understated his wife’s predicament. During the war, civilians suffered more than soldiers in many societies. Although statistics are drastically distorted by the mortality in Russia and China, it is notable that globally more non-combatants perished between 1939 and 1945 than uniformed participants.

1 of 7

Romanian Mihail Sebastian never saw a battlefield, but wrote in December 1943: ‘Any personal balance sheet gets lost in the shadow of war. Its terrible presence is the first reality. Then somewhere, far away, forgotten by us, are we ourselves, with our faded, diminished, lethargic life, as we wait to emerge from sleep and start living again.’

2 of 7

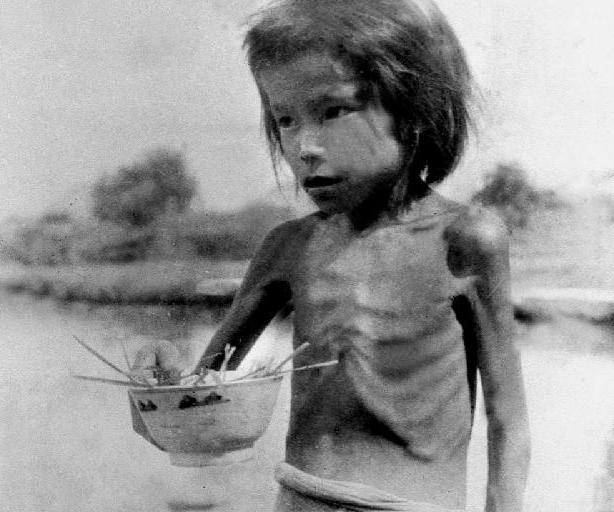

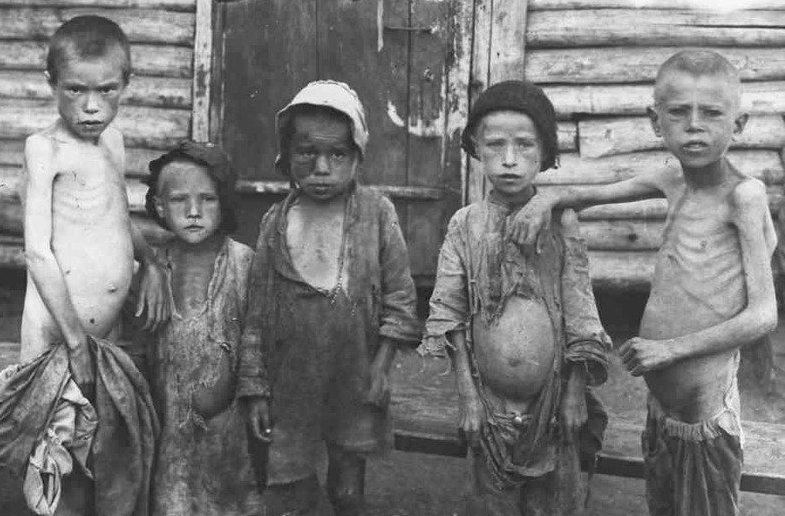

It is hard to use the phrase ‘home front’ without irony in the context of Russia’s war, in which tens of millions found themselves in the condition described by Ukraine partisan Commissar Pavel Kalitov in September 1942, at the hamlet of Klimovo: ‘A pale, thin woman sits on a bench with a baby in her arms and a girl of about seven. She is weeping, poor wretch. What are her tears about? I would do anything to be able to help these miserable human beings, to ease their pain.’ Three weeks later, he described a similar scene in Budnitsa: ‘What is left of it? Heaps of ruins, chimneys sticking out, scorched chairs. Where there were roads and paths, there are thorns and weeds. No sign of life. The village is under constant artillery fire.’ Shortly afterwards, Kalitov’s unit received an army order to clear all civilians from a fifteen-mile zone behind the front; they were to be permitted to take their belongings, but no forage or potatoes. Kalitov wrote unhappily: ‘We’ve got to work with the civilians, to prepare them so that they do this without resisting. It’s a tough business: many people are living almost entirely off potatoes. To demand that they leave these for the troops means sentencing them to terrible hardships, even death. A family of refugees stands in front of me now. They are so thin and gaunt, one can see through them. It is especially hard to look at the little ones – three of them, one a baby, the others a little older. There is no milk. These people have suffered as much as us, the soldiers, or even more. Bombs, shells and mines no longer scare them.’

3 of 7

In the unoccupied Western nations, some people prospered: criminals exploited demand for prostitution, black market goods, stolen military fuel and supplies; industrialists made enormous profits, many of which somehow evaded windfall taxes; farmers experienced greater prosperity than they had ever known, especially in the United States, where incomes rose by 156 percent. ‘Farm times became good times,’ said Laura Briggs, daughter of an Idaho smallholder. ‘Dad started having his land improved … We and most other farmers went from a tarpaper shack to a new frame house with indoor plumbing. Now we had an electric stove instead of a wood burning one, and running water at the sink where we could do the dishes; and a hot water heater; and nice linoleum.’ But far more people hated it all.

4 of 7

In April 1941, Edward McCormick wrote to his son David, who had enlisted with his brother Anthony, and now embarked with an artillery regiment for the Middle East. ‘To Mummy, in particular,’ their father said, ‘the whole war centers round you and Anthony. The chief motivating force in her life, ever since you were born, has been your health, happiness and safety. These are still her instinctive thoughts, and you don’t need me to tell you therefore how devastating this parting with you both has been to her. I feel it too, and it appalls me to think of the hardship, danger and filth which will probably be your experience. There is no doubt whatever, in my mind, that this war had to come. A Nazi victory can only mean the enjoyment of life by a very small number of chosen Germans, and the souls of all people under them will be engulfed. You and Anthony are helping to rid the world of this plague and, while personal feelings make me wish you were far away from it all, I am filled with pride … at what I know you will achieve. Mum and I send you our fondest love and blessings and pray for your wellbeing and safe return to us. DAD’ It would be more than four years before the McCormick family was reunited, a separation common to scores of millions. And although enlistment in uniform was the commonest cause of displacement and the sundering of families, these things also took many other forms.

5 of 7

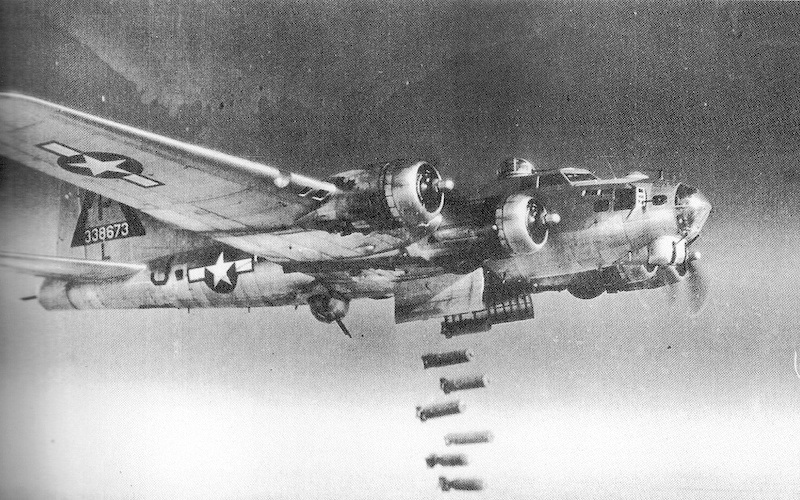

Bianca Zagari was a mother of two in a prosperous Italian family, who fled from their home city of Naples in December 1942, when American bombing began. A party of fourteen including in-laws, nephews and nieces, maid and governess, they settled in the remote and impoverished Abruzzo region, renting two houses in a village in the Sangro valley, accessible only on foot. There, they eked out an uncomfortable existence until, to their horror, in October 1943 once again bombs began to fall around them; they were only eighteen miles from Monte Cassino, in an area bitterly contested between the German and Allied armies. Zagari and her children fled with the villagers; as they clambered into the hills, a peasant told her, in local dialect she could barely comprehend, that the bombing had claimed most of her relations: ‘Signora, the ten dead are yours.’ She wrote: ‘Now it is dawn and others are climbing up from Scontrone, terrified. Each one gives me a horrific detail: a hand, a little foot, two plaits with red bows, a body without a head.’ Her husband Raffaele survived, but most of his family perished. The survivors existed for weeks in caves in the mountains, learning skills such as Zagari had never known – lighting fires and building rough shelters with scant help from the unsympathetic local people, who cared only for their own. ‘I have to ask for everything from everyone – it is like begging for alms.’ When the Germans found them, all the men were conscripted for forced labor: ‘They took one while he was digging under ruins for his mother.’ After months of misery, one day she fled across the mountains with her two children and her jewel case. Eventually a pitying German lorry-driver gave them a lift to Rome. ‘We arrive via the Porta San Giovanni. I feel I am dreaming – I see nannies with children playing calmly. The war seems a distant rumor. Everyone asks where we have come from. No one understands the answer that we have come from Scontrone where nine members of the family have been killed. At the Corso hotel, where the concierge knows us and tries to help, we hear another guest threatening that he will refuse to patronise the establishment again if it admits such vagabonds as ourselves.’ The Zagaris were able to exploit their wealth to deliver them from the worst privations, as most Italians could not.

6 of 7

People displaced from their homes and countries spent much of the war waiting: for orders or visas; for an opportunity to flee from looming peril; for permission to travel. Twenty-one-year-old English girl Rosemary Say, having escaped from German internment into the Vichy zone of France, kicked her heels for weeks in Marseilles among an unhappy community of fellow fugitives: ‘It was sad to see the waste of intellect and ability as the delays lengthened and the future for many continued to look bleak. Had he got his visa at last, had he been arrested or just scarpered into the countryside to try his luck? We waited and wondered. But if the person didn’t come back he was soon forgotten. We were only really held together by a common wish to be off and away and to begin our lives again … There was a lot of suspicion and hopelessness … Feelings ran high and quarrels were loud and violent. We all shared the worry of our uncertainty.’

7 of 7

Ukrainian teenager Stefan Kurylak was shipped westwards by the German occupiers to labor for an Austrian Alpine farming family, devout Catholics named Klaunzer. On first sighting the boy, Frau Klaunzer burst into tears; without knowing why, the young Ukrainian followed suit. It was explained to him that the Klaunzers’ son had been killed on the Eastern Front a few weeks before. Frau Klaunzer kept mouthing one of the few German phrases Stefan could understand: ‘Hitler no good! Hitler no good!’ Stefan was thereafter treated with kindness and humanity: he worked on the family land, not unhappily, until the end of the war, when his hosts begged him in vain to stay on as one of themselves. Few such experiences were so benign.

More than any other aspect of the war, food or lack of it emphasized the relativity of suffering. Globally, far more people suffered serious hunger, or indeed died of starvation, than in any previous conflict, including World War I, because an unprecedented range of countries became battlefields, with consequent loss of agricultural production. Even the citizens of those countries which escaped famine found their diets severely restricted.

1 of 7

Britain’s rationing system ensured that no one starved and the poor were better nourished than in peacetime, but few found anything to enjoy about their fare. A land girl, Joan Ibbertson, wrote: ‘Food was our obsession … In my first digs the landlady never cooked a second vegetable, except on a Sunday; we had cold meat on Monday, and sausage for the rest of the week. Sometimes she cooked potatoes with the sausage, but often she left us a slice of bread each. The two sausages on a large, cold, green glass plate greeted us on our return from a day on leeks or sprouts, and a three-mile cycle ride each way … A neighbour once brought round a sack of carrots, which he said were for the rabbits, but we benefited from this act of kindness … We had dried eggs once a week for breakfast, but the good lady in charge liked to cook it overnight, so it resembled, and tasted like, sawdust on toast. We had fishpaste on toast, too, some mornings … One Christmas we were allowed to buy a chicken. My bird was so old and tough that we could hardly chew through it.’

2 of 7

Any Russian or Asian peasant, or Axis captive, would have deemed carrot marmalade, a British war-time improvisation, a luxury. Kenneth Stevens was a prisoner in Singapore’s Changi jail. He wrote: ‘In this place one’s mind returns continually and dwells longingly on Food … I think of Duck and Cherry Casserole, Scrambled Eggs, Fish Scallops, Chicken Stanley, Kedgeree, Trifle, Summer Pudding, Fruit Fool, Bread & Butter Pudding – all those lovely things were made just perfectly “right” in my own home.’ Stevens died in August 1943 without ever again tasting such delicacies. Only in 1945 did his wife receive his diary from the hands of a fellow prisoner, and shared his anguished fantasizing from the brink of the grave.

3 of 7

The average height of French children shrank: girls by eleven centimeters and boys by seven centimeters between 1935 and 1944. Tuberculosis stimulated by malnutrition increased dramatically in occupied Europe, and by 1943 four-fifths of Belgian children were displaying symptoms of rickets. In most countries city-dwellers suffered more from hunger than country people, because they had fewer opportunities for supplementing their diet by growing their own produce. The poor lacked cash to use the black market which, in all countries, continued to feed those with means to pay.

4 of 7

In the matter of diet, Canada, Australia and New Zealand escaped lightly, and Americans scarcely suffered at all. Rationing was introduced to Roosevelt’s people only in 1943, and then on a generous scale. Gourmet magazine gushed tastelessly: ‘Imports of European delicacies may dwindle, but America has battalions of good food to rush to appetite’s defense.’ Meat was almost the only commodity in short supply, although Americans complained bitterly enough about that. A housewife named Catherine Renee Young wrote to her husband in May 1943: ‘I’m sick of the same thing … We hardly ever see good steak any more. And steak is the main meat that gives us strength. My Dad just came back from the store and all he could get was blood pudding and how I hate that.’ But whatever the shortcomings of wartime quality, in quantity American domestic meat consumption fell very little, even when huge shipments were exported to Britain and Russia.

5 of 7

Every nation with power to do so put its own people first, heedless of the consequences for others at their mercy. The Axis behaved most brutally, and with the direst consequences: Nazi policy in the east was explicitly directed towards starving subject races in order to feed Germans. The Japanese throughout their empire adopted draconian policies to provide food for their own people, which caused millions to starve in South-East Asia and China. Although the Allies were not responsible for anything like the human toll exacted by the Axis, their policies displayed a ruthless pragmatism. The United States insisted that both its people at home and its armed forces abroad should receive fantastically generous allocations of food, even when shipping space was at a premium. The British government, in its turn, imposed extreme privation on some of the peoples of its empire, to maintain the much higher standard of nourishment it deemed appropriate at home.

6 of 7

For Italians, hunger was a persistent reality from the moment the country became a battlefield in 1943. ‘Hunger governed all,’ Australian correspondent Alan Moorehead wrote from Italy. ‘We were witnessing the moral collapse of a people. They had no pride any more, or dignity. The animal struggle for existence governed everything. Food. That was the only thing that mattered. Food for the children. Food for yourself. Food at the cost of any debasement or depravity.’ Prostitution alone enabled some mothers to feed their families, as British Sergeant Norman Lewis witnessed in 1944. At a municipal building in the outskirts of Naples, he encountered a crowd of soldiers surrounding a group of women who were dressed in their street clothes, ‘and had the ordinary well-washed, respectable shopping and gossiping faces of working-class housewives. By the side of each woman stood a small pile of tins, and it soon became clear that it was possible to make love to any one of them in this very public place by adding another tin to the pile. The women kept absolutely still, they said nothing and their faces were as empty of expression as graven images. They might have been selling fish, except that this place lacked the excitement of a fish market. There was no solicitation, no suggestion, no enticement, not even the discreetest and most accidental display of flesh … One soldier, a little tipsy, and egged on constantly by his friends, finally put down his tin of rations at a woman’s side, unbuttoned and lowered himself onto her. A perfunctory jogging of the haunches began and came quickly to an end. A moment later he was on his feet and buttoning up again. It had been something to get over as soon as possible. He might have been submitting to field punishment rather than the act of love.’ That only a relatively small number of Italians died of starvation between 1943 and 1945 was due first to the illicit diversion of vast quantities of American rations to the black market, and thereafter to the people – much to the private enrichment of some US service personnel; and second to the political influence of Italian-Americans, which belatedly persuaded Washington of the case for averting mass starvation.

7 of 7

The Soviets’ plight was partially of their own making. When the Germans first invaded, Stalin ordered a scorched-earth policy rather than attempt to move foodstuffs to the east. While this policy might have defeated Napoleon in 1812, it made little difference to the Wehrmacht of 1941. Instead of slowing down the Germans, it starved Russians. At a time when the Soviet Union lost one-third of its people through death and occupation, its food resources dropped by 60 percent. Only soldiers and war-workers received adequate calories and proteins; older people, teenagers, and bureaucrats received the lowest rations. Even vodka was in short supply — a national crisis.

World War Two In Perspective

The Second World War was the most destructive conflict in human history. It shaped the world into what it is today. If nothing else, we ought at least to remember the most destructive war in history and the terrible tragedies it wrought.

Why Germany lost World War Two and why the Allies won?

The Axis lost the war because of a series of tactical mistakes that, at the time, might have seemed the best choices of limited options. At the same time, the Allies won the war through a genuine team effort, and at great cost both financially and in the terms of human lives

How was World War Two fought?

World War Two was fought with a wide variety of weapons from all countries that fought in the conflict. As the war progressed, new and more deadly weapons were deployed on the world's battlefields.

Allied bombing of Germany

As distasteful as these bombing campaigns are today to most citizens of the liberal democracies under sixty years of age, the Combined Bomber Offensive in Europe and the bombing of Japan reflected not only a sense of moral conviction on the part of the West but a belief that such air attacks would end a war that daily grew more horrible for soldiers and civilians alike.

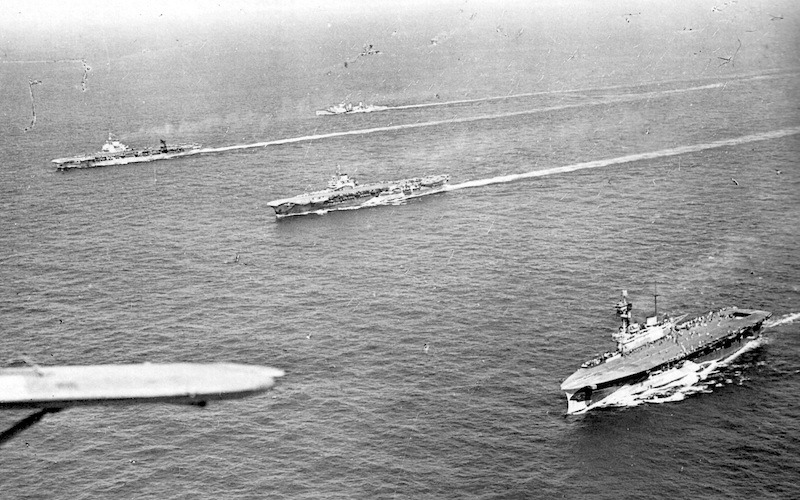

War at Sea during Word War II

The Allies eventually won the Battle of the Atlantic, but at a needlessly high cost. The armed forces’ lack of interest in anti-submarine warfare before the outbreak of the war was inexcusable, especially in light of their experiences in World War I. When Hitler invaded Russia Britain’s Prime Minister and America’s President supported URSS by establishing Arctic convoys of military equipment.

Asia after World War Two

World War Two fundamentally changed the destinies of China, Japan, Korea and South East Asia. Each country faced new challenges after the war, often as a direct consequence of the war, challenges that would shape their destinies for decades to come.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011