United States Home Front During World War I

American war mobilization

Although the United States had gone to war to defend democracy, in 1917 democracy did not extend to the right to oppose that war. America was torn by this and even more serious conflicts over the following months as the administration sought to reorganize the economy for war, raise and equip troops, and establish and enforce a patriotic fervor that would support the effort.

1 of 1

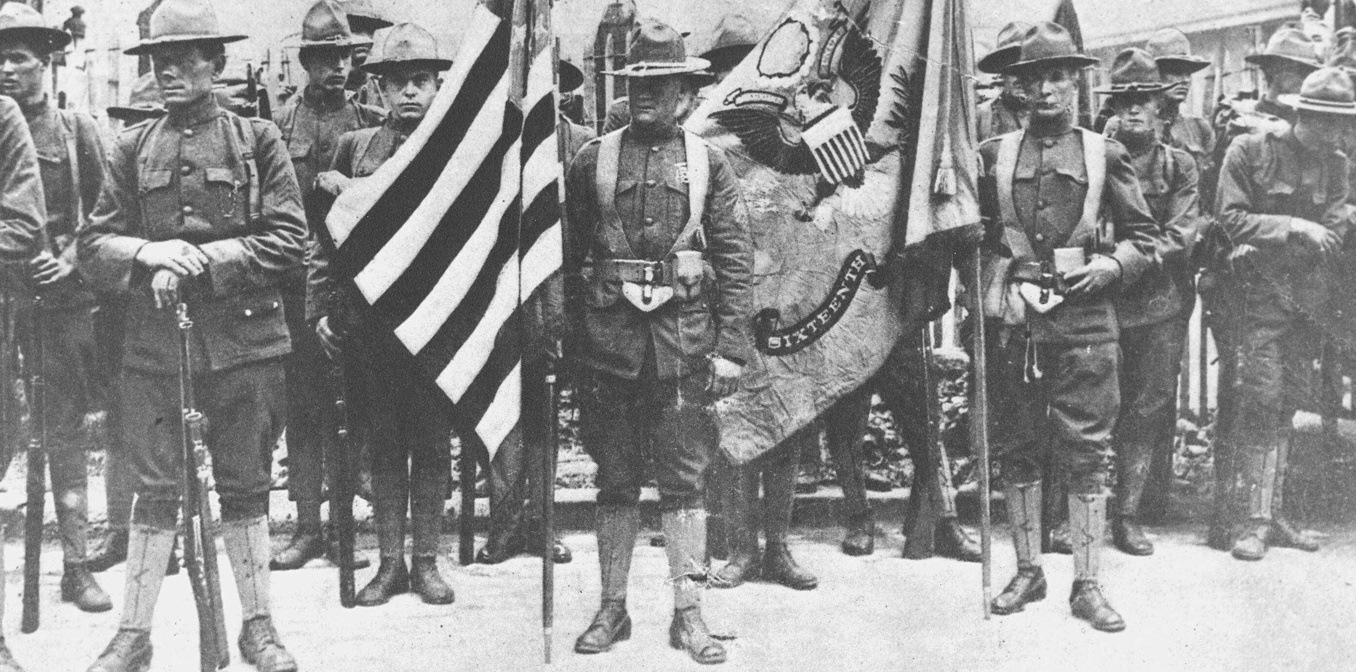

Although World War I raged in Europe, Asia, Africa, and on the oceans of the world for more than four terrible years, the United States participated in the war for only 19 months, from April 6, 1917, to November 11, 1918. Most American troops saw action only between February and November 1918.

Despite the brief engagement in the war and the relatively light casualties, the war had a deep and lasting impact on American society. The war marked the end of one era and the beginning of another. The deepest changes to American politics, economy, and society came about because of what transpired on the home front in the United States itself. When America declared war, its military forces were underprepared so they had to be organized and their numbers increased. Furthermore the US had to finance part of the French and British war effort, whose treasuries by 1917 were severely depleted.

1 of 3

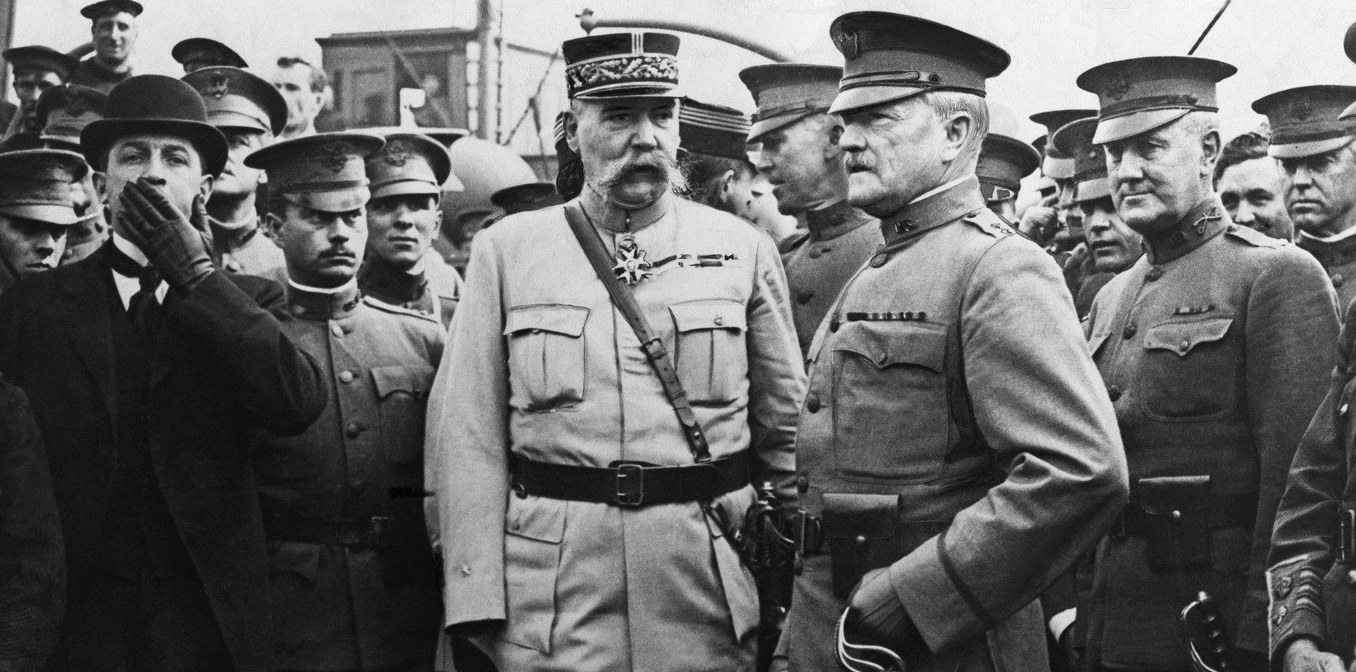

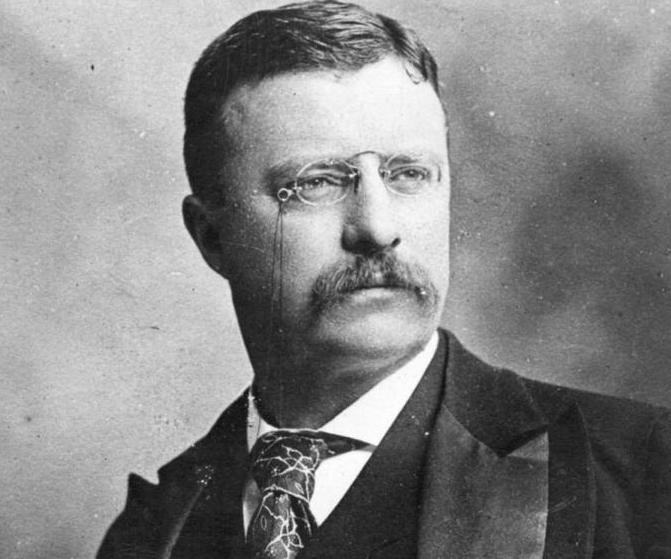

Until late 1916, President Wilson had resisted the cry for preparedness mounted by leaders who believed the United States should join the battle earlier, particularly men like Theodore Roosevelt and Walter Hines Page. Roosevelt, who had served as president from 1901 to 1909 and had run as a Progressive for the presidency in 1912 to lose to Wilson, had publicly complained about Wilson’s insistence on neutrality, openly charging that Wilson’s position constituted a form of cowardice.

2 of 3

Only reluctantly, facing reelection in 1916, had Wilson supported an expansion of the army and an increase in military budget. So when Wilson asked Congress for the declaration of war on the 2nd of April 1917, the nation had not really prepared for war, just as Roosevelt had warned. To build a fleet of ships and effective numbers of aircraft and to train and equip an army would, in most estimates, take at least two or three years.

3 of 3

The Entente had exhausted their credit, and so the US Treasury would be called upon to provide funding for British and French purchases of ammunition, food, fuel, weapons, and transport equipment. As a consequence, the US government’s problems were compounded in that it had to organize the nation’s industries to meet the demands of the Entente for a meaningful contribution to the war effort; it must organize and train an army, and also find a way to finance both the American and Entente efforts. Military and economic advisers viewed these tasks as daunting; even so, most believed that the American effort, once mounted, would eventually lead to a victory, probably in 1919 or 1920.

United States Neutrality in World War I

When war broke out in Europe in 1914 the US proclaimed a state of neutrality. Economically the US started to favor the British and their Allies. When Germany resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare America entered the war.

United States Entry Into the Great War

The American path to World War I is a long one, mired with political, economic and social complexities. At the star of the war the vast majority of Americans supported neutrality, not wanting to participate in what seemed a purely European war. By the beginning of 1917 the political and social climate in the United States was such that it allowed President Woodrow Wilson to declare war against Germany.

The American Expeditionary Force of World War I

US declared war against Germany but its army was small so any immediate American contributions for the war effort were of a naval and economic nature. By the summer of 1918 the Americans arrived in large numbers and played a key role in stopping the German advance towards Paris. The AEF had a decisive contribution in the war.

- Rodney P. Carlisle, World War I, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007

- Donald M. Goldstein, Harry J. Maihafer, America in World War I: The Story and Photographs, Brassey’s, Inc., Washington, D.C., 2004