United States Entry Into the Great War

American path from neutrality to joining the war against the Central Powers

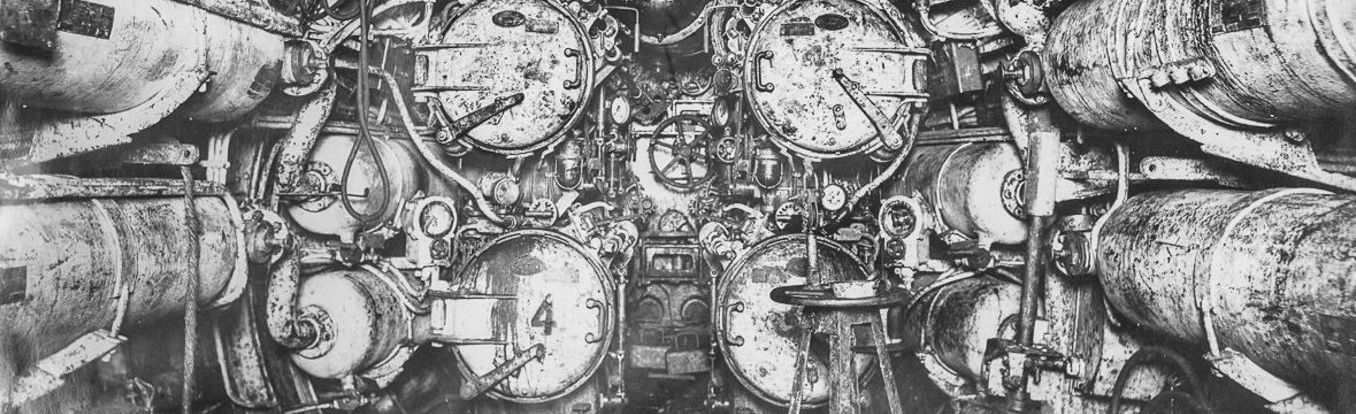

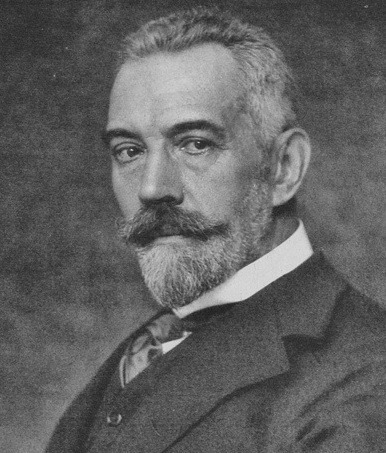

As part of the naval blockade of Germany, the British declared the North Sea a military area. From the outset, Theobald Bethmann Hollweg, the German Chancellor, was concerned about the possible reaction of neutral America. But the combination of press agitation and naval frustration overbore him, and on 4 February 1915 the Kaiser announced that the North Sea was a war zone and that all merchantmen, including neutral vessels, were liable to be sunk without warning. The US government immediately protested in the strongest terms.

1 of 3

Orders regarding the treatment of neutral vessels became ambiguous and the accusations directed by one belligerent against the other increasingly heated – and on the whole justified. The British flew neutral flags, and they armed merchant ships. If the U-boat captain obeyed international law he was liable to have his submarine attacked, particularly if he had fallen for one of the British decoys, the heavily armed but equally heavily disguised Q ships.

2 of 3

The breach of maritime law and its possible repercussions were recognized. The prevailing code required commerce raiders, whether surface or submarine, to stop merchant ships, allow the crew to take to the boats, provide them with food and water and assist their passage to the nearest landfall before destroying their vessel. The unrestricted policy allowed U-boat captains to sink by gunfire or torpedo at will.

3 of 3

The proponent of the unrestricted submarine warfare policy was Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff, chief of the German naval staff. His argument was that only through an all-out attack on British maritime supply could the war be brought to a favorable conclusion before blockade by sea and attrition on land exhausted Germany's capacity to continue the war. A similar argument was to be used by the German navy during the Second World War, when it instituted an unrestricted sinking policy from the start.

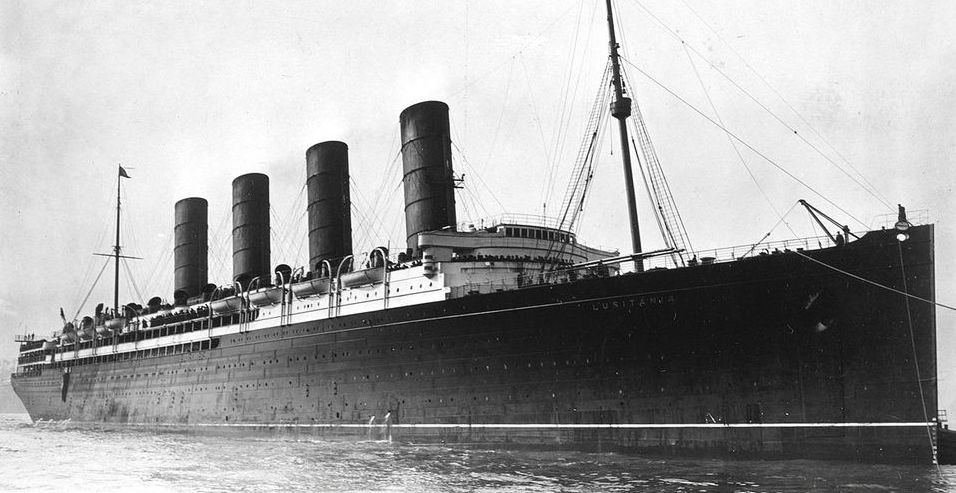

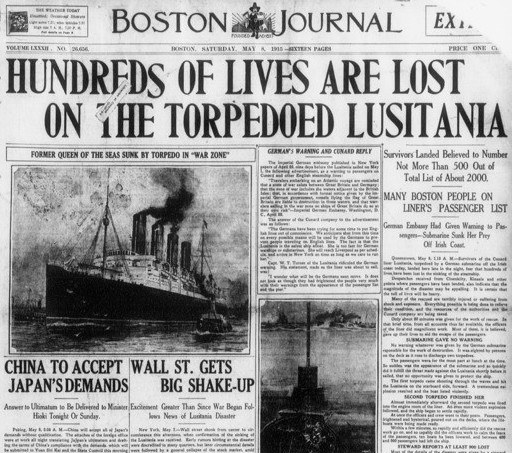

In terms of propaganda and diplomatic effect, the sinking of the Lusitania off the Irish coast on 7 May 1915 had a strong impact. She was indubitably a British-owned vessel, and as it happened she was carrying munitions. But she was principally a passenger ship, and among the 1,201 who died were many women and children, including 128 American citizens. President Woodrow Wilson, an academic and a Democrat, had been president since 1913. For the moment he held back from war. In doing so he reflected the views of most of his fellow citizens. After the incident the Germans temporarily suspended U-boat warfare.

1 of 5

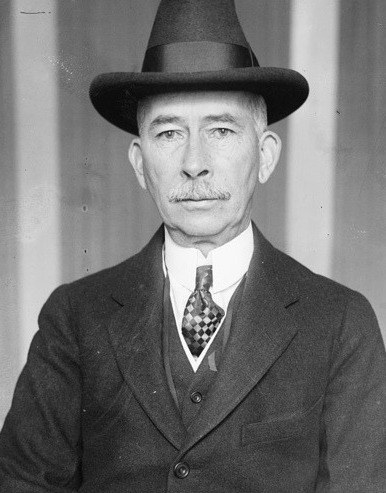

Colonel Edward House, plenipotentiary of Wilson, had crossed the Atlantic in the Cunard liner only weeks before and was about to sit down to a dinner in London organized by the American ambassador when the news came. House telegrammed the president to say that ‘America has come to the parting of the ways, when she must determine whether she stands for civilized or uncivilized warfare. We can no longer remain neutral spectators. Our action in this crisis will determine the part we will play when peace is made, and how far we may influence a settlement for the lasting good of humanity. We are being weighed in the balance, and our position among nations is being assessed by mankind.’

2 of 5

In Germany itself, the incident inclined both Bethmann Hollweg and the Kaiser’s circle in favor of operating under cruiser rules once more. By September 1915 the constraints on the U-boat commanders imposed by the Kaiser, as well as the internal friction they were generating within the navy itself, were sufficient to persuade the naval staff to suspend U-boat warfare.

3 of 5

Germany responded officially, noting that the Lusitania had carried ammunition and war cargo. The German press claimed that Britain had used civilians as human shields to protect such cargoes. Wilson regarded the response as evading the central issue of the right to travel on the high seas.

4 of 5

The Lusitania tragedy created such a newsworthy sensation that, for a generation, Americans remembered it, mistakenly, as one of the major causes of American entry into the war. In fact, the strong American protests over the Lusitania sinking resulted in a change in German policy and in a gradual improvement in German-American relations over the issue of sea transport during the following months.

5 of 5

Despite the popular outcry over the loss of American lives and of the lives of more than 1,000 other civilians aboard the Lusitania, Wilson delivered an appeal for calm in a speech in Philadelphia in May 1915, in which he pointed out ‘There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight.’ Cartoonists and critics immediately used the speech to suggest that Wilson lacked the spine to defend American rights.

United States Home Front During World War I

United States started mobilizing its huge industrial and potential prowess toward war production. Soldiers were conscripted through a draft lottery and those who were not sent to the front lines were put to work in factories. The American government initiated a propaganda campaign in order to gather support for the war effort.

United States Neutrality in World War I

When war broke out in Europe in 1914 the US proclaimed a state of neutrality. Economically the US started to favor the British and their Allies. When Germany resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare America entered the war.

The American Expeditionary Force of World War I

US declared war against Germany but its army was small so any immediate American contributions for the war effort were of a naval and economic nature. By the summer of 1918 the Americans arrived in large numbers and played a key role in stopping the German advance towards Paris. The AEF had a decisive contribution in the war.

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003

- Rodney P. Carlisle, World War I, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007

- Edward M Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, 1998

- Donald M. Goldstein, Harry J. Maihafer, America in World War I: The Story and Photographs, Brassey’s, Inc., Washington, D.C., 2004