The American Expeditionary Force of World War I

American forces in Europe

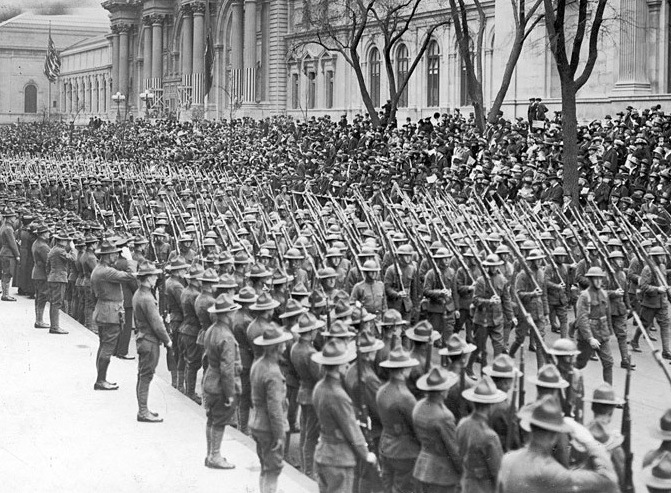

The United States was at war on 6 April 1917. What this meant, no one knew. Before the American government could answer the inevitable question of the extent of its contribution to the war effort, it had to determine its military capacity as well as the actual situation and the needs of its co-belligerents. In their conferences with American officials, the British and French dignitaries described the disheartening war situation and pled for ships and money. French Marshal Joseph Joffre also requested that the US send troops to France. President Woodrow Wilson approved a division to be sent to France immediately.

1 of 6

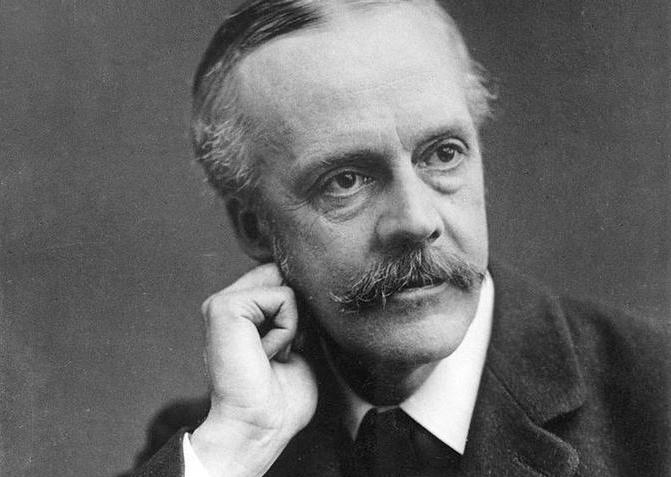

The British mission came first. With the distinguished philosopher-statesman, former Prime Minister and current Foreign Secretary Arthur J. Balfour at its head, this group of experts commanded respect.

2 of 6

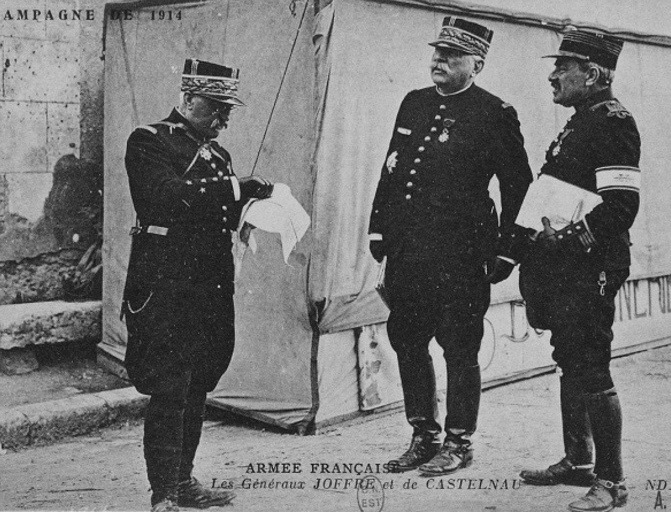

Although former Premier René Viviani led the French delegation, American eyes and hearts focused on the massive figure of Marshal Joseph Joffre. Throughout his stay the nation gave the Hero of the Marne the enthusiastic welcome usually reserved for its own heroes.

3 of 6

In public speeches Joffre was brief and bland, but in private conversations he made his points forcefully. After a disappointing, vague speech to the students of the Army War College, Joffre retired to the college president's office where he spelled out his advice to the nation's key military leaders.

4 of 6

Newton D. Baker, the Secretary of War, Major Generals Hugh L. Scott and Tasker H. Bliss, the Chief of Staff and Assistant Chief of Staff respectively, listened attentively as Joffre talked through an interpreter. First, he advised them to send a division to France as soon as possible. Then, the Entente immediately needed technical forces such as transportation troops. He also impressed upon them the necessity for beginning at once to organize and train a large army. This should be maintained as an independent American army.

5 of 6

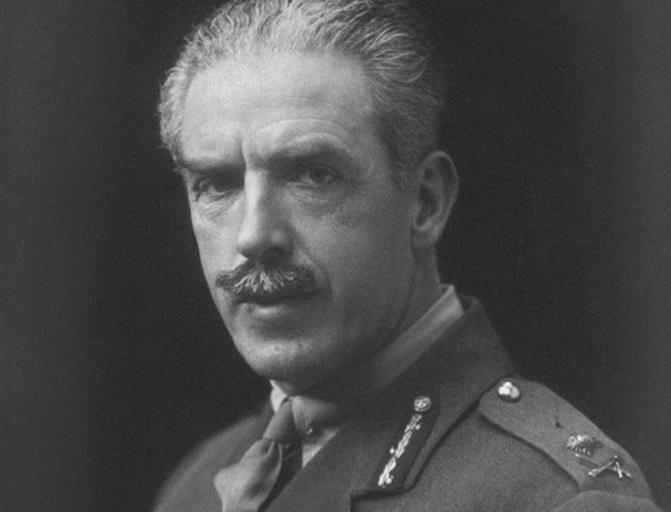

The British joined their ally in advocating a ‘show the flag’ contingent and in requesting technical troops. But Major General G. T. M. ‘Tom’ Bridges, a former combat division commander, struck a discordant note when he suggested that his army be allowed to recruit Americans into its units. Although Joffre had been more diplomatic in his counsel of an independent force, other French officers basically agreed with Bridges.

6 of 6

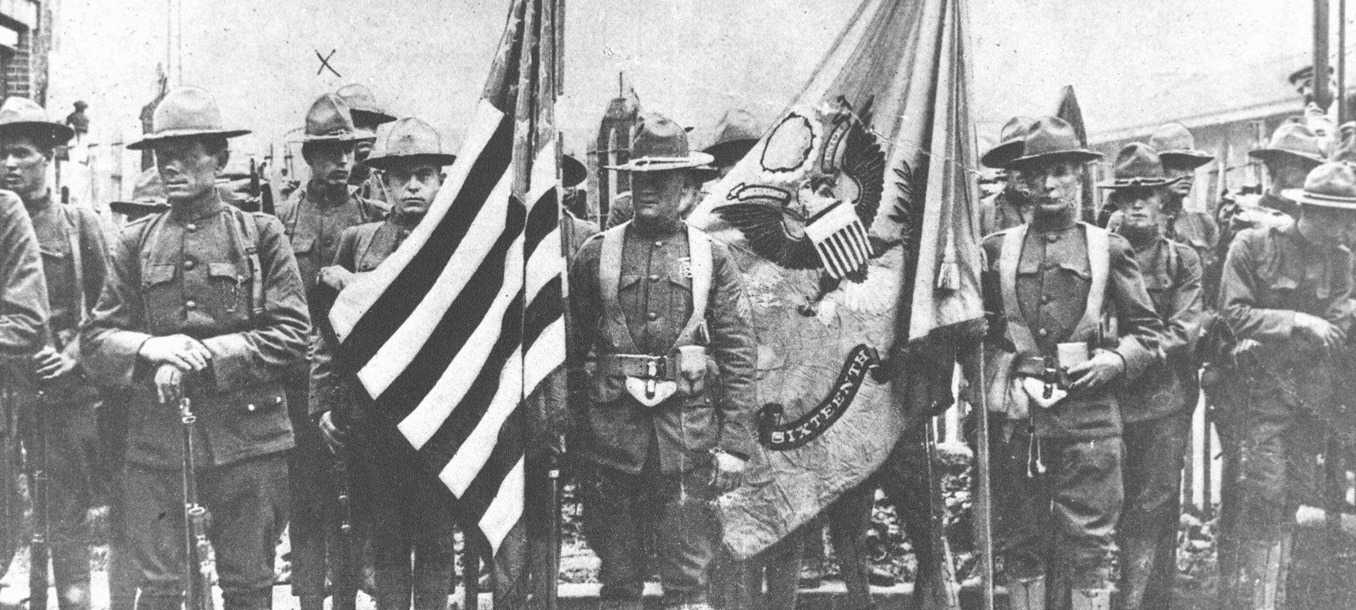

At this stage, few realized the vast difference between a willingness to fight and an ability to do so. Actually the country was ill prepared militarily, both in trained manpower and equipment. Americans traditionally had opposed a large standing army, viewing such a thing almost with suspicion. Among the world’s armies, the US ranked sixteenth in size, just behind Portugal. The United States had no tanks, its fifty or so planes were nearly obsolete, and its heavy guns had ammunition enough for only a nine-hour bombardment.

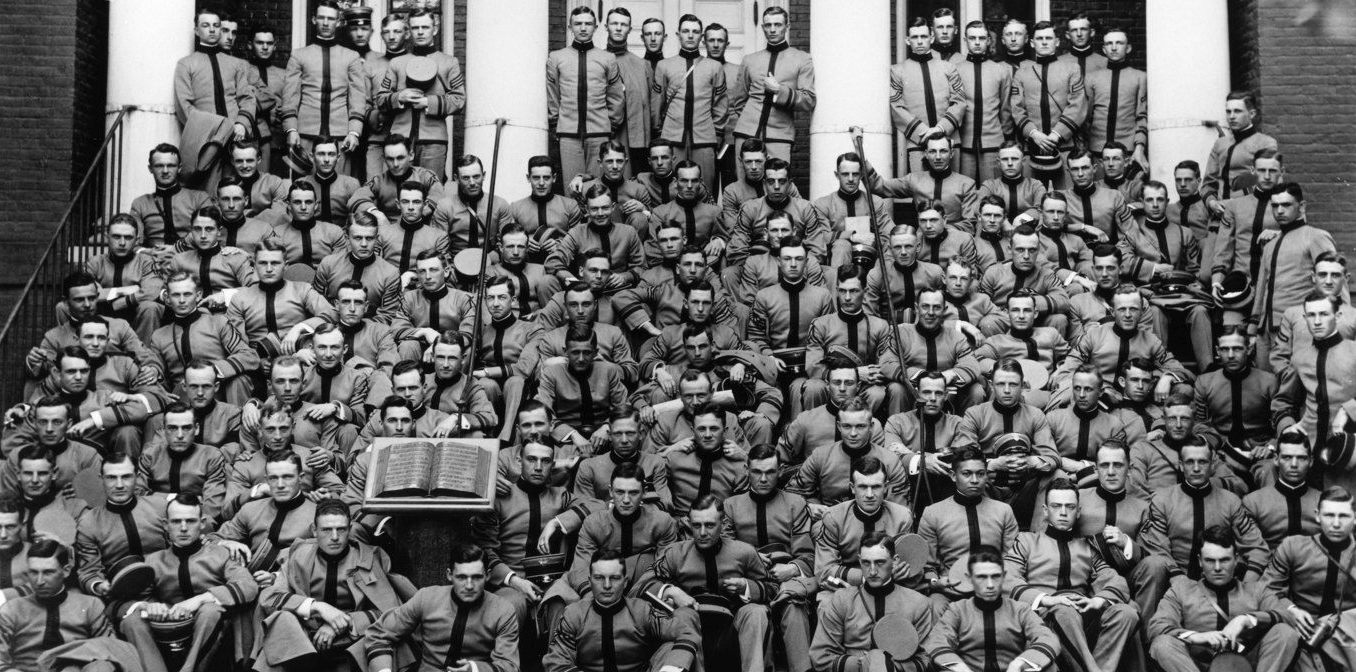

Although the American army was not impressive by European standards, it had undergone basic reforms during the first decade of the century. In a period bridging the McKinley and Roosevelt administrations, Secretary of War Elihu Root, a New York corporation lawyer, laid the foundation for a modern army. As late as 1917, however, young, progressive officers and some of their elders recognized that they had to struggle to maintain advances in the areas of professional education, the general staff concept, and the relationship between the National Guard and the regular army.

1 of 6

As the nucleus of his reforms, Root emphasized increased training for officers. With the establishment of the Army War College and the revitalization of various other schools, he provided the necessary educational advantages. In particular the courses at Fort Leavenworth's School of the Line and Staff College stimulated a generation of professionals.

2 of 6

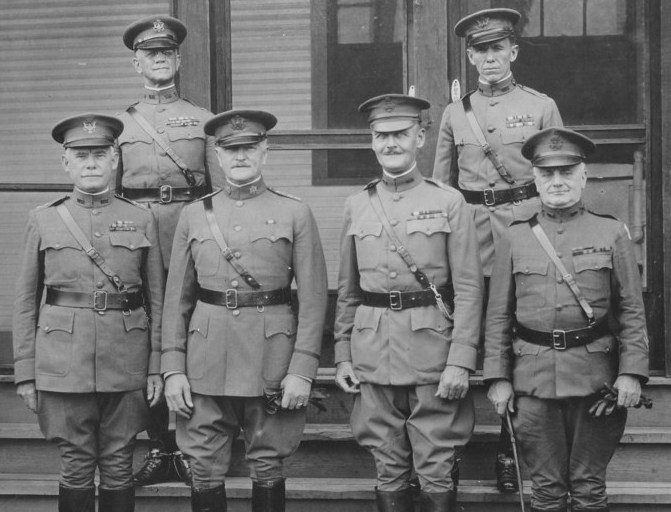

At Fort Leavenworth young officers and, by correspondence, some older ones such as Brigadier General John J. Pershing, solved tactical problems with the help of German textbooks and topographical maps. At the time it appeared ridiculous to pore over maps of the Metz area. A few years later, when some of these officers were routing troops into that area, it seemed ironical.

3 of 6

To supplement their training, a few officers had the opportunity of visiting and observing foreign armies. During the Russo-Japanese War, American military observers included Pershing and the future Chief of Staff, Peyton C. March, as well as the man who would head the wartime draft, Enoch H. Crowder, and a junior lieutenant, Douglas MacArthur.

4 of 6

In 1912, a group of Leavenworth graduates, including George Van Horn Moseley and John McAuley Palmer, saw first-hand the German, French, and English armies. Others, among them Captain Fox Conner, served in French units. On their next visit to Europe, most of these men would occupy key positions on the American Expeditionary Forces staffs. These officers in 1918 represented the harvest of the Root education system.

5 of 6

Throughout the army's existence, the lack of a coordinating agency had hindered it. Although a commanding general existed in name, he was limited in fact by the chiefs of the various service bureaus in the War Department. A general staff needed to be established, composed of officers from all branches of the service, which would study army problems as a whole and make recommendations to a Chief of Staff who then would pass them on to the Secretary. Root persuaded Congress to create such an organization.

6 of 6

Since colonial times, the American military system had been based on the availability and adequacy of civilians to meet any defense need. Over the years, the militia had repeatedly demonstrated its vulnerability on both counts. Root attempted to make this legendary bulwark of defense more effective by introducing a much closer relationship between the militiamen and the regulars in the form of joint maneuvers and federal inspections as well as by increased standardization of the state-controlled units. This program worked to the mutual advantage of the militia and the army.

United States Home Front During World War I

United States started mobilizing its huge industrial and potential prowess toward war production. Soldiers were conscripted through a draft lottery and those who were not sent to the front lines were put to work in factories. The American government initiated a propaganda campaign in order to gather support for the war effort.

United States Neutrality in World War I

When war broke out in Europe in 1914 the US proclaimed a state of neutrality. Economically the US started to favor the British and their Allies. When Germany resumed its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare America entered the war.

United States Entry Into the Great War

The American path to World War I is a long one, mired with political, economic and social complexities. At the star of the war the vast majority of Americans supported neutrality, not wanting to participate in what seemed a purely European war. By the beginning of 1917 the political and social climate in the United States was such that it allowed President Woodrow Wilson to declare war against Germany.

- Rodney P. Carlisle, World War I, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007

- Edward M Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, 1998

- Donald M. Goldstein, Harry J. Maihafer, America in World War I: The Story and Photographs, Brassey’s, Inc., Washington, D.C., 2004