The War at Sea in 1918

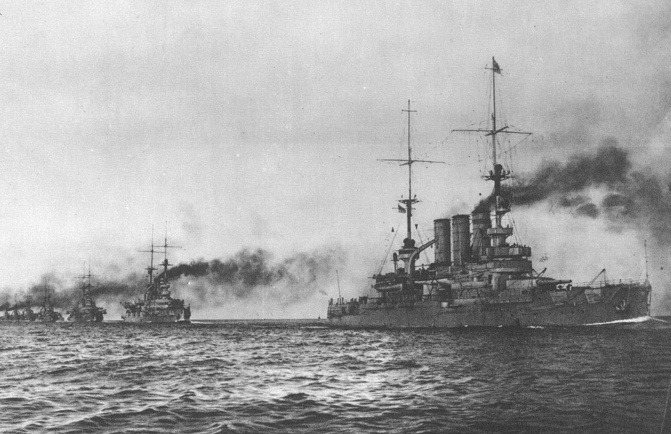

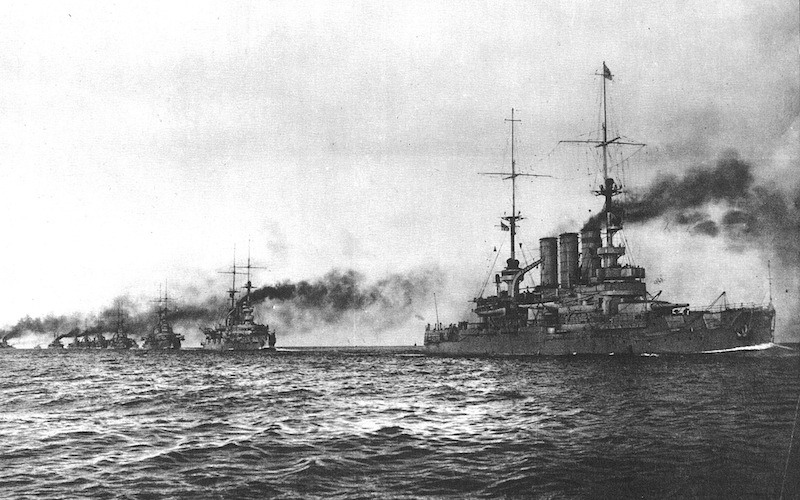

Defeat of the German High Seas Fleet

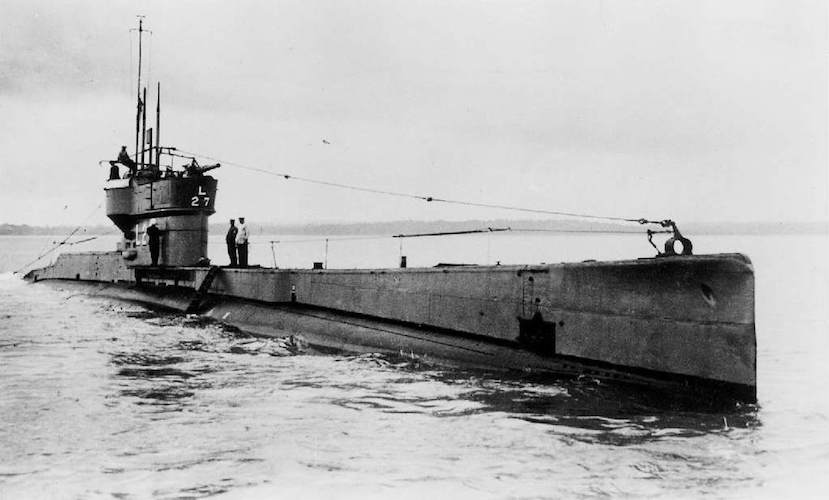

By 1918, the rate of Entente tonnage sunk per German submarine lost had fallen. Nevertheless, the Germans continued to inflict damage on Entente supply lines. The hard work of convoying under continual threat of submarine attack continued until the end of the war. German surface ships had far less impact, other than in diverting enemy resources.

1 of 4

The arrival in France of American troops and matériel made the strategic irrelevance of the German navy in 1918 abundantly clear, although it always remained a fleet-in-being fixing the Grand Fleet. Moreover, American entry into the war made any idea of a decisive German naval sortie less credible, while also leading to the buildup of American troops in France, which further limited German options.

2 of 4

In the face of the clear Entente superiority, a decisive German naval sortie was less credible. The German surface fleet languished, while its men became seriously discontented, leading to their mutiny at the end of the war.

3 of 4

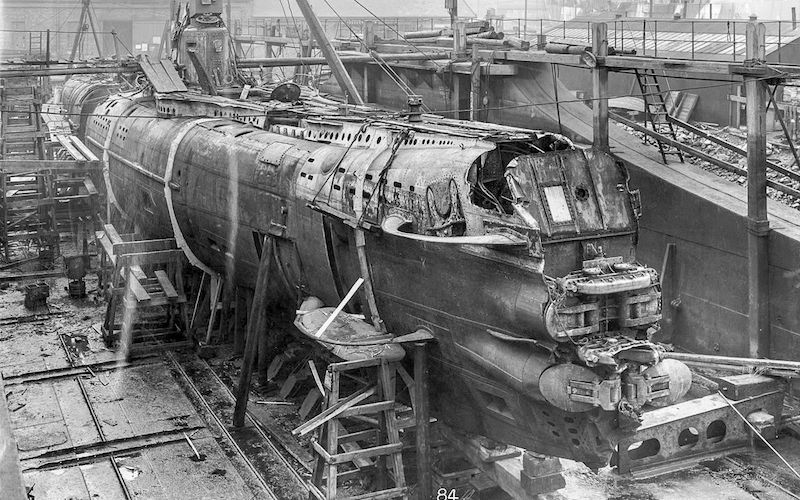

A bold but over-optimistic operation was planned by Commodore Sir Roger Keyes to block the exits from German submarine pens in occupied Belgium. The main effort was focused on Zeebrugge. The plan was to scuttle three blockships loaded with concrete in the mouth of the Bruges Canal which linked the U-boat pens to the sea. The approach to the canal was protected by batteries on Zeebrugge mole, a stone breakwater. These were to be disabled by a party of seamen and Marines landed on the mole by the cruiser Vindictive and two modified ferries.

4 of 4

The attack at Zeebrugge went badly from the start. Vindictive was battered by gunfire and ran against the mole in the wrong place. The landing party could not take the batteries, making it hard for the blockships to reach the canal entrance. With heroic effort two of them were scuttled as planned, but one sank short of its target. The raid was immensely popular in Britain. Keyes was knighted and 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded. But it cost 214 lives and failed to significantly inhibit U-boat operations.

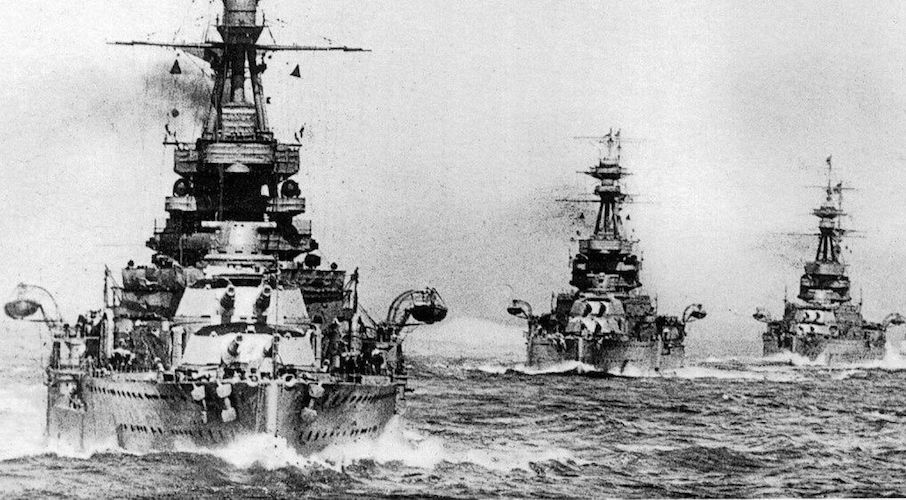

By 1918, the Americans were firmly welded into the Grand Fleet which would move south to Rosyth, in the Firth of Forth, at Admiral David Beatty’s instigation in April 1918. The Americans contributed the five fast dreadnoughts of the 6th Battle Squadron, under the command of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, which were soon integrated into the fleet.

1 of 1

Rodman showed a refreshing willingness to conform to British methods of tactics, gunnery and signals, recognizing the value of the long years of war experience possessed by the Royal Navy. This stood in sharp contrast to the attitude adopted by General John Pershing and the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front, who ignored the advice of British and French commanders at every turn.

The War at Sea: The first battles

During the Great War naval power was crucial even though there were no decisive battles. In the beginning the British retained essential control of their home waters and were able to avoid blockade and serious attack. Nevertheless, German warships bombarded English east coast towns, notably Hartlepool, Scarborough, and Whitby causing great popular outrage by doing so.

The War at Sea in 1915

In 1915 the British blockade of Germany was fully implemented by the Grand Fleet. To counter the blockade the Germans launched a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, meaning that any ships around Britain, enemy or neutral, would be sunk.

The War at Sea in 1916

During 1916 the German fleet sought again to implement its plan to attack the British in a major battle in an effort to weak the British Grand Fleet in a decisive manner. The plan led to the Battle of Jutland. The British did not fall for the German plan, however, despite having the larger fleet at Jutland, they failed to achieve the sweeping victory hoped by the Navy as well as the British public.

The War at Sea in 1917

During 1917 Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in an effort to stop the flow of supplies towards Britain. The attempt backfired when US President Woodrow Wilson declared war against Germany.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Jeremy Black, Naval Warfare: A Global History since 1860, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland, 2017

- R.G. Grant, Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing, London, 2011