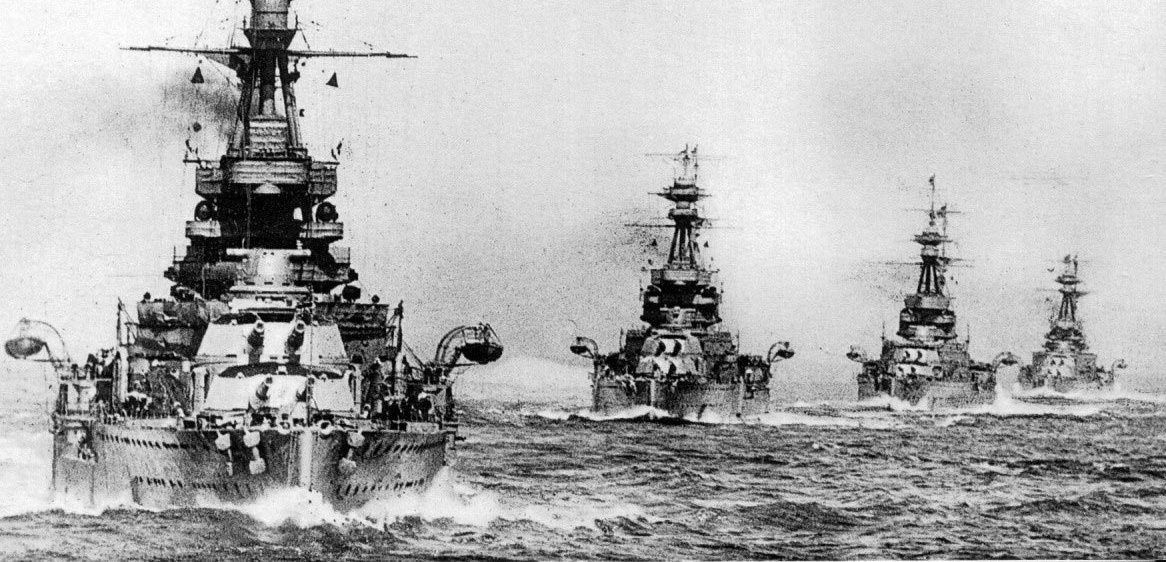

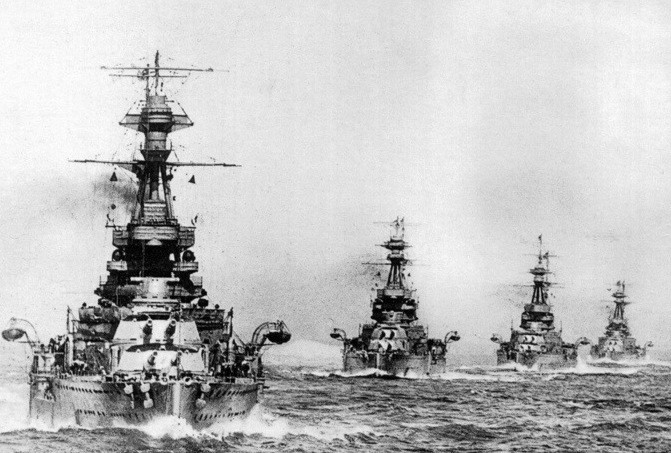

The War at Sea in 1916

Naval stalemate at the Battle of Jutland

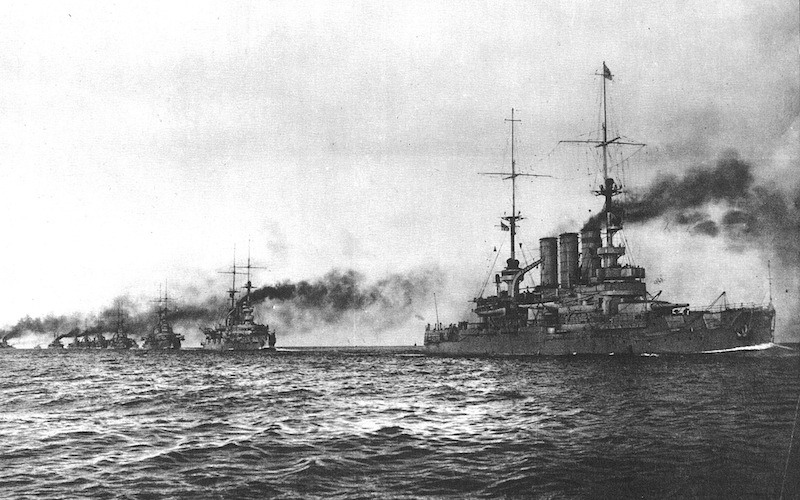

In 1916, the Germans once again sought to implement their plan to fall upon part of the British Grand Fleet with their entire High Seas Fleet. This plan led to the Battle of Jutland. With a reasonable grasp of the operational and strategic situation, the British did not fall for the German plan. Nevertheless, despite having the larger fleet at Jutland, they failed to achieve the sweeping victory hoped for by naval planners and the public.

1 of 3

At Jutland the British suffered seriously from problems with fire control, inadequate armor protection, especially on the battle cruisers, the unsafe handling of powder in dangerous magazine practices that were an effort to compensate for the poor gunnery of the battle cruisers, poor signaling, and inadequate training, for example in destroyer torpedo attacks and in night fighting.

2 of 3

For the Royal Navy, there was a general problem of underperformance. German gunnery at Jutland was superior to that of the Royal Navy (ie more accurate), partly because of better optics and better fusing of the shells, and partly because of the advantages of position, notably the direction of light. The Germans were far less visible to opposing fire, and their range firing was therefore easier.

3 of 3

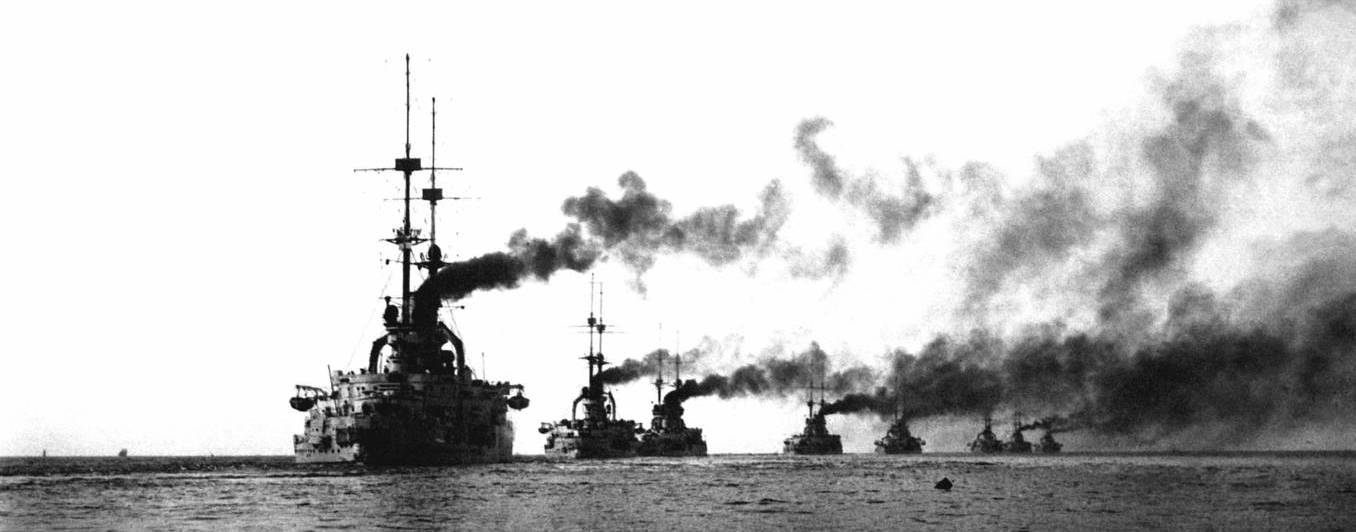

The British employed their fleet by deterring the Germans from acting and thus challenging the British blockade or use of the sea. This deterrence thwarted the optimistic German plan of combining surface sorties with submarine ambushes in order to reduce the British advantage in warship numbers, a plan for attrition that was difficult to implement. This advantage was supplemented by British superiority in the intelligence war, especially the use of signals intelligence. The location of German warships was generally known by the British.

In January 1916 the state of the war changed with the dismissal of the ineffective German Admiral Hugo von Pohl as commander of the German High Seas Fleet. He was replaced by the far more dynamic Admiral Reinhard Scheer. The fleet had spent most of 1915 in harbor maintaining its status as a ‘fleet in being’ not to be risked in action, while the U-boats had been withdrawn from the Atlantic Ocean and the English Channel. This had allowed the Royal Navy to exert an almost unchallenged domination of the oceans. Scheer was determined to find a fit and proper role for the High Seas Fleet.

1 of 1

Born in Obernkirchen, Hanover, Scheer joined the Imperial German Navy in 1879. By 1907 he had risen to be Chief of Staff of the High Seas Fleet. On the outbreak of World War I he advocated the use of surface ships to lure British warships into the path of submarines lying in ambush. On being promoted to Admiral of the Fleet, he used a similar tactic at Jutland. The skill of his maneuvers in the battle enabled the German fleet to escape and even to claim victory.

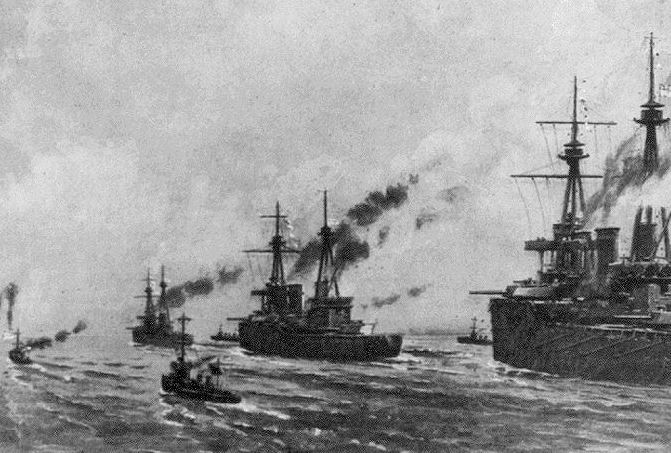

The War at Sea: The first battles

During the Great War naval power was crucial even though there were no decisive battles. In the beginning the British retained essential control of their home waters and were able to avoid blockade and serious attack. Nevertheless, German warships bombarded English east coast towns, notably Hartlepool, Scarborough, and Whitby causing great popular outrage by doing so.

The War at Sea in 1915

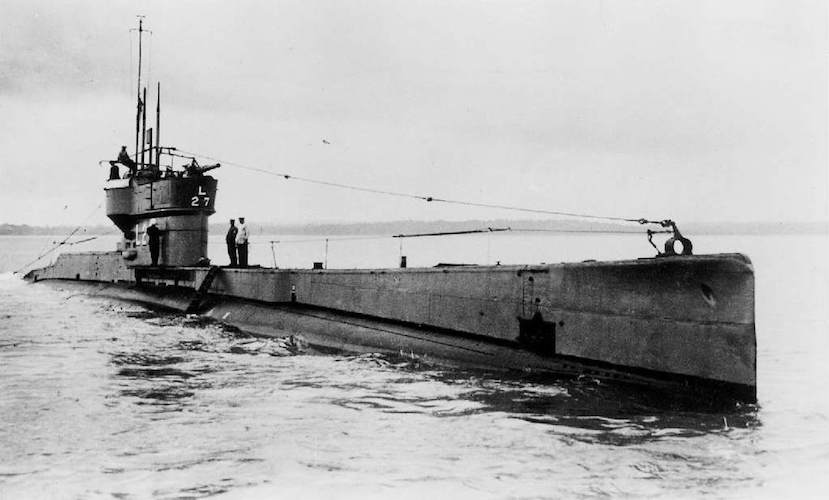

In 1915 the British blockade of Germany was fully implemented by the Grand Fleet. To counter the blockade the Germans launched a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, meaning that any ships around Britain, enemy or neutral, would be sunk.

The War at Sea in 1917

During 1917 Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in an effort to stop the flow of supplies towards Britain. The attempt backfired when US President Woodrow Wilson declared war against Germany.

The War at Sea in 1918

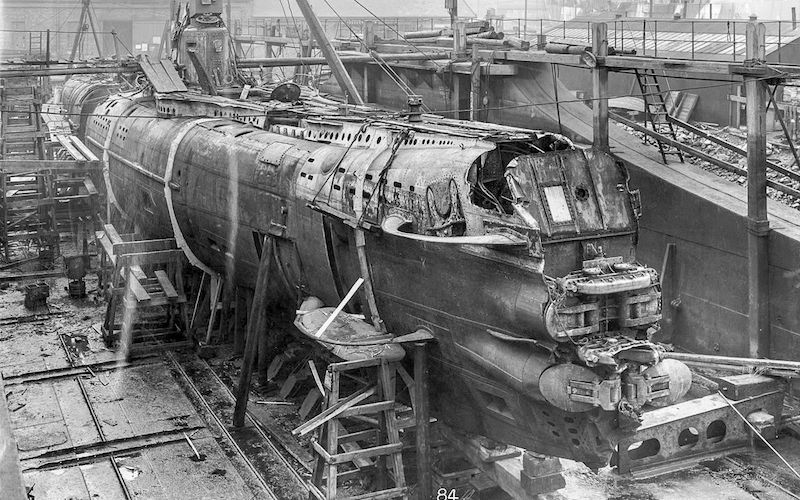

By 1918 the Entente convoy system was very well established and German submarines were hunted down with great efficiency. On the surface few engagements to place, the most notably being the British raid at Zeebrugge. The war ended with the German fleet being disbanded after the sailors mutinied at Kiel.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Jeremy Black, Naval Warfare: A Global History since 1860, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland, 2017

- R.G. Grant, Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing, London, 2011