The War at Sea in 1917

The U-boat war escalates. The US enters the war

Having failed in 1916 to drive France from the war at the Battle of Verdun (on land), and the British at Jutland, and having, in turn, experienced the lengthy and damaging British attack in the Somme offensive (on land), in 1917 the Germans sought to force Britain from the war by resuming attempts to destroy its supply system. Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed with one major consequence: the United States declared war against Germany. By the end of the year, the British managed to contain the German submarine threat by implementing a convoy system.

1 of 5

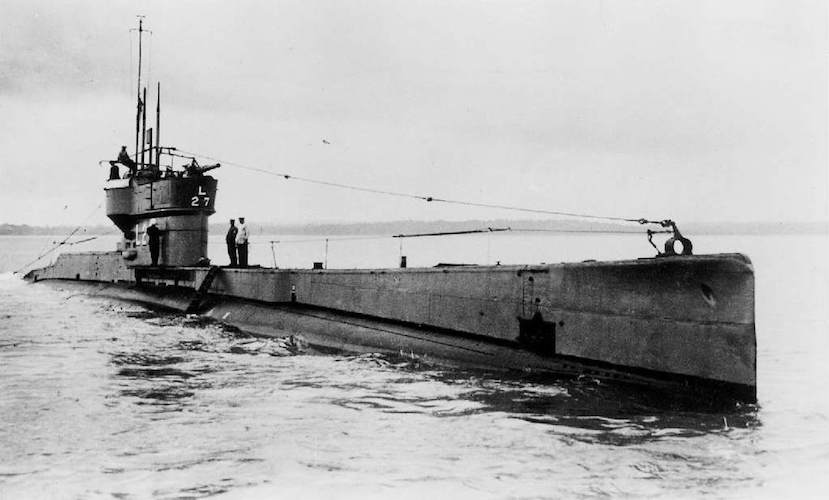

The seeds were set for unrestricted submarine warfare; yet this would be a gamble based on the lack of a realistic alternative rather than the inherent merits of the policy. German naval experts believed that they could knock Britain out of the war if they managed to sink some 600,000 tons of shipping a month for just five months. The British would simply run out of shipping while neutral shipping would either be frightened away or be sunk itself.

2 of 5

Ironically, America’s entry into the war increased the importance of submarines to German capability, since it increased the number of surface warships pitted against Germany. This prefigured the situation in 1941, when the United States entered the Second World War against Germany, although then the German surface fleet was relatively weaker.

3 of 5

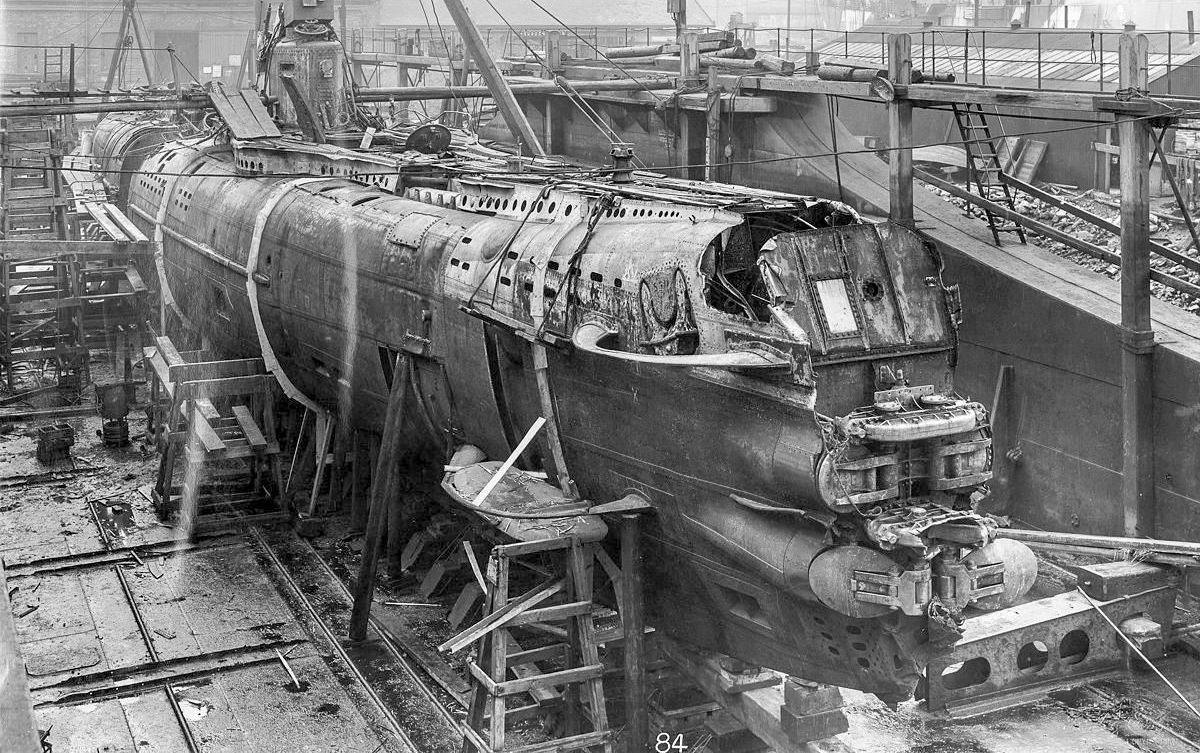

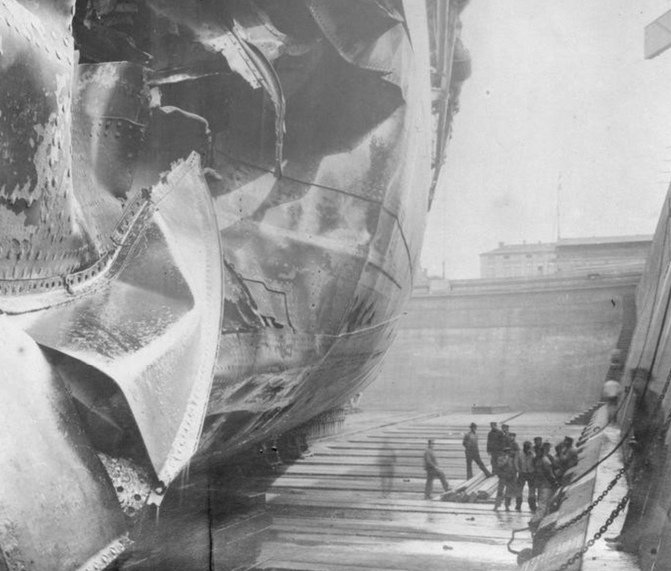

The initial rate of Entente shipping losses was sufficiently high to threaten defeat. Serious losses were inflicted, especially on British commerce, in large part due to British inexperience in confronting submarine attacks. The limited effectiveness of anti-submarine weaponry was also an issue, as depth charges, another new technology, were effective only if they exploded close to the hull of the submarine. This was also a period when effective artillery techniques on land were still being worked out. It took time to establish and disseminate such techniques.

4 of 5

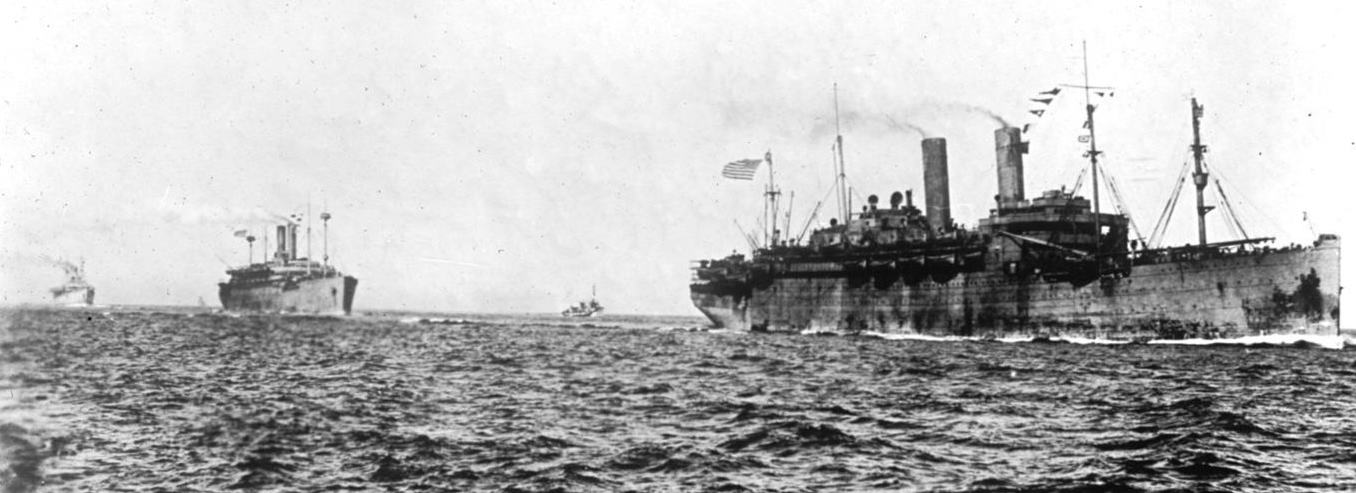

In the event, as later in the Second World War, Britain survived the onslaught, by fighting and defeating the submarines and also due to success on the home front. The introduction in May of a system of escorted convoys cut shipping losses dramatically and helped lead to an increase in the sinking of submarines.

5 of 5

Convoys were also resisted by certain naval circles as not being sufficiently in line with the bold ‘Nelson touch’, which they believed necessary and appropriate. To look after convoys was not the role of warriors. Nineteenth-century Royal Navy culture had blurred the success of convoys in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars from 1793 to 1815. However, against a background of resource superiority and a degree of naval control that enabled them to choose from different options, the Admiralty eventually took the necessary steps.

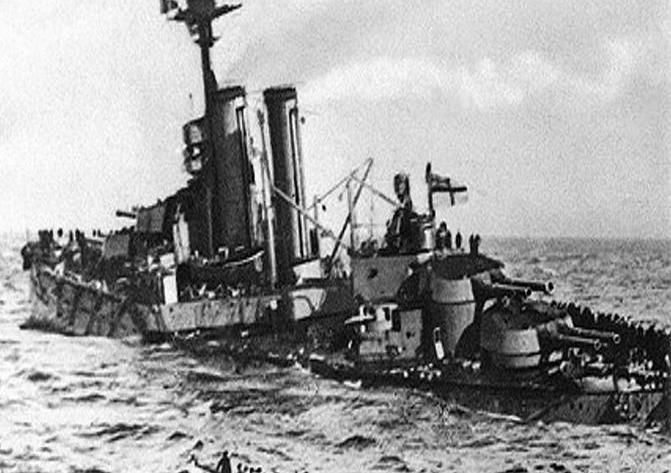

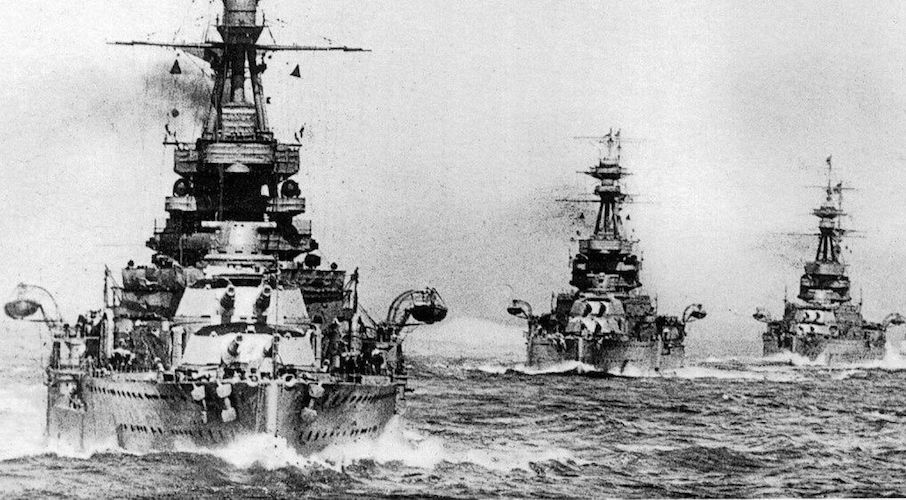

After the first fleet action in the dreadnought age, it is not surprising that there were a great number of technical and material considerations for the British to digest. One thing was evident: something had gone wrong with the battlecruisers, and a full investigation into their explosive demise was begun, resulting in strict anti-flash precautions being implemented, plus additional

armor protection for all those ships still under construction. But urgent improvements were also required in the design of British shells, which had shown a distinct tendency to break up on impact, thus not causing the anticipated damage.

1 of 2

Night fighting may still have been abhorred, but Jutland forced a belated recognition of the necessity for proper training and preparations. There was a general tightening of ship-to-ship identification procedures, searchlights with removable covers were fitted, and night exercises were begun in earnest.

2 of 2

The method of handling and disseminating naval intelligence was also improved to avoid the kind of errors which had dogged Jellicoe at Jutland. The British had certainly learned some valuable lessons from their bitter disappointment.

The War at Sea: The first battles

During the Great War naval power was crucial even though there were no decisive battles. In the beginning the British retained essential control of their home waters and were able to avoid blockade and serious attack. Nevertheless, German warships bombarded English east coast towns, notably Hartlepool, Scarborough, and Whitby causing great popular outrage by doing so.

The War at Sea in 1915

In 1915 the British blockade of Germany was fully implemented by the Grand Fleet. To counter the blockade the Germans launched a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, meaning that any ships around Britain, enemy or neutral, would be sunk.

The War at Sea in 1916

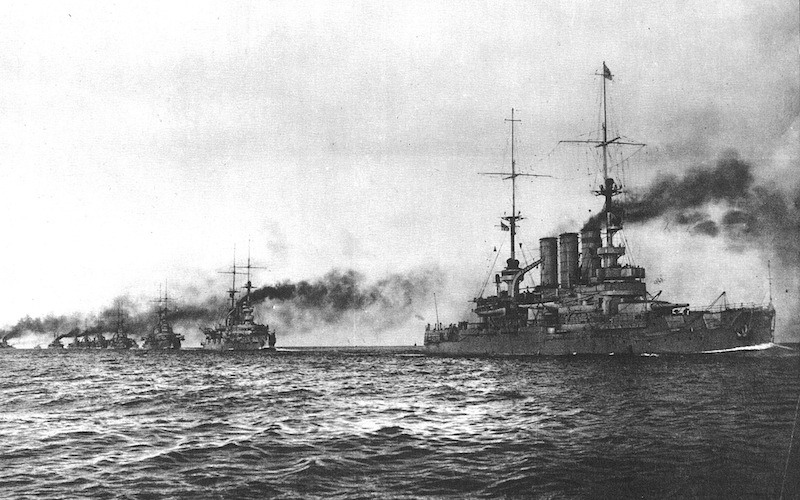

During 1916 the German fleet sought again to implement its plan to attack the British in a major battle in an effort to weak the British Grand Fleet in a decisive manner. The plan led to the Battle of Jutland. The British did not fall for the German plan, however, despite having the larger fleet at Jutland, they failed to achieve the sweeping victory hoped by the Navy as well as the British public.

The War at Sea in 1918

By 1918 the Entente convoy system was very well established and German submarines were hunted down with great efficiency. On the surface few engagements to place, the most notably being the British raid at Zeebrugge. The war ended with the German fleet being disbanded after the sailors mutinied at Kiel.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Jeremy Black, Naval Warfare: A Global History since 1860, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland, 2017

- R.G. Grant, Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing, London, 2011