The War at Sea in 1915

Submarine warfare escalates. British blockade of Germany

In 1915, although the Germans attacked at sea, their bold plan to fall upon part of the British Grand Fleet with their entire High Seas Fleet, and thus achieve a superiority that would enable them to inflict serious casualties, affecting the overall situation at sea, was not pursued.

1 of 4

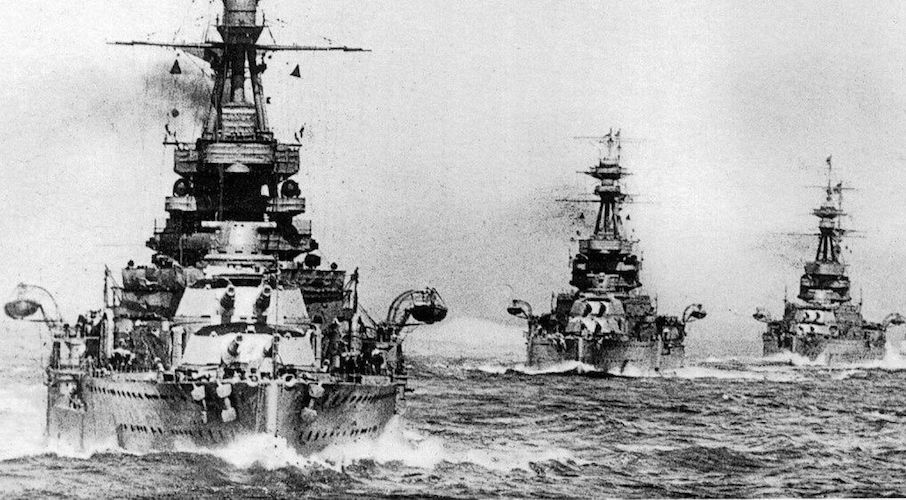

The British were affected by the contrast between the long range at which shells could be fired and their limited number of hits, while heavy smoke affected the optical range finding crucial to gunnery. Yet, alongside these disadvantages, the British Grand Fleet was becoming both absolutely and relatively stronger, with five newly operational dreadnoughts added to it in the winter of 1914-15.

2 of 4

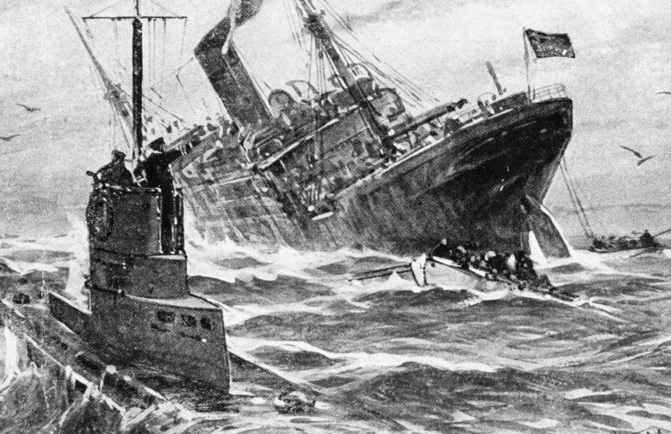

In 1915, Germany increased the threat and tempo of their assault on Entente shipping by declaring unrestricted submarine warfare. This policy entailed attacking all shipping without warning, Entente and neutral, within the designated zone.

3 of 4

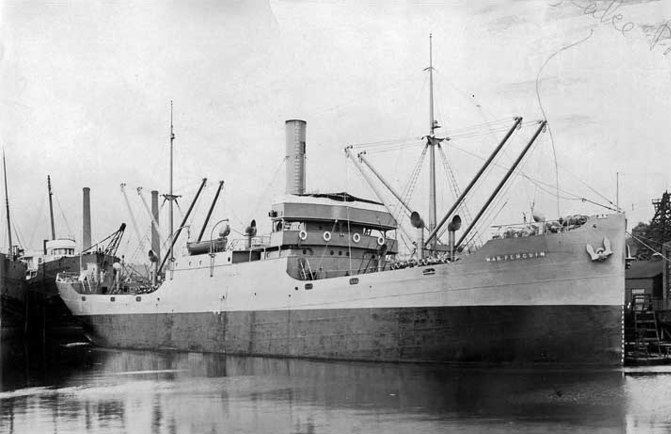

The Atlantic trading system on which the British economy rested, and which was a core component of its maritime position and power, was the prime target for German naval warfare by 1915. Trade played the key role in accumulating and mobilizing the capital and securing the matériel on which Entente war-making depended.

4 of 4

The Lusitania, the largest liner on the transatlantic run as well as a British ship, was sunk off Ireland by U-20. Among the 1,192 passengers and crew lost were 128 Americans, and there was savage criticism in America. In response, Germany offered concessions over the unrestricted warfare. It was finally cancelled in order to avoid provoking American intervention.

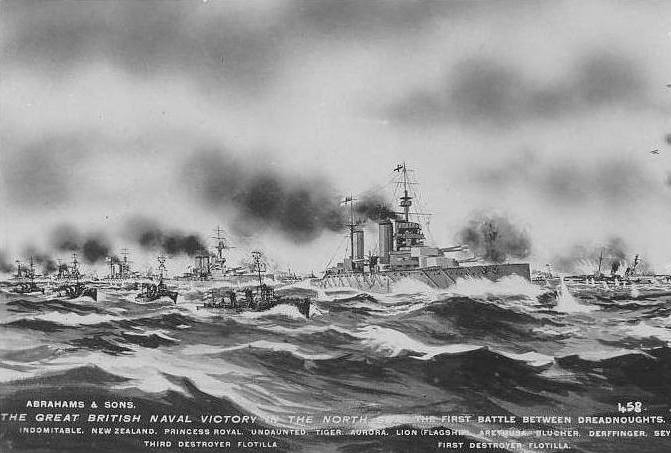

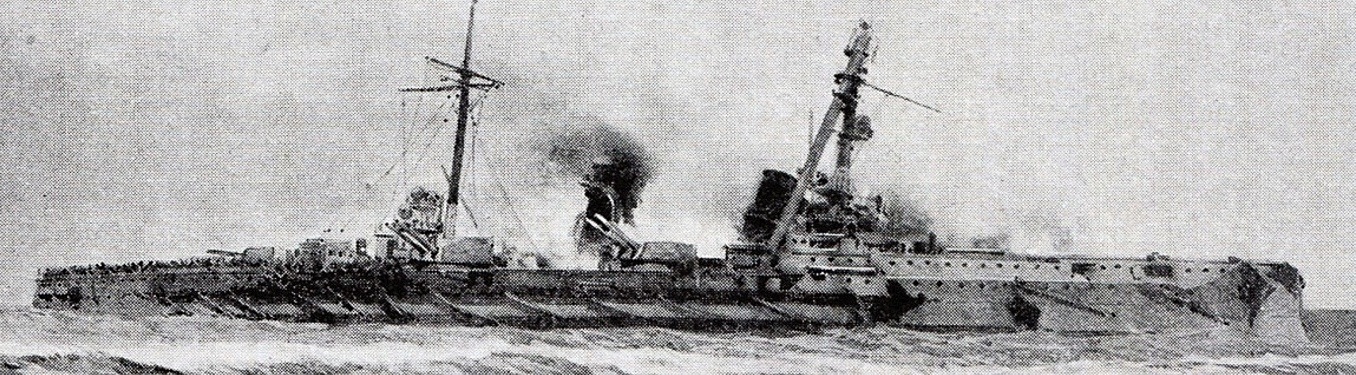

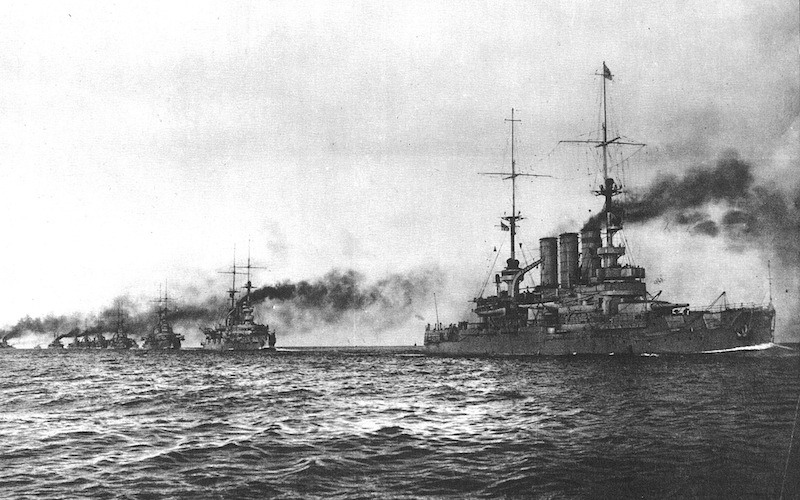

Admiral Franz von Hipper took the German 1st and 2nd Scouting Groups into the North Sea to attack British trawlers and patrol boats on the Dogger Bank. Intercepts by Royal Navy signals intelligence revealed the plans, and Admiral David Beatty was sent out with the 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons to surprise Hipper, joined by the light cruisers and destroyers of the Harwich Force. Once Hipper realized that heavy British ships were present, he turned for home. Beatty’s flagship Lion drew first blood. Four British battlecruisers poured shells into the crippled Blücher until she sank, while Hipper led his battlecruisers home to safety.

1 of 6

The intercepted signals did not make it clear what the Germans were about to do, so it was assumed that they were intent on another coastal raid. In fact Hipper was planning to entrap and destroy the British light forces operating in the Dogger Bank region but, as prior intelligence goes, it was still pure gold.

2 of 6

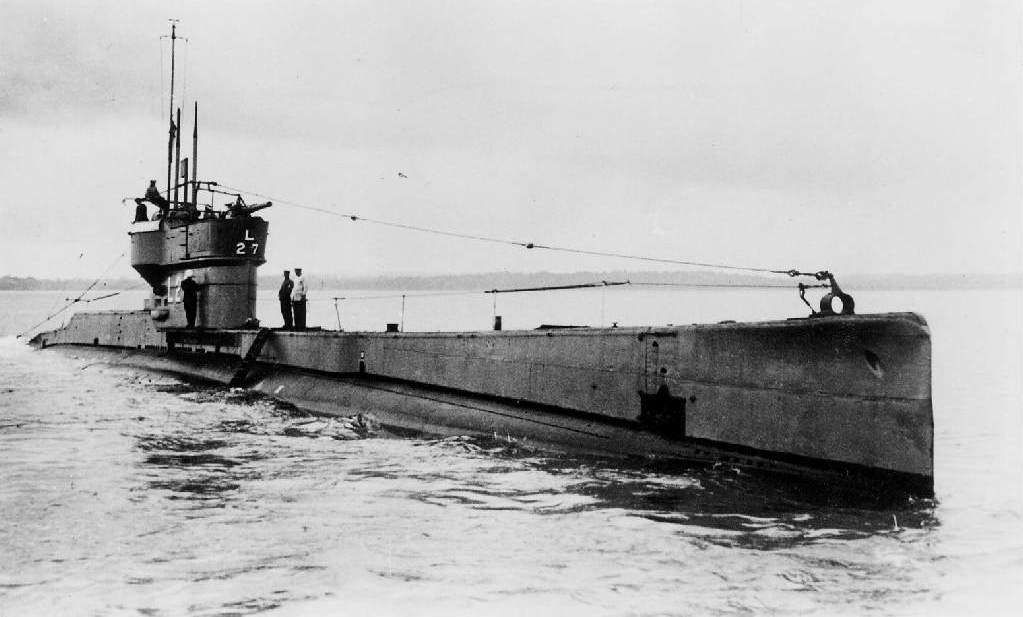

The Admiralty acted with an unwarranted degree of over-confidence. Beatty and Reginald Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force was dispatched to intercept Hipper, but without the close support of Jellicoe’s fleet. Thus Beatty sailed with the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron (the Lion, Tiger, Princess Royal), the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron (the older New Zealand and Indomitable), the dubious support of the pre-dreadnoughts of the 3rd Battle Squadron, the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron and the usual screening destroyers.

3 of 6

Beatty intended to rendezvous with the Harwich Force near Dogger Bank. Soon after, the light screens of both forces clashed and Hipper, astutely recognizing what was happening, bolted for home. Beatty and his battlecruisers began a grim stern chase, seeking to overtake and destroy their adversaries. Gradually the faster Lion, Tiger and Princess Royal began to get within range, until the Lion opened fire, at about 20,000 yards, concentrating initially on the rear ship, the hybrid battlecruiser Blücher, which was slightly lagging behind.

4 of 6

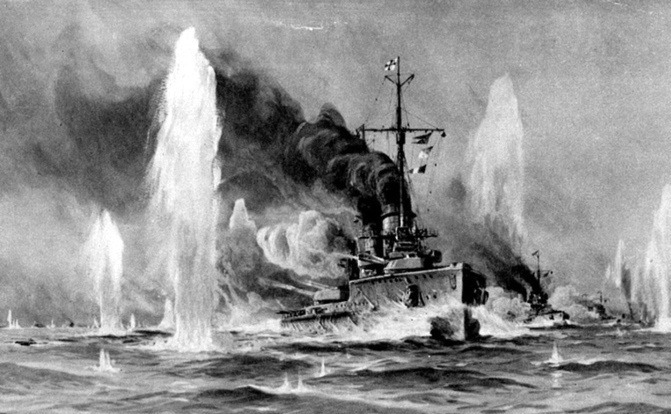

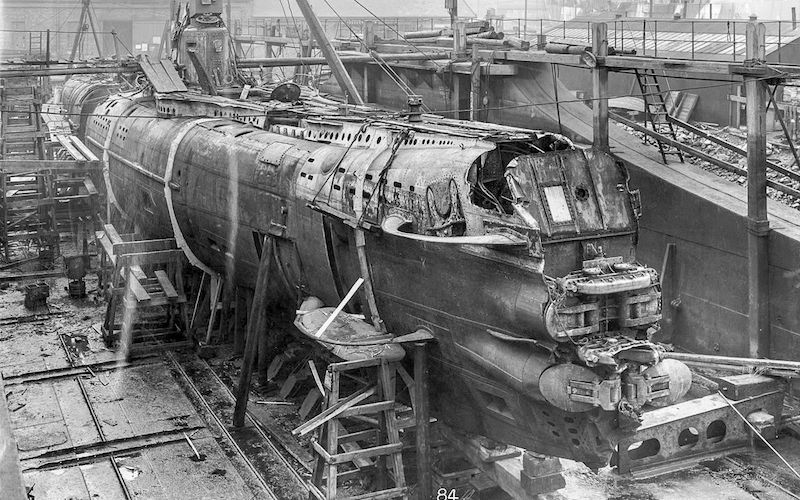

One shell from the Lion did crash down on her opposite number, the Seydlitz. It tore through the quarter deck and partially penetrated the barbette armour of the aft turret. The burst ignited the cordite charges in the working chamber and triggered a flash that spread in an instant into the magazine handling room and up into the turret above. As desperate men tried to escape they opened the door connecting with the adjoining superimposed turret, thereby inadvertently allowing the flames to rip through both to deadly effect. 159 men were killed in the conflagration.

5 of 6

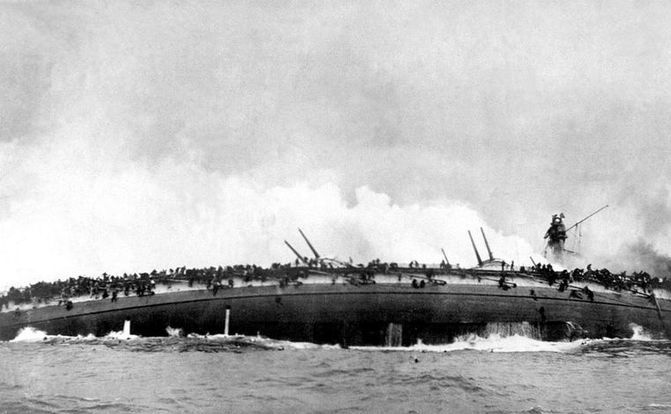

In response, German fire was concentrated on the Lion at the head of the British line, hitting her fifteen times and causing serious damage. Listing to port, she began to fall out of line. Despite this, Hipper and his ships were still in dire straits: the Blücher was by this time on fire and slowing down. But then fate intervened as Beatty sighted what he thought was a periscope and feared he had led his precious battlecruisers into a deadly submarine trap. He ordered an immediate turn to port, which allowed Hipper the precious breathing space to try to escape away to the southeast, abandoning the Blücher to her fate.

6 of 6

The crew of the Blücher fought to the end, but for the British the dramatic photos of her turning turtle as she sank were small compensation for the escape without further interference of the rest of the German battlecruisers.

The War at Sea: The first battles

During the Great War naval power was crucial even though there were no decisive battles. In the beginning the British retained essential control of their home waters and were able to avoid blockade and serious attack. Nevertheless, German warships bombarded English east coast towns, notably Hartlepool, Scarborough, and Whitby causing great popular outrage by doing so.

The War at Sea in 1916

During 1916 the German fleet sought again to implement its plan to attack the British in a major battle in an effort to weak the British Grand Fleet in a decisive manner. The plan led to the Battle of Jutland. The British did not fall for the German plan, however, despite having the larger fleet at Jutland, they failed to achieve the sweeping victory hoped by the Navy as well as the British public.

The War at Sea in 1917

During 1917 Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in an effort to stop the flow of supplies towards Britain. The attempt backfired when US President Woodrow Wilson declared war against Germany.

The War at Sea in 1918

By 1918 the Entente convoy system was very well established and German submarines were hunted down with great efficiency. On the surface few engagements to place, the most notably being the British raid at Zeebrugge. The war ended with the German fleet being disbanded after the sailors mutinied at Kiel.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Jeremy Black, Naval Warfare: A Global History since 1860, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland, 2017

- R.G. Grant, Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing, London, 2011