Persia and Afghanistan during the Great War

The Entente and Central Powers compete for Persia and Afghanistan

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, Britain had made it abundantly clear that it took very seriously any threat to India's northwest frontier. The defense of India was a military responsibility and could not rest solely on Britain's major bulwark, the Royal Navy. Since the Germans did not possess mastery of the seas, they were unable to threaten India from the coast. The chances of revolution from within the subcontinent diminished as British rule solidified. The Germans therefore focused their attention in 1914 towards Afghanistan, trying to provide incentives to the locals to invade India.

1 of 4

Responsibility for suggesting that the threat to India might be directed through the Khyber Pass belongs not with anybody in Germany but with Enver Pasha. In August 1914 the Ottoman minister of war spoke in extravagant terms to Hans Freiherr von Wangenheim about the Islamic fervor of Habibullah, the Emir of Afghanistan. He implied — falsely, the Germans subsequently concluded — that officers of the Turkish army were already in contact with the Emir and with Muslims in the subcontinent.

2 of 4

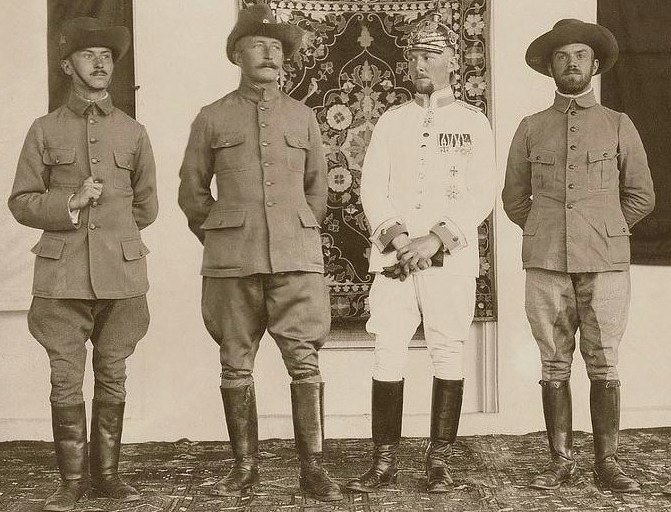

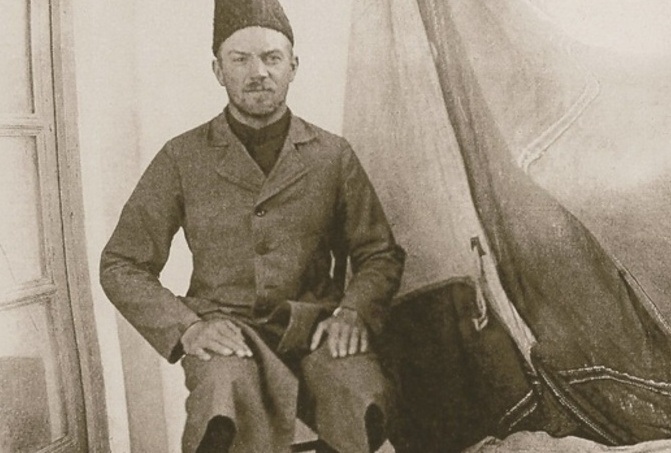

The German foreign office collected a group of fifteen people to form a German mission to Afghanistan. They arrived in Constantinople disguised as a travelling circus. Enver was not impressed: the decline in Turkish enthusiasm for the scheme can be charted from this moment. The only member of the party who was a Persian speaker was Wilhelm Wassmuss, who had been an interpreter and a fomentor of anti-British tribes in Bushire, southwest Iran.

3 of 4

A word to Emir Habibullah would be sufficient to unleash an Afghan invasion of India. The German foreign ministry was almost totally devoid of expertise in, and information on, Central Asia. But those whom they consulted endorsed Enver's encouraging scenario.

4 of 4

In December Wangenheim appointed Oskar von Niedermayer to the command, in Wassmuss's stead. But Niedermayer regarded himself as the leader of an independent military force, answerable to the general staff and not the foreign office; to Berlin and not to Constantinople.

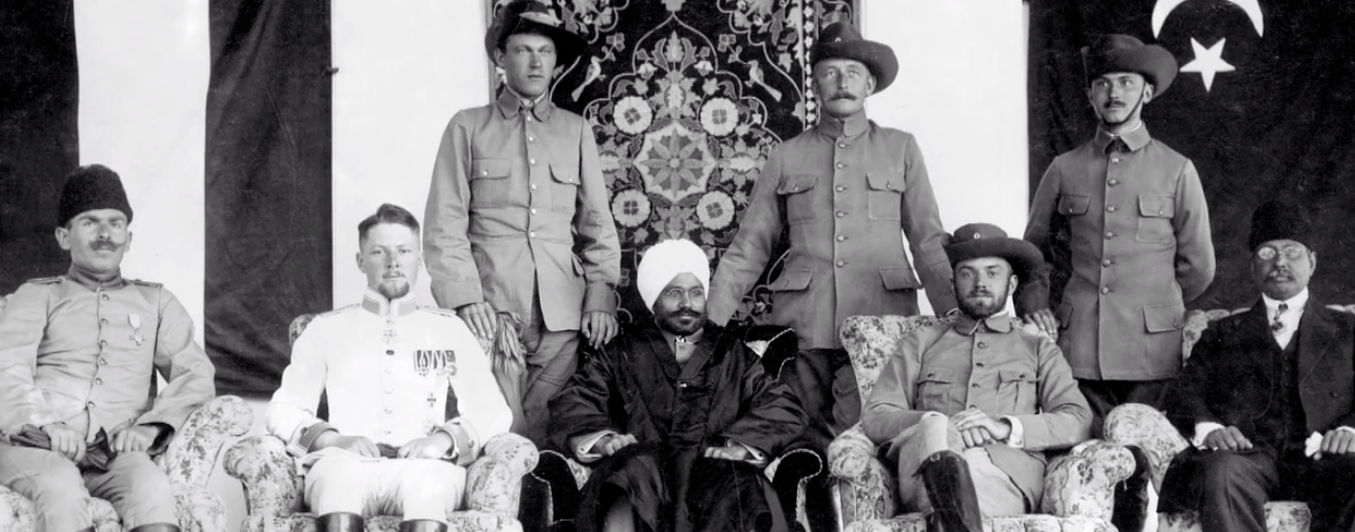

The conflict as to the ultimate responsibility, whether it was the army's or the foreign office's, and the friction between the leading personalities at the local level were exacerbated in April 1915 when Berlin decided on a second mission. Mohamed Barkatullah, an Indian revolutionary, presented himself at the German consulate in Geneva. Barkatullah claimed a friendship with Emir Habibullah's brother, Nasrullah. The Germans agreed to send a group of Indians, including Barkatullah and Kumar Mahendra Pratap, under the management of Werner Otto von Hentig to Kabul in order to foment rebellion across the frontier.

1 of 3

Pratap — considered by his German companion to be 'fanatical, moody and egocentric', and convinced that he himself was the real leader — took delight in stoking the Germans’ disputes. Ultimately, the issue became that of the subordination of the military to political control. But, even on ostensibly neutral territory, practicality gave the weight to the former, not the latter. Whatever the achievements of the mission to Afghanistan were, the credit is Niedermayer's.

2 of 3

Hentig was a diplomat who had served in Tehran. As the emissary of the Indian committee in Berlin, Hentig's party was clearly the foreign office's pigeon, not the general staff's. But in June 1915 Hentig and Niedermayer met in Tehran and agreed to proceed together. Nobody could decide who was the senior. The foreign office preferred to treat the two as independent. All those in the joint expedition took sides in the ensuing squabbles.

3 of 3

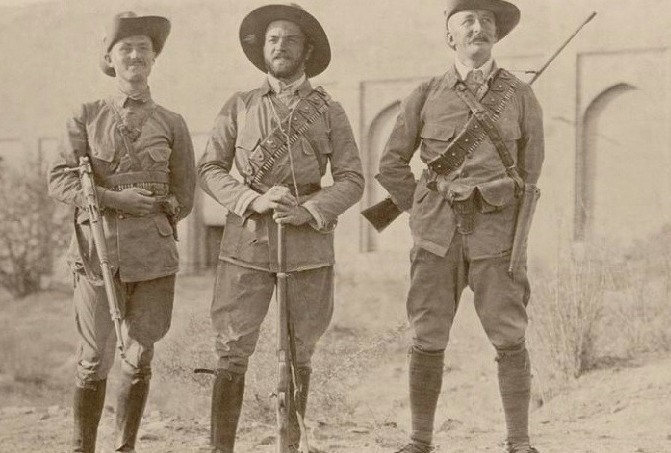

The German expedition to Afghanistan successfully evaded the Russians of the eastern cordon and crossed the frontier. Hentig wore a cuirassier's white tunic and helmet to enter Herat; the governor of the town was polite but unenthusiastic. Now the Germans found themselves virtual prisoners while the governor awaited instructions as to whether they could proceed. After the expedition reached the Afghan capital, here too their status was that of captive guests; they were not allowed into the city and their activities were circumscribed. Furthermore, the Emir was away at Paghman, his summer residence.

Caucasus Campaign

The complex political situation in the Caucasus escalated into a full fledged war when hostilities began between the Ottoman Empire and Russia.

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The campaign in Egypt started when the Turkish Army attacked the British positions at the Suez Canal. Turks surrendered at the Armistice of Mudros.

Mesopotamian Campaign

During the Great War British and Ottoman forces fought for control over Mesopotamia and its rich oil fields.

Gallipoli Campaign

During the Gallipoli Campaign the Entente organized a series of British-led amphibious landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula, with the intent of capturing Constantinople, the Ottoman empire's capital city.

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- Sean McMeekin, The Russian Origins of the First World War, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2011