Caucasus Campaign

Entente forces fight the Ottoman Empire for control of the Caucasus

2 November 1914 - 30 October 1918

The Caucasus Campaign was fought between the forces of Russia and the Ottoman Empire as part of the Middle-Eastern Front of the Great War. Later the conflict expanded, with Russia joined by Armenia, the British Empire and the Central Caspian Dictatorship - a short anti-Soviet administration proclaimed at Baku - and the Ottoman Empire aided by the German Empire, Azerbaijan and Georgia. In the end, although the Russians withdrew from the conflict after the Bolshevik Revolution, the Ottoman Empire was defeated.

1 of 3

Turkey's entry to the war did not merely add another member to the alliance of the Central Powers or another enemy to those the Entente were fighting already. It created a whole new theater of war, actual and potential, drawn in several dimensions: religious and insurrectionary as well as purely military.

2 of 3

The third front opened by Turkey's entry into the war, that in the Caucasus, was by far the most important, both for the scale of the fighting it precipitated and because of the consequences of the fighting. The Ottoman advance into the Russian Caucasus so alarmed the Tsarist high command that it prompted an appeal to Britain and France for diversionary assistance. This led to the campaign of Gallipoli, one of the Great War's most terrible battles but also its only epic.

3 of 3

Despite its initial failure in the Caucasus, which the Ottoman government took care to conceal at home, Turkey's influence on the war continued to ramify. For all its long decline, Turkey remained a menacing military presence in the memory of its neighbors, particularly its European neighbors.

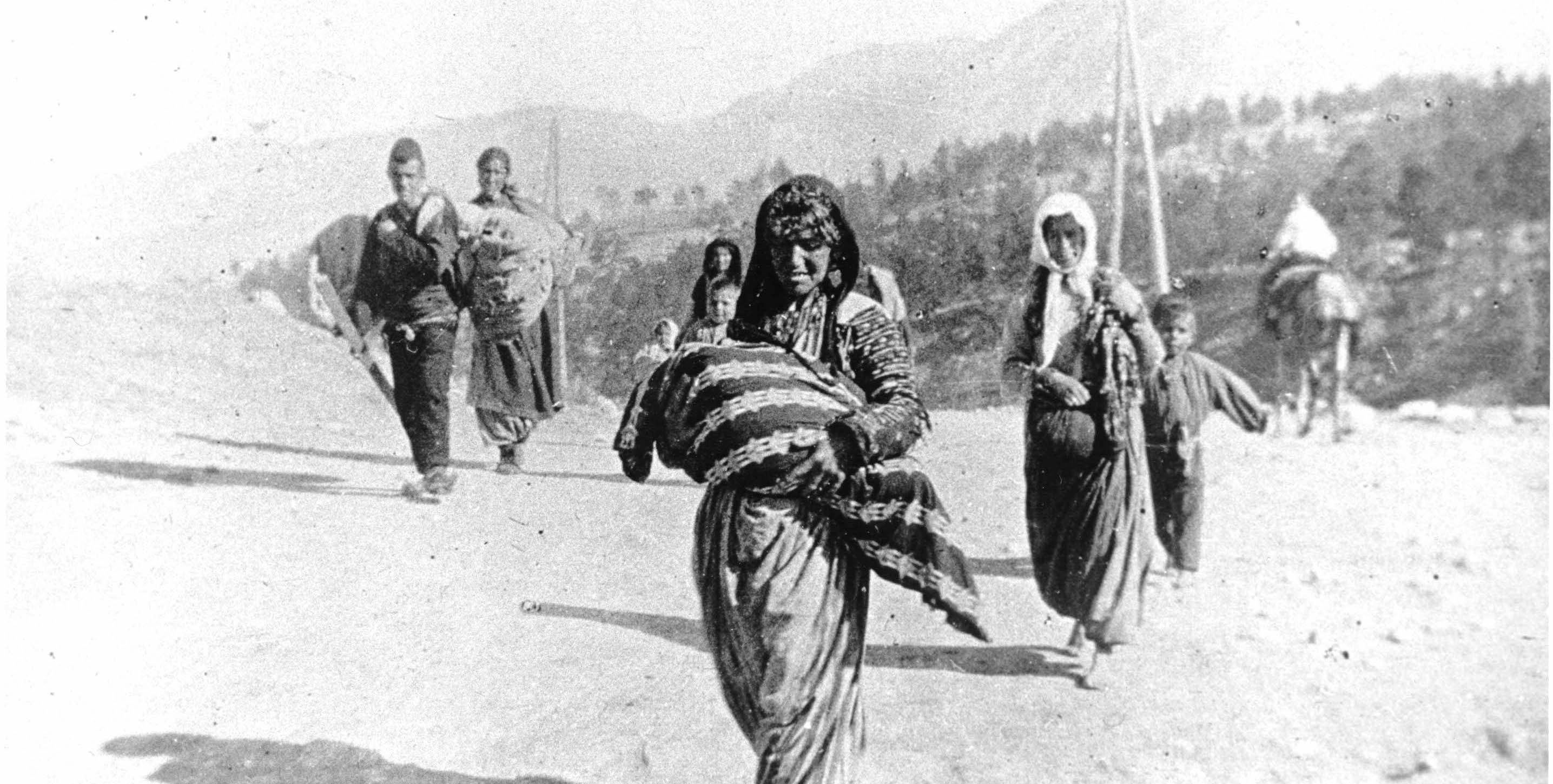

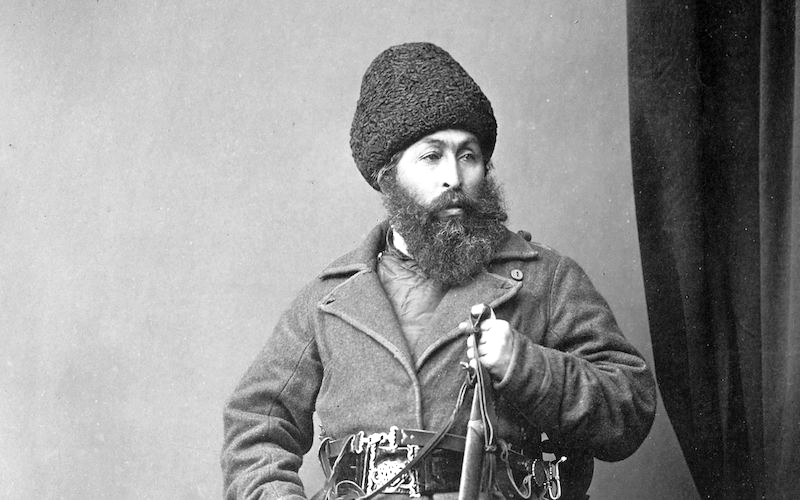

Russia's military concern for the Caucasus in 1914 was not its defense against Turkey but its internal security. Until 1864 Georgia had been Russia's principal frontier problem, with guerrilla warfare in the region shaping the soldiering experience of many. The extension of the Russian border in 1878 to a line south of the River Aras had increased the polyglot composition of the province's peoples. It also re-emphasized the colonial nature of Russian rule. Thus, the region was not ethnically Russian, but nor was it — if viewed as a whole — anybody else's. The region was economically desirable. Economic growth confirmed rather than submerged the ethnic tensions. Russia's solution to all this inherent volatility was Russification.

1 of 5

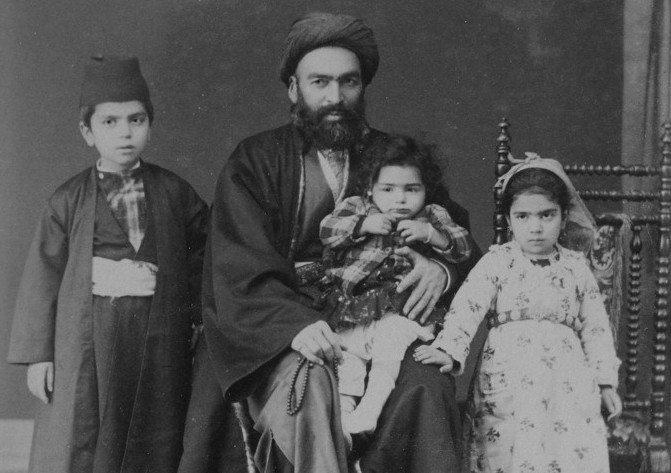

In 1897 only 34 percent of the population was Ukrainian or White Russian; the balance included three major groupings: Georgians (11.6 percent), Armenians (12 percent), and Tatars (16.3 percent). The Georgians were concentrated in the west and center, around Tiflis, and the Tatars to the east around Baku. The Armenians, as in Ottoman Turkey, had no obvious geographical focus, although they did constitute a narrow majority in Yerevan.

2 of 5

Copper, silver, zinc, iron, gold, cobalt, salt and borax were all to be found in the region. In addition to its natural resources, the Caucasus stood on the land route between Europe and Central Asia. Between 1908 and 1914, 70 percent of Persia's exports were routed through Russia.

3 of 5

Between 1878 and 1880, 75,000 Osman Turks were repatriated. Twelve thousand Russian peasant families were settled from elsewhere in the empire. Proportionately, the Muslim population declined. But nationalism, already strong among the Georgians, surfaced along with middle-class intellectualism among the Armenians and the Azerbaijanis. The 1905 revolution moderated Russian policy temporarily but sufficiently to increase the foothold of the local independence movements.

4 of 5

In 1907 the Dashnaktsutyun, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, formally adopted socialism. In 1912 a secret Azerbaijani organization, Musavat, was formed in Baku. Its public aim was to achieve political equality for all Muslims in Russia, while its private appeal rested on its call for the unification of all Muslim peoples. In the years preceding the war, Russia's policy in the region tightened once again. But nationalism, Islam and socialism, sometimes in conjunction, sometimes separately, threatened the stability necessary for sustained economic growth.

5 of 5

Russian diplomacy in the pre-war years aimed to neutralize and isolate eastern Anatolia, not overrun it. Its expansionism was directed towards Persia. By creating a cordon sanitaire between its own interests and Turkish irredentism, it freed itself for a forward policy in Azerbaijan. The southerly route adopted for the Baghdad railway was the most obvious manifestation of Russian success. In 1911 Germany recognized Russia's sphere of interest in northern Persia, and the two powers agreed that Russia would build the line from Tehran to Khanikin, south of Kirkuk, to link with the Berlin-Baghdad route.

Persia and Afghanistan during the Great War

Germany, with some Turkish assistance, tried to ally with Afghanistan in order for that country to instigate a potential revolt in India. In Persia the Germans tried to eject the British and Russian influences in order to gain access to its rich oil resources.

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The campaign in Egypt started when the Turkish Army attacked the British positions at the Suez Canal. Turks surrendered at the Armistice of Mudros.

Mesopotamian Campaign

During the Great War British and Ottoman forces fought for control over Mesopotamia and its rich oil fields.

Gallipoli Campaign

During the Gallipoli Campaign the Entente organized a series of British-led amphibious landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula, with the intent of capturing Constantinople, the Ottoman empire's capital city.

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003

- Charles king, The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus, Oxford University Press, New York, 2008