Operation Bagration

German Army Group Central is attacked and destroyed

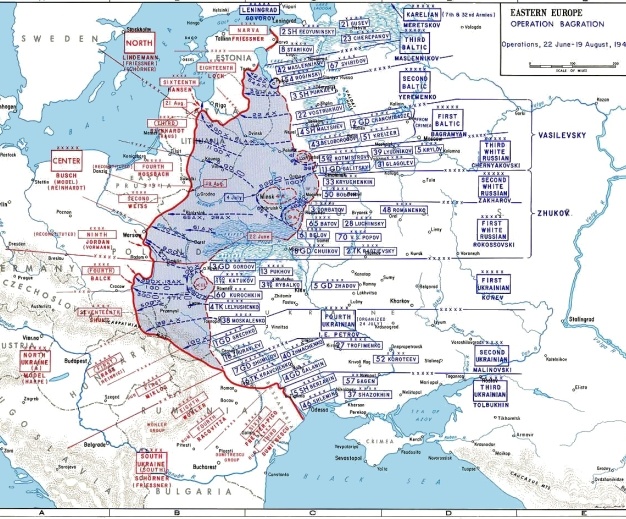

Operation Bagration was the codename for the Red Army Belorussian Strategic Offensive Operation during World War 2. This operation cleared the German troops from the Belorussian SSR and eastern Poland. The offensive was directed against the German Army Group Centre and resulted in the almost complete destruction of this Army Group. The Soviet armies involved were the 1st Baltic Front under Ivan Bagramyan, the 3rd Belorussian Front commanded by Ivan Chernyakhovsky, the 1st Belorussian Front commanded by Konstantin Rokossovsky, and the 2nd Belorussian Front commanded by G. F. Zakharov.

1 of 7

The operation was named after 18th–19th century Georgian Prince Pyotr Bagration. He was a general of the Imperial Russian Army who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Borodino during Napoleon’s invasion of Imperial Russia. It was here that the soldiers of Napoleon

I marched across the land-bridge between the Duna and Dniepr Rivers toward Moscow, the metropolis of the Czarist empire. During its retreat from Moscow the "Grand Army" perished while crossing the Beresina. Something similar was to take place 132 years later, only this time not in the depths of an icy winter, but during a hot summer.

2 of 7

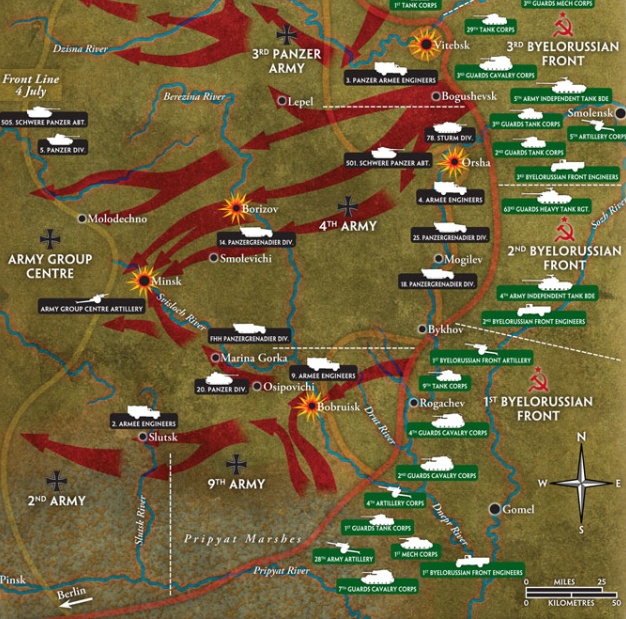

Belorussia had great, sometimes jungle like, forests interspersed with marshes, fields and villages, small lakes and streams, marshy lowlands, traversed by the northward-flowing Duna and the southward-flowing Dniepr with its many tributaries, among them the Beresina. Among the country's large cities were Vitebsk and Orsha, Mogilev, Bobruisk and, of course, Minsk, the capital city, from where the first Russian highway led through Smolensk to Moscow. In those summer days this entire country was to play an especially tragic role for hundreds of thousands of German soldiers.

3 of 7

The initial campaign against the Soviet Union had also passed through Belorussia. Great battles raged there during Operation Barbarossa until the noise of battle moved more and more toward the East. However, Army Group Center was unable to capture Moscow and the war returned, until following its retreat the army group was able to occupy a new, and this time, so it hoped, permanent front. Six defensive

battles were fought along the front in one year, but it held firm.

4 of 7

In this operation the Red Army showed that conducting Blitzkrieg was no German monopoly and that, in spite of the horrendous losses in the earlier fighting, it had both the means and the ability to drive successfully into a German front that had been held and fortified for many months.

5 of 7

Hitler’s strategy of ‘fortified localities’ had to be put into operation immediately at Mogilev, Bobruysk and elsewhere, with the predictable result that the Russians merely bypassed them and left them to be besieged by reserve troops. Although they were exhausted by constant combat over many months, under-equipped, outnumbered and largely unsupported from the air, Army Group Centre might have remained intact had it not been saddled with tactics as illogical and untutored as that of ‘fortified localities’ and other related concepts that Hitler invented.

6 of 7

Had the Führer visited the front more often, he might have seen for himself how Order No. 11, which called for ‘stubbornly defended strong points in the depth of the battlefield in the event of any breakthrough’, was a recipe for denuding the German line yet further, merely permitting further such breakthroughs.

7 of 7

The choice of the third anniversary of Barbarossa for the launch of Bagration was instructive: the destruction of Army Group Centre was in many ways the mirror image of what had happened in the early stages of Barbarossa, with strongpoints being encircled with bewildering speed by swarms of highly mobile opponents.

From Polotsk in the north, where it linked up with Army Group North, the front extended eastward in a great salient around Vitebsk, then between Orsha and Rogatchev in a large bridgehead east of the Dniepr, before running increasingly westward and then straight south from Pinsk to a point near Kovel, where it met Army Group North Ukraine. Thus Army Group Center - at that time the strongest German army group - under its Commander in Chief Feldmarschall Ernst Busch occupied an extended, semi-circular, eastward-facing salient approximately 1,100 kilometers in length and held by four armies.

1 of 6

The northern wing from Polotsk consisted of the Third Panzer Army with IX, LII and VI Army Corps (nine divisions), in the center the Fourth Army with XXVII, XXXIX and XII Corps (nine divisions) and finally the Ninth Army with XXXV, XXXXI and LV Corps (ten divisions).

2 of 6

The southern wing along the Pripyat Marshes was formed by the Second Army with three army corps. There were thus about 500,000 German soldiers (without Second Army), of wich about 400,000 in the actual front area, certainly an imposing number. This figure meant little, however, because most of the infantry divisions, which would have to bear the brunt of the fighting, were far below strength and had only five to seven battalions instead of the usual ten. The entire infantry combat strength of the Third Panzer Army, for example, was only 21,500 men, while the Ninth Army had only 24,000 trench fighters in the main line of resistance.

3 of 6

The entire army group had only six infantry and security divisions and a single panzer division4 in reserve, which it had moved into

positions behind the individual armies.The Luftwaffe was so tied down in the West and with the defence of the Reich that the commanding Luftflotte 6 had available only a very few flying units, including a mere 40 fighters. To compound the situation there was a shortage of fuel. The Luftwaffe was scarcely to appear during the coming heavy fighting.

4 of 6

The army group's commanders had another cause to worry. The entire rear zone in the area of forests and swamps between the Dniepr, Beresina and Pripyat Rivers was controlled by partisans as on no other front. Repeated large-scale antipartisan actions were carried out, but were unable to eliminate the nuisance of the partisan bands. Even in periods of relative quiet German forces could only travel the Mogilev-Beresina road in convoy, and movement by smaller units was quite impossible off this major road. The partisans mined roads, ambushed staff vehicles, killed motorcycle messengers, cut telephone lines, and so on.

5 of 6

The army group's overall situation was seen as only marginally stable and therefore the army group command proposed two plans to shorten the front, a move which would save forces and result in better defensive positions. One plan, the so-called "small solution," would have seen the Third Panzer Army abandon the salient around Vitebsk and the Fourth Army evacuate the bridgehead beyond the Dniepr. The "big solution" would have seen all three armies pulled back behind the Beresina.

6 of 6

Although the army group and the armies pushed for weeks for a withdrawal of the front to shorter lines, Hitler rejected any such move, even forbidding further work on positions in the rear and instead ordering the establishment of "fortified places," a concept "invented" by him. Vitebsk, Orsha, Mogilev and Bobruisk were so designated. The army group's Commander in Chief gave in and issued orders that the existing main line of resistance was to be defended no matter what.

The 1943 autumn soviet offensives

After the German failed attack at Kursk the Red Army staged a series of attacks across the Eastern Front. The Soviets manged to retake the cities of Kharkov, Orel, Kiev, Bryansk and Smolensk.

Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket

During the Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket the Russian Red Army tried to eradicate the encircled German forces. The Germans tried a breakthrough in order to escape encirclement, which resulted in heavy casualties. which

Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive

The Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive was a strategic offensive during World War Two which led to the lifting of the almost 900-day siege of Leningrad. After the bloodiest siege in human history, lasting almost 900 days, during which more than 1.1 million people died, Leningrad was finally liberated. Novgorod fell two days later as the Germans recoiled rapidly.

Battle of Ternopol

The battle of Ternopol, or battle of Kamianets-Podilskyi pocket was a battle in which the Red Army tried to surround and destroy the German 1st Panzer Army.

Crimean Offensive

The Crimean Offensive was a series of Red Army attacks directed against the German-held province of Crimea in southern Ukraine. German Army Group A was composed of German and Romanian soldiers. The offensive ended when the Axis forces evacuated Crimea at the city of Sevastopol. The Germans and Romanians suffered heavy casualties during the evacuation.

Battle of Brody

The Battle of Brody took place during the Soviet Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive. This offensive saw the formation of a pocket at Brody were a large number of German forces were surrounded and destroyed. The Lvov-Sandomierz offensive was launched so that the Germans would be dislodged out of Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The Red Army accomplished all of its objectives by the end of this offensive.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Alex Buchner, The German defensive battles on the Russian front 1944, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 1995