Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive

Red Army liberates the besieged city of Leningrad

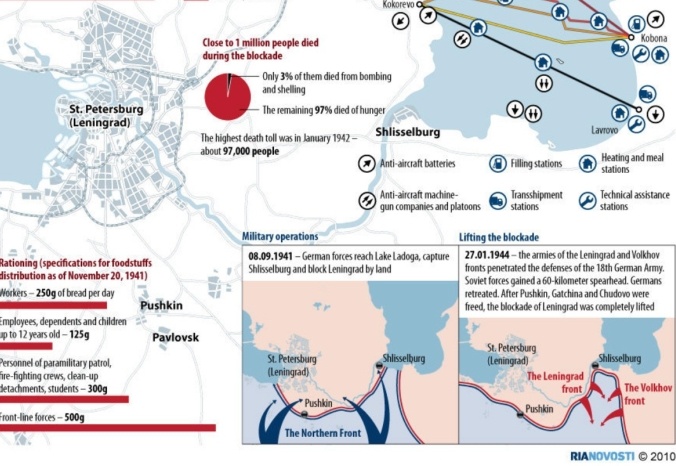

The Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive was a strategic offensive during World War II. It was launched by the Red Army’s Volkhov, Leningrad and 2nd Baltic Fronts against the Wehrmacht’s Army Group North. The offensive led to the lifting of the almost 900-day siege of Leningrad. After the siege, the offensive ended with the Leningrad Front’s push across the Narva river, which the Germans managed to stop.

1 of 7

General L. A. Govorov’s Leningrad Front and General Kirill A. Meretzkov’s Volkhov Front took advantage of the freezing weather to cross the Gulf of Finland with its iced-up lakes and swamps and attack the German 18th Army on both flanks.

2 of 7

In 47 days of fighting, the Leningrad and Volkhov fronts advanced 300 km and shattered the previously impregnable defences of Army Group North. The siege of Leningrad, after 880 days, was over. However, the agony of Leningrad's defenders was not. At the end of the war, Stalin proclaimed Leningrad as one of five 'Hero Cities' and promised to rebuild the city promptly. In fact, reconstruction efforts lagged for years.

3 of 7

After the bloodiest siege in human history, lasting almost 900 days, during which 150,000 shells and 100,000 bombs fell on the city and more than 1.1 million people died, Leningrad was finally liberated. Novgorod fell two days later as the Germans recoiled rapidly

4 of 7

Stalin was embarrassed by the true scale of Soviet casualties at Leningrad and ordered blanket silence concerning details about the siege. Rather than honoring Soviet suffering and heroism on the Leningrad front, Stalin sought to conceal it. Furthermore, Stalin was suspicious of Zhdanov and his Leningrad clique and conducted his final purge in 1950. This purge resulted in the arrest and execution of many of those who had organized the defence of the city during Operation Barbarossa.

5 of 7

Hitler had intended to demolish Leningrad as both a symbol and a center of Soviet power, but he accomplished neither. Thus in strategic terms, the German effort against Leningrad was a failure. Yet in operational terms, the German siege of Leningrad effectively isolated three Soviet armies for over two years. It also forced six other armies to conduct repeated costly frontal assaults to try and end the siege. At the start of the final offensive, the Red Army had to mass the equivalent of over 60 divisions in the Leningrad-Volkhov area in order to dislodge 20 German divisions. And the Soviets still failed to encircle and destroy a single one of the German divisions.

6 of 7

Soviet leaders learned quickly at Leningrad, and their effectiveness increased over the course of the siege. Yet even during the successful offensive, the Soviets still suffered a 40% casualty rate and lost 7.5 men for every German killed or captured. Indeed, the Soviet ability to rapidly regenerate combat power was critical to their eventual success, particularly in the rapid rebuilding of the 2nd Shock Army. Once Generals Meretskov and Govorov learned from their earlier failures and were given the time and resources to prepare powerful set-piece offensives, the days of the siege were numbered.

7 of 7

In less than three weeks of fighting, the Soviet forces had driven the Germans 100 km south and southwest of Leningrad and 80 km west of Novgorod. Plus the Germans had been cleared from the main railroad line between Leningrad and Moscow. Leningrad had suffered enormously from the blockade and during its battle of defense. More than one thousand factory buildings and almost ten thousand apartment buildings were destroyed or severely damaged due to enemy shelling and aerial bombardments.

When General Georg von Kuchler withdrew Army Group North from its forward positions, Hitler replaced him with Walter Model. Model managed to persuade the Führer that a ‘Schild und Schwert’ (shield and sword) strategy should allow minor withdrawals as part of a larger, planned counter-offensive. The Germans constructed a series of fortifications in the region called the Panther line. In the meantime, the Red Army had reached a line from Narva to Pskov to Polotsk.

1 of 7

Model was able to persuade Hitler of certain things, such as the withdrawal, that other generals could not, because the Führer admired him and was utterly convinced of his loyalty. He argued with Hitler to his face, but only on matters of military policy. Model would not allow any criticism of Hitler at his HQ. Because he led from the front, constantly being seen in the front line, Model was popular with the troops in the way that a number of other German château-generals were not.

2 of 7

Hitler set a problem for OKH planners which threw light on the severe manpower problems that Germany was facing by then. Between the outbreak of war and late 1943, the standard German infantry division consisted of three regiments totalling nine rifle battalions. Each regiment had twelve rifle and heavy-weapons companies and a howitzer and anti-tank company, and the division itself also had a separate anti-tank and reconnaissance battalion, which brought the average division size up to 17,000 men.

3 of 7

Before the Soviet offensive, divisions were reorganized to comprise three regiments of only two battalions each, bringing the average size down to 13,656 men. Three months later, Hitler was forced to ask how divisions could be cut back to 11,000 men each, without affecting firepower and overall combat strength. The planners considered that this was impossible, and put forward a compromise solution of divisions of 12,769 in size. With Germany simply running out of soldiers by January 1944, while divisions still had to hold their sections of many miles of crumbling fronts, such demoralizing reorganizations were a potent foretaste of her coming disaster.

4 of 7

Unlike the rest of the Wehrmacht fighting on the Eastern Front, the Army Group North had succeeding in fighting previous Soviet

offensives to a standstill. However, Army Group’s North defensive prowess led to the OKH transferring several of its veteran infantry divisions to other more threatened sectors and replacing them with low-quality Luftwaffe field divisions. With most of its armor, air support and veteran infantry gone, the Army Group was gradually transformed into a static defence formation. In the meantime Soviet capabilities in the region were expanding with a new infusion of reinforcements.

5 of 7

General Georg Lindemann's 18th Army had 20 divisions in six corps. It defended a front stretching from the Oranienbaum bridgehead, to the south side of Leningrad and then southwards to Novgorod. Although Lindemann had developed deep defences, it was a very wide front for his troops to hold. SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner's 3rd SS-Panzerkorps, consisting of the 9th and 10th Luftwaffe Field Divisions on the right and the 11th SS Panzergrenadier Division ‘Nordland’ and the 4th SS Panzergrenadier Brigade ‘Nederland’ on the left, took over the Oranienbaum sector.

6 of 7

The ‘Nordland’ Division was a relatively strong formation, but its Panzer battalion was not yet operational since the Panther tanks it had been issued were defective. Instead, the division had a battalion with 25 StuG III assault guns while the ‘Nederland’ Division had seven more.

7 of 7

The two weak Luftwaffe field divisions were reinforced with two infantry battalions from the reliable 170th Infanterie-Division, two assault gun batteries, two Panzerjager batteries and plenty of flak guns. The OKH also sent Panther Detachment ‘Maeckert’ to provide additional anti-tank defences around Oranienbaum. These Panthers had defective engines and were only semi-mobile. Steiner used these additional forces to conduct several spoiling attacks, but they were too weak to disrupt the upcoming Soviet offensive.

The 1943 autumn soviet offensives

After the German failed attack at Kursk the Red Army staged a series of attacks across the Eastern Front. The Soviets manged to retake the cities of Kharkov, Orel, Kiev, Bryansk and Smolensk.

Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket

During the Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket the Russian Red Army tried to eradicate the encircled German forces. The Germans tried a breakthrough in order to escape encirclement, which resulted in heavy casualties. which

Battle of Ternopol

The battle of Ternopol, or battle of Kamianets-Podilskyi pocket was a battle in which the Red Army tried to surround and destroy the German 1st Panzer Army.

Crimean Offensive

The Crimean Offensive was a series of Red Army attacks directed against the German-held province of Crimea in southern Ukraine. German Army Group A was composed of German and Romanian soldiers. The offensive ended when the Axis forces evacuated Crimea at the city of Sevastopol. The Germans and Romanians suffered heavy casualties during the evacuation.

Operation Bagration

Operation Bagration was the codename for the Red Army Belorussian Strategic Offensive Operation during World War 2. This operation cleared the German troops from the Belorussian SSR and eastern Poland. The offensive was directed against the German Army Group Centre and resulted in the almost complete destruction of this Army Group.

Battle of Brody

The Battle of Brody took place during the Soviet Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive. This offensive saw the formation of a pocket at Brody were a large number of German forces were surrounded and destroyed. The Lvov-Sandomierz offensive was launched so that the Germans would be dislodged out of Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The Red Army accomplished all of its objectives by the end of this offensive.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Alex Buchner, The German defensive battles on the Russian front 1944, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 1995

- Robert Forczyk, Peter Dennis, Leningrad 1941-44, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2009

- Albert Pleysier, Frozen Tears The Blockade and Battle of Leningrad, University Press of America, Lanham, Maryland, 2008

- Harrison Salisbury, The 900 Days The Siege Of Leningrad, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2003

- Rebecca Mace