The 1943 autumn soviet offensives

Russian forces attack German positions in Russia and Ukraine

24 August - 22 Decembrie 1943

After the Wehrmacht’s withdrawal with unacceptable losses at the battle of Kursk the scene was set for a series of enormous Soviet offensives across the eastern part of the Eurasian land mass that were only to end with Germany’s surrender in Berlin. In its summer offensive after the successful defence of Kursk, the Red Army recaptured Orel, Kharkov, Taganrog and Smolensk, forcing the Germans back to the Dnieper river and cutting off the Seventeenth Army in the Crimean peninsula. Afterwards, during the autumn the Soviets retook the Donetsk basin and eventually Ukraine’s capital, Kiev.

1 of 7

For all the advances made against the Germans in the west between D-Day and the crossing of the Rhine it was on the Eastern Front that the war against Germany was won. Between Operation Barbarossa and December 1944, the Germans lost 2.4 million men killed there, against 202,000 fighting the Western allies. The cost of inflicting such casualties was uneven: between D-Day and VE Day (Victory in Europe Day), the Russians suffered more than 2 million casualties, three times that of the British, Americans, Canadians and French fighting forces put together.

2 of 7

For the German soldiers on the ground, in their long, bitter withdrawal from their highwater mark at Kursk, survival took on greater meaning than any lingering hopes of victory. For the Russians, liberating their cities and towns involved discovering the horrors of the

German occupation. At Orel, which was a typical example, half the buildings and all the bridges had been destroyed. There were only 30,000 survivors from a pre-war population of 114,000. The rest of them were sent to Germany as slave labour or shot, or died of disease or starvation.

3 of 7

The Red Army hardened its already rock-like heart still further against the enemy, encouraging it to see them as subhuman, and

instilling a determination to punish all Germans – civilians as well as military – now that the jackboot was on the other foot. The innocence or otherwise of individual Germans was immaterial, because it was not so much they who were being punished as their husbands, fathers and sons. Human pity was now beside the point.

4 of 7

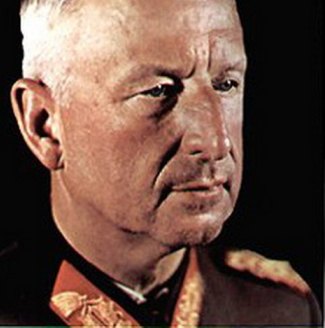

It was to take a further eighteen months of unimaginable horror and slaughter before the war finally came to an end. The blame for this can largely be put down to the efficiency, determination and obedience of the Wehrmacht. Had Hitler passed over ultimate decision-making to a committee of its best brains, and appointed Erich von Manstein as supreme commander of the Eastern Front, all that it would have meant at that stage was that the defeat would have taken longer and cost many more German and Russian lives.

5 of 7

British historian Alan Clark has pointed out that from December 1943 the Führer had been aiming at breaking the Allied coalition through emphasizing “the apparent impossibility of its task and the incompatibility of its members”. Seen in this context his defence of every inch of territory in the east was explicable. Stalin had been making speeches about Hitler’s aim of using fear of Communism as a way of splitting the Grand Coalition against Germany. The Soviet Information Bureau (Sovinform) had been issuing statements lauding Russia’s alliance with the Western Allies. There is plenty of evidence for how this was reciprocated in Britain and America.

6 of 7

If Hitler had had a better understanding of the true nature of the alliance against him, he would have realized that its desire to extirpate him and his New Order would always be greater than any mutual suspicions and antipathies within it. To believe anything else was mere desperation, for as he had written in Mein Kampf: “Any alliance whose purpose is not the intention to wage war is senseless and useless.”

7 of 7

Heavy fighting on the Eastern Front prevented the Germans from devoting much of their resources to the struggle with Britain and the United States. The need for Germany to leave large forces in the west and south, and to defend her home industries against Allied air attack, relieved the pressure the Third Reich could bring to bear on the Soviet Union.

Hitler came under pressure from Field Marshal Erich von Manstein and the Romanian dictator Marshal Ion Antonescu to evacuate the German and Romanian forces from the Crimea, which could have been used in the defence of Romania and Bulgaria. Hitler’s obstinate refusal to do so meant the fall of both countries in short order, and the eventual destruction of the army group there. Hitler had a scheme for the Crimea to become a solely Aryan colony from which all foreigners would be permanently banned. He hung on to his dream for it long after military considerations dictated that they needed to be – at the very least – postponed.

1 of 7

Colonel Nicolaus von Below wrote of this period: “Hitler foresaw threatening developments on the Eastern Front earlier and with greater clarity than his military advisers, but he was determined with great obstinacy not to accede to the request of his army commanders to pull back fronts, or would do so exceptionally only at the last minute. The Crimea was to be held at whatever cost, and he refused to entertain Manstein’s arguments in the matter.” A quarter of a million troops were therefore lost to the German line. It did not affect the outcome of the war.

2 of 7

Given enough warning, the Wehrmacht was in fact excellent at strategic withdrawals. It made thorough preparations improving roads, bridges and river crossings. It camouflaged assembly areas and made precise calculations about what equipment could be moved and the amount of transport necessary, and about what needed to be destroyed. Then command posts, headquarters, medical and veterinary posts were established to the rear before the withdrawal began. The problems were of course multiplied once the Wehrmacht was forced back on to German soil, because millions of panicky refugees wanted to escape the Red Army too.

3 of 7

The decision not to evacuate Crimea, according to its own lights was a strategic error. Like the decision to leave German troops on the Kerch peninsula in order to try to recapture the Caucasus one day, it was actuated by Hitler’s hope for a new assault on the southern USSR, long after such an attack was rationally possible.

4 of 7

“A series of withdrawals by adequately large steps would have worn down the Russian strength, besides creating opportunities for counter-strokes,” General Kurt von Tippelskirch stated of this immediate post-Kursk period. “The root cause of German defeat was the way her forces were wasted in fruitless efforts, and above all, fruitless resistance at the wrong time and place.” Manstein did his best with a mobile defence across southern Russia that seems to have been too subtle for Hitler. The Fuhrer constantly issued “Stand or die” orders freezing the defensive lines, such as at Kharkov after the Soviets broke through on.

5 of 7

It took no fewer than seven conversations for Manstein to get Hitler’s permission to retreat to the line of the Dnieper. Falling back there, Manstein ignored Hitler and allowed Kharkov to fall. This was felt further down the line of command: General Friedrich von Mellenthin, Chief of Staff of the 48th Panzer Division which was retreating to the Dnieper, complained bitterly of the way that “During the Second World War the German Supreme Command could never decide on a withdrawal when the going was good. It either made up its mind too late, or when a retreat had been forced upon our armies and was already in full swing.”

6 of 7

The Wehrmacht was also expert in the policy of scorched earth, of which Army Group South’s retreat to the Dnieper was the exemplar, For this operation Manstein received an eighteen-year jail sentence in 1949. He served only four years. “The wide spaces of Russia favour well-organized withdrawals,” recalled Mellenthin. “Indeed if the troops are properly disciplined and trained, a strategic withdrawal is an excellent means of catching the enemy off balance and regaining the initiative.” Yet, for all its expertise, Hitler gave the Wehrmacht as little time as possible to organize such retreats, on those rare occasions when he authorized them at all.

7 of 7

Almost throughout this period the Germans inflicted higher casualties on the Russians than they received, but crucially never more than the Soviets could absorb. Attacks were undertaken by the Red Army without regard to the cost in lives, an approach which German generals could not adopt because of a lack of adequate reserves.

Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket

During the Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket the Russian Red Army tried to eradicate the encircled German forces. The Germans tried a breakthrough in order to escape encirclement, which resulted in heavy casualties. which

Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive

The Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive was a strategic offensive during World War Two which led to the lifting of the almost 900-day siege of Leningrad. After the bloodiest siege in human history, lasting almost 900 days, during which more than 1.1 million people died, Leningrad was finally liberated. Novgorod fell two days later as the Germans recoiled rapidly.

Battle of Ternopol

The battle of Ternopol, or battle of Kamianets-Podilskyi pocket was a battle in which the Red Army tried to surround and destroy the German 1st Panzer Army.

Crimean Offensive

The Crimean Offensive was a series of Red Army attacks directed against the German-held province of Crimea in southern Ukraine. German Army Group A was composed of German and Romanian soldiers. The offensive ended when the Axis forces evacuated Crimea at the city of Sevastopol. The Germans and Romanians suffered heavy casualties during the evacuation.

Operation Bagration

Operation Bagration was the codename for the Red Army Belorussian Strategic Offensive Operation during World War 2. This operation cleared the German troops from the Belorussian SSR and eastern Poland. The offensive was directed against the German Army Group Centre and resulted in the almost complete destruction of this Army Group.

Battle of Brody

The Battle of Brody took place during the Soviet Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive. This offensive saw the formation of a pocket at Brody were a large number of German forces were surrounded and destroyed. The Lvov-Sandomierz offensive was launched so that the Germans would be dislodged out of Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The Red Army accomplished all of its objectives by the end of this offensive.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000