Battle of the Korsun–Cherkassy Pocket

German Army Group South is surrounded by Soviet forces

January 24, 1944 - February 16, 1944

The launch of the Soviet Korsun–Shevchenkovskiy offensive led to the battle of the Korsun-Cherkassy pocket. In this battle the 1st and 2nd Ukrainian Front, led by Nikolai Vatutin and Ivan Konev, encircled the German Army Group South in a pocket close to the Dnieper river. The victory of the Soviet Red Army in this battle marked a significant change in the strength and numbers of the german forces.

1 of 7

During their winter offensive, the Soviets had succeeded in bringing about the collapse of the German defenses on the middle Dniepr, crossed the river and advanced westward. The only German force still holding a front along the river was the Eighth Army, with the 11th and 42nd Army Corps, which held a sector approximately 100 kilometers long between Kanev and Cherkassy. This sector extended much further to the east than the remainder of the German front. The German units there had held their positions throughout January.

2 of 7

Feldmarschall von Manstein, Commander-in-Chief of Army Group South, had been unable to move Hitler to give up this bulge in the front. They must fight for time until the situation was clarified by the expected invasion in the West, and therefore must hold out where they were, was Hitler's argument. He therefore refused to order a withdrawal of the front - until it was too late.

3 of 7

Manstein was attacked on the Dnieper by the 1st Ukrainian Front under Zhukov and the 2nd Ukrainian Front under Konev, perhaps the best two Russian generals since Vatutin had been assassinated by Ukrainian nationalist partisans. A fierce struggle developed, but scarcely heard of in the West. It lasted three weeks, during which two German army corps were cut off in a salient and were extricated by Manstein only at the cost of 100,000 casualties.

4 of 7

The economic importance of the Ukraine, both in terms of mineral and industrial resources and as a rich agricultural region, made Hitler especially reluctant to agree to withdrawals urged on him by the commanders on the spot. They were often supported by the Chief of the Army General Staff. In rejecting such advice, or following it slowly, Hitler not only acted out of regard for the economic importance of the area but also the fact that shortening the lines freed Russian as well as German units, often meant that heavy equipment and supply dumps could not be evacuated, and was likely to add to the strength of the Red Army.

5 of 7

Although they would not admit it openly many of Germany's military leaders were becoming convinced that they were losing the war and would be defeated. They preferred that the defeat come about in the least messy way possible. Hitler, on the other hand, still wanted and hoped to win, if not the whole war, at least a major part of it. Thus he saw the need for Germany to hold as much of the occupied territories as possible as a basis for victory or at least an advantageous or partial peace.

6 of 7

When given unpleasant advice by those military advisors he trusted, like Admiral Dönitz or General Model, Hitler was quite prepared to accept it. He sensed—correctly it should be noted—their devotion not only to him personally but to his vision of ultimate German victory. If he distrusted the advice of others, it was because he sensed a difference not only on tactics but in basic orientation. In the meantime he retained some of them, relieved others, occasionally followed their advice, and continued his program of massively bribing them all regularly in the hope that this would assure their loyalty.

7 of 7

Arguments over appropriate tactics for the Germans in the face of Soviet offensives marked the winter of 1943-44. From the Soviet side, the aim was obvious: a series of hammer blows was designed to force the Germans -together with what satellite troops still fought alongside them- out of the bulk of the Soviet territory they still occupied in the north and south. Most of the economically valuable land still held was in the south and it was here that the Red Army concentrated the bulk of its offensive forces.

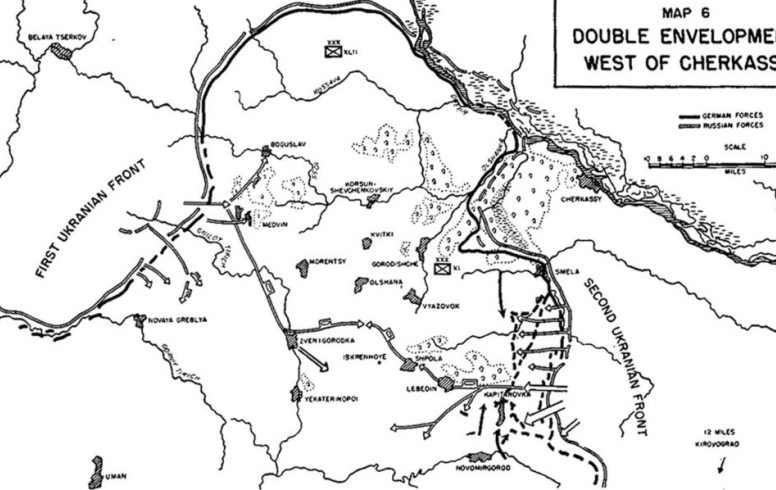

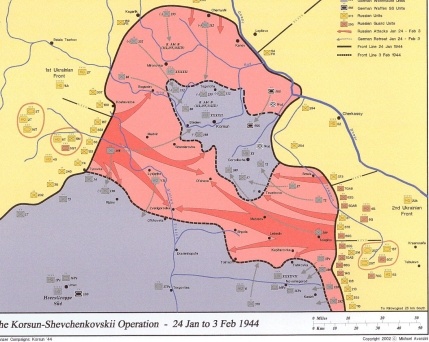

The Soviets launched an offensive thrust in the direction of Uman and Vinnitsa with the First Ukrainian Front. This was halted and thrown back after heavy fighting. Uman, the supply base for Army Group South, was saved. Following this setback the Soviets turned to the bulge in the German front near Cherkassy. A major offensive followed. The Fifth Guards Tank Army of the Second Ukrainian Front attacked from the east against the German 11th Corps. Following a violent artillery bombardment, Army General Vatutin's First Ukrainian Front resumed its breakthrough attempt. In the east the Soviets succeeded in breaking through Eighth Army's front.

1 of 7

Operations at the end of December suggest the extent of German self-deception. Manstein launched a major counterattack along the Korosten-Kiev Line and destroyed what turned out to be Soviet deception forces covering for another major offensive by Vatutin’s First Ukrainian Front. On Christmas day, the real Soviet offensive began. The First Guards and First Tank Armies, led by 14 infantry divisions and 4 mechanized corps blasted through German defenses and headed southwest toward Berditchev and Kazatin. This move threatened Army Group South’s entire left flank.

2 of 7

Sustained fighting over the past six months had decimated the German divisions. In early January, the 13th Corps reported that its divisions were down to less than 300 infantrymen, and the whole corps had a frontline strength equivalent to that of a single regiment. So desperate was the manpower situation that reinforcing divisions from the west often were committed to the fight without time to acclimatize to theater conditions and in some cases before all their equipment and weapons had arrived.

3 of 7

Manstein desperately requested permission to pull back the remaining troops along the Dnepr to free up reserves. The OKH at Hitler’s direction did allow some pullbacks and promised reinforcements, but it failed to give Manstein the kind of operational freedom the

grave situation demanded. After Christmas the lead spearheads of First Ukrainian Front reached Kazatin, a major supply center, and destroyed hundreds of German trucks. By evening the Germans held only half the city, while the Fourth Panzer Army appeared on the brink of collapse.

4 of 7

The spearheads of the First and Second Ukrainian Fronts met northeast of Uman near Svenigorodka. The German salient containing the 11th and 42nd Army Corps had been cut off from all contact with the rear. Despite all countermeasures, two German corps had been encircled in five days. Something had to happen, and quickly, if a second Stalingrad was to be avoided. The most rational solution would have been to give the order to both corps for an immediate breakout to the southwest to reestablish contact with the German front and help close the enormous gap which had arisen between First Panzer Army and Eighth Army.

5 of 7

In early January, Vatutin’s First Ukrainian Front worked its way around the Germans’ right flank and suddenly positioned itself to threaten the security of Army Group South. Manstein visited Hitler and requested permission to abandon the Dnepr bend. However, knowing Hitler’s predispositions, he was unwilling to suggest that his army group pull all the way back to the Bug River. Besides the threat to the German forces remaining near the Dnepr, the gap between Army Group Center and Army Group South had grown to over 160 km. Only the existence of the Pripyat Marsh prevented the Soviets from destroying the entire German position on the front.

6 of 7

Initially, all that the Germans could do was to insert two infantry divisions into the gap in an effort to provide at least a makeshift defence there. However, the most senior level of the German command not only forbade a breakout from the pocket which was forming, but proposed that the Russian forces which had broken through be encircled.

7 of 7

Hitler was still planning large-scale operations. An offensive was to be carried out, which incorporated the territory still held by the two corps around Kanev-Korsun. In his opinion the Soviet divisions had been exhausted and bled to death during the heavy fighting of the past winter. A powerful German thrust was to be carried out along the Dniepr to Kiev, cutting off everything Russian that had advanced across the river to the West. The plan would have been good if it had corresponded to reality and to the facts. But these looked quite different at the front than in Führer Headquarters 1,000 kilometers away.

The 1943 autumn soviet offensives

After the German failed attack at Kursk the Red Army staged a series of attacks across the Eastern Front. The Soviets manged to retake the cities of Kharkov, Orel, Kiev, Bryansk and Smolensk.

Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive

The Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive was a strategic offensive during World War Two which led to the lifting of the almost 900-day siege of Leningrad. After the bloodiest siege in human history, lasting almost 900 days, during which more than 1.1 million people died, Leningrad was finally liberated. Novgorod fell two days later as the Germans recoiled rapidly.

Battle of Ternopol

The battle of Ternopol, or battle of Kamianets-Podilskyi pocket was a battle in which the Red Army tried to surround and destroy the German 1st Panzer Army.

Crimean Offensive

The Crimean Offensive was a series of Red Army attacks directed against the German-held province of Crimea in southern Ukraine. German Army Group A was composed of German and Romanian soldiers. The offensive ended when the Axis forces evacuated Crimea at the city of Sevastopol. The Germans and Romanians suffered heavy casualties during the evacuation.

Operation Bagration

Operation Bagration was the codename for the Red Army Belorussian Strategic Offensive Operation during World War 2. This operation cleared the German troops from the Belorussian SSR and eastern Poland. The offensive was directed against the German Army Group Centre and resulted in the almost complete destruction of this Army Group.

Battle of Brody

The Battle of Brody took place during the Soviet Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive. This offensive saw the formation of a pocket at Brody were a large number of German forces were surrounded and destroyed. The Lvov-Sandomierz offensive was launched so that the Germans would be dislodged out of Ukraine and Eastern Poland. The Red Army accomplished all of its objectives by the end of this offensive.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Alex Buchner, The German defensive battles on the Russian front 1944, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, Pennsylvania, 1995