New Guinea Campaign

Allied forces defeat Japan on New Guinea

January 23, 1942 – August 1945

In the beginning of 1942 the Japanese started their assault on the Australian-held territories of New Guinea Mandate and Papua, and on Western Guinea, which was a part of the Dutch East Indies. In the second phase of the battle, the Allied forces seized the initiative and managed to recapture the lost territories. The campaign in New Guinea lasted until the Japanese surrender in 1945.

1 of 7

Australian units began moving towards Papua’s north coast in July 1942, but the Japanese secured footholds there first, and began to build up forces for an advance over the Owen Stanley mountain range to Port Moresby. The ensuing battles along its only practicable passage, the Kokoda Trail, were small in scale, but a dreadful experience for every participant. Amid dense rainforest, men struggled for footholds, scrambling through deep mud on near-vertical tracks, bent under crippling weights of equipment and supplies; rations arrived erratically and rain almost daily; disease and insects intensified misery.

2 of 7

Ultra decrypts revealed a Japanese plan to land at Milne Bay, on the southeastern tip of the island. An Australian brigade was hastily shipped there and deployed. When the Japanese attempted a night landing, they met fierce resistance, and their survivors were evacuated.

3 of 7

The local Japanese commander was ordered to pull back to the north shore of Papua. The Australians found themselves once more struggling up the Kokoda Trail and across the Owen Stanleys, this time pressing a retreating enemy in conditions no less appalling than during the earlier march.

4 of 7

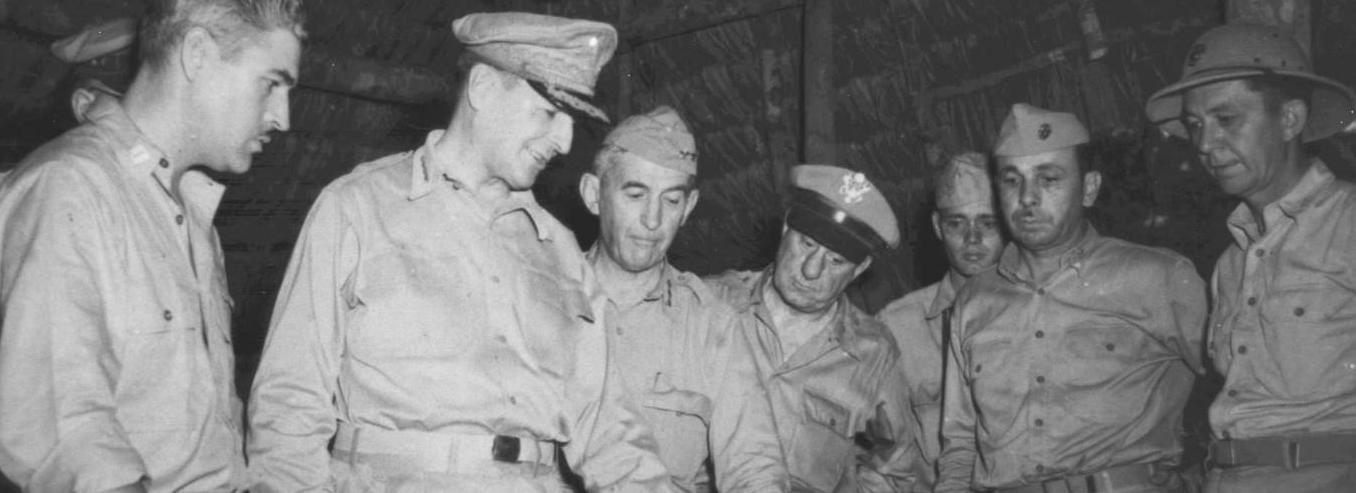

General Douglas MacArthur launched coastal landings by two US regiments, to take Buna. The green Americans, shocked by their first encounter with the combat environment of Papua, performed poorly. Meanwhile, the Australians were exhausted by their efforts on the Kokoda Trail. Thousands of soldiers on both sides were weakened by malaria. But Buna was finally taken at the beginning of January 1943, and residual enemy forces in the area were mopped up three weeks later.

5 of 7

Hard fighting persisted throughout 1943, the battlefields slowly shifting northwards up the huge island. The Japanese, defeated on Guadalcanal, exerted themselves to their utmost to hold a line in New Guinea, feeding in reinforcements. But in March they suffered a crippling blow, during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. George Kenney’s Fifth Air Force, alerted by Ultra, launched a succession of attacks on a Japanese convoy which sank eight transports and four escorting destroyers en route from Rabaul, destroying most of a division intended for Papua New Guinea.

6 of 7

A decisive breakthrough came when Kenney secretly constructed a forward airstrip from which his fighters could strike at the main enemy air bases at Wewak. This they did to devastating effect in August 1943, almost destroying Japanese air power in the region. Thereafter, a force that eventually comprised one US and five Australian divisions launched a major offensive. By September 1943, the major enemy strongholds had been overrun, and 8,000 Japanese survivors were straggling away northwards. The Huon peninsula was cleared in December, and Allied dominance of the campaign became explicit.

7 of 7

Ultra revealed the location of the remaining Japanese concentrations, enabling MacArthur to launch a dramatic operation to bypass them and cut off their escape by landing at Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea in April 1944. Fighting on the island persisted until the end of the war, Australians providing the main Allied effort. Some 13,500 Japanese emerged from the jungle to surrender there in August 1945.

The next phase of the Pacific campaign was driven by expediency and characterized by improvisation. The US, committed to ‘Germany first’, planned to dispatch most of its available troop strength to fight in North Africa. General Douglas MacArthur, in Australia, lacked men to launch the assault on Rabaul which he favored. Instead, Australian troops, slowly reinforced by Americans, were committed to frustrate Japanese designs on the vast jungle island of Papua New Guinea. Separated from the northern tip of Australia by only two hundred miles of sea, this became the scene of one of the grimmest struggles of the war.

1 of 3

Conflict in a hostile natural environment, where amenities and comforts were wholly absent, imposed greater miseries than fighting in North Africa or northwest Europe. But the experience of combat for months on end, prey to fear, chronic exhaustion and discomfort, loss of comrades, separation from domestic life and loved ones, bore down upon every front-line fighter, wherever he was.

2 of 3

With little to show for their commitments in Asia, US military leaders chose to fight Japan where they saw some chance of offensive action. The initiation of South Pacific offensive operations rested on a level of Allied military strength that encouraged caution. In the Southwest Pacific, MacArthur had only two untested American divisions, two Australian divisions, and an Allied air force of 500 aircraft. The Australian-American naval forces had no greater power than the ground and air forces until reinforced by the Pacific Fleet, based in Hawaii and California. The South Pacific theater had one marine division available.

3 of 3

MacArthur recognized that Australia was the Pacific War’s England: an island bastion from which to mount expeditions against the Malay barrier islands all the way to the Philippines. He needed Australian air and ground units to supplement his own forces, and he depended on the enthusiastic commitment of home-front civilians for logistical support. Although he gave its generals no special role, MacArthur understood Australia’s ability to keep a substantial part of the Commonwealth war effort focused on the Pacific. He also often used Australian diplomatic channels to evade the US military chain of command.

Guadalcanal Campaign

After the Japanese defeat at Midway US forces took the initiative and landed on the island of Guadalcanal, a strategic location were the Japanese had built an important airfield. The fighting was brutal. Victory at Guadalcanal enabled the Allies to gain the strategic initiative needed to mount other offensive operations against Japan.

Allied offensives in the Pacific during 1943-44

After the victories at Midway and Guadalcanal in 1942 the US forces gained the initiative over the japanese. Over the next 2 years carefully staged offensives in various island groups in the Pacific were initiated. The American forces and their allies slowly but steadily pushed back the Japanese towards Japan's home islands.

Bombing of the Japanese Islands

During World War Two, and especially after fall 1944 the American air force employed the B29 Superfortress plane to bomb Japanese cities. The Americans targeted industrial centers and military objectives, thus further paralyzing Japan's capacity for war, but residential districts were also targeted.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011