Guadalcanal Campaign

American forces defeat Japan on the Island of Guadalcanal

7 August 1942 - 9 February 1943

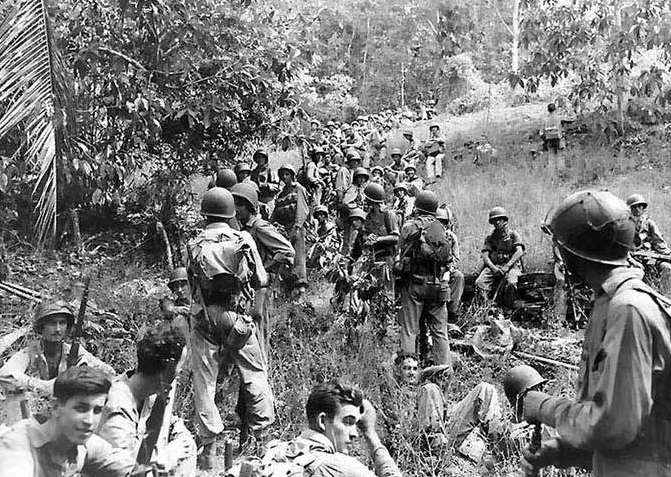

The Guadalcanal Campaign, codenamed Operation Watchtower, was a battle on the Pacific Front of World War Two between the United States and the Japanese Empire. During the battle the American Marines, having learned that the Japanese were attempting to build an airfield in the area that would give them a strategic advantage, landed on Guadalcanal and its surrounding islands. After the Americans captured Henderson Field on the islands in August 1942, the Japanese made several attempts to recapture it over the following months. By December 1942 the Japanese abandoned their efforts to retake the airfield, and evacuated the island by February 1943.

1 of 6

The Japanese defeat at Midway made possible the landings of US forces on the island of Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands in August 1942. This was the first offensive land operation undertaken by the Americans since Pearl Harbor nine months previously.

2 of 6

Instead of attacking simultaneously, which was difficult due to their lack of reinforcements, the Japanese sent in assaults on Henderson Field piecemeal. The Marines managed, through desperate fighting, to ward these off and occasionally to counterattack over the course of the next six months, in a series of operations which often took place at night. These operations were nicknamed the ‘Tokyo Express’ by the Marines who found themselves on the painful receiving end.

3 of 6

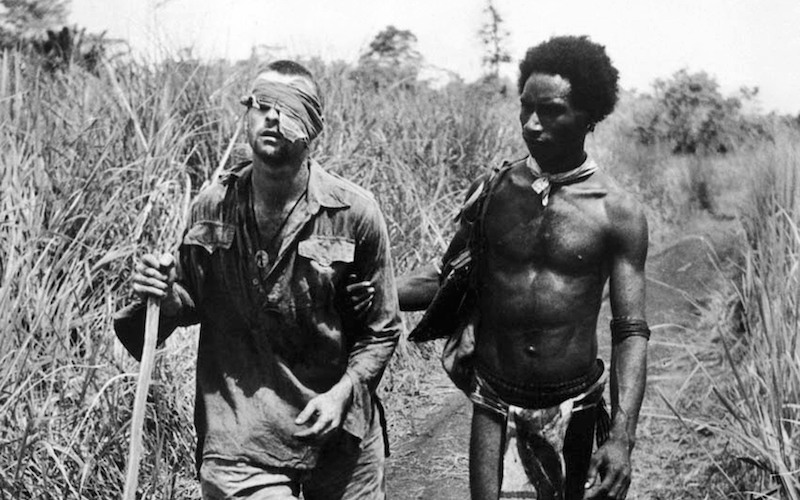

Like New Guinea, the Solomons represented the other end of the discomfort spectrum: volcanic mountains wreathed with tropical rainforests; septic, tepid rivers whose steep, muddy banks made them nature’s moats; rainy coastal jungles with hot, rotting vegetation, home to hostile insects and voracious microbes that feasted on Europeans and Asians alike. The Melanesians in the southern Solomons tended to support the Allies, while those in the northern Solomons did not, but fear and a desire to survive neutralized the behavior of all but a dedicated pro-British few.

4 of 6

The contest for Guadalcanal took on a deadly rhythm that did not change until November 1942, an unbroken cycle of air-sea-land actions that finally brought American victory. This was ‘make see’ war, full of fatal learning. The existence of Henderson Field started the ever-widening vortex of operational requirements. As long as American aircraft could use the field and another constructed nearby, they could attack Japanese reinforcements and protect their own convoys, but only in daylight operations. The Japanese brought ground troops south at night by fast transports and barges to encircle the airfield.

5 of 6

Although malaria in the fetid conditions badly affected the American forces, the Japanese were hit by malaria and severe hunger too. Once the US Navy forced the IJN to withdraw, the Japanese were reduced to releasing drums of supplies from passing destroyers, hoping they would float ashore and be retrieved.

6 of 6

The Japanese kept matching American ground reinforcements until November; they also landed long-range artillery that menaced the air field until the Americans drove them westward with their own heavy artillery and a ground offensive. In the last two months of the campaign, the opposing ground forces attacked the Japanese field force and finally persuaded its commander, Lieutenant General Hyakutake Haruyoshi, to rescue the survivors.

In the Solomons, Japanese soldiers who had occupied Tulagi island moved on to neighboring Guadalcanal, where they began to construct an airfield. If they were allowed to complete and exploit this, their planes could dominate the region. This would have had the effect of interdicting air traffic between the United States and Australia.

1 of 3

Once the major outlines of battle were drawn, the Japanese could do one of three things. They could write off Guadalcanal and concentrate their forces elsewhere. A second possibility open to them was to allocate massive reinforcements, providing sufficient superiority to crush the American forces in the Solomons. The third possible course of action—and the one adopted—was to keep putting more and more resources in, never enough to overwhelm the enemy, culminating only in a salvage operation. This course of action lost Japan the strategic initiative for the second half of 1942.

2 of 3

The setbacks at the Coral Sea and Midway only accelerated plans to assume a strategic defense along the frontier of the 1942 conquests. Japanese intelligence estimated that the Allies would not undertake offensive operations until 1943, a date determined by the arrival of new carriers and battleships for the US Pacific Fleet. On the Asian mainland, the Soviets would remain neutral as they struggled with the Wehrmacht, and the British-Indian army and the Chinese, with their large but poorly trained and badly equipped armies and inadequate air support, could not mount a serious challenge.

3 of 3

The Japanese did indeed have designs on Australia since it provided the Allies with a base from which to attack the Netherlands East Indies and Malaya, essential components of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.

New Guinea Campaign

After the Japanese invasion of New Guinea the Americans, aided by Australian troops, organized a series of landings and other offensive actions against the Japanese in New Guinea. The long and arduous campaign was over when the Japanese forces surrendered in August 1945.

Allied offensives in the Pacific during 1943-44

After the victories at Midway and Guadalcanal in 1942 the US forces gained the initiative over the japanese. Over the next 2 years carefully staged offensives in various island groups in the Pacific were initiated. The American forces and their allies slowly but steadily pushed back the Japanese towards Japan's home islands.

Bombing of the Japanese Islands

During World War Two, and especially after fall 1944 the American air force employed the B29 Superfortress plane to bomb Japanese cities. The Americans targeted industrial centers and military objectives, thus further paralyzing Japan's capacity for war, but residential districts were also targeted.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011