Allied offensives in the Pacific during 1943-44

Allied advances in the Pacific

After the American victories at Midway and Guadalcanal, the tides of war in the Pacific turned against Japan. Due to America’s overwhelming military and industrial capabilities, the Allied forces gained the upper hand. Over the next two years the Japanese suffered a series of military setbacks, losing many of the islands they had conquered. The Allied military leaders often adopted a policy of ‘island hopping’, bypassing Japanese strongholds that had a strong presence, but were isolated and could not be reinforced. This strategy was adopted so that the Allied soldiers could be rested for the islands that the Japanese could reinforce.

1 of 4

There was no scope for strategic deception, because the only credible objectives for American assault were a handful of island air bases. The US Navy and Marine Corps advanced from one foothold to the next, knowing that the Japanese had fortified them all in anticipation of their coming.

2 of 4

US dominance of air and sea had become so great that Japanese forces in the southwest Pacific were incapable of transporting enough troops to threaten Allied strategic purposes. In late 1943 US submarines, decisive contributors to victory, began to wreak havoc upon Japan’s supply links to its over-extended empire. Many Japanese island garrisons were starved of weapons and ammunition as well as food.

3 of 4

How that ultimate defeat was to be achieved was certainly not yet obvious in 1943. The offensives were pushed, nevertheless, not only because the commanders on the spot were insistent on doing so but because there were excellent reasons for believing it was essential to keep the Japanese on the defensive lest they so fortify the islands and build up the air bases on them as to make a deferred assault horrendously costly or even impossible. It would all prove difficult enough as it was.

4 of 4

The broad outlines of American strategy in the Pacific had been agreed upon at the Quadrant Conference in Quebec in August 1943. There it had been formally decided that the Central Pacific thrust would head for the Marianas, while in the Southwest Pacific the aim was the Vogelkop peninsula, the northwest corner of New Guinea. From these positions, an invasion of the Philippines as well as other alternatives would be open.

At the January 1943 Casablanca summit conference, the Western Allied leaderships reasserted the priority of defeating Germany, but agreed to devote sufficient resources to the war against Japan to maintain the initiative. The US Navy and Marine Corps were unfailingly sceptical about southwest Pacific operations, directed towards ultimate recapture of the Philippines. The admirals preferred instead to thrust across the central Pacific through the Marshall, Caroline and Mariana islands, the shortest route to Japan. A decision was taken to undertake both simultaneously. The British, meanwhile, addressed themselves once more to Burma.

1 of 5

The USAAF was unwilling even to allocate long range bombers to conduct a major air offensive against Japan’s key base in the south-west Pacific, Rabaul, before 1944. The chiefs of staff thus agreed that in 1943 Allied forces would pursue modest objectives: advancing up the Solomons to Bougainville, while MacArthur’s forces addressed the north coast of New Guinea. The latter was an exclusive US Army and Australian operation, though dependent on naval support.

2 of 5

The Americans in looking toward 1943 in the Pacific concentrated on projects to improve their position for action in subsequent years when more force would be available. As much Japanese shipping as possible was to be sunk by Allied submarines and planes, and steps would be taken to seize bases closer to Japan from which that country itself could be bombed, and also its shipping routes. The issue of a landing assault on the Japanese home islands was at this time left open, but the same operations which brought them within land-based airplane range would in any case be needed for such an assault.

3 of 5

Nothing could alter the campaign’s fundamentals: to defeat Japan, US forces must seize strongly defended Pacific air and naval bases. No application of superior technology and firepower could avert the need for American soldiers and Marines to expose their bodies to a skilful and stubborn foe. Even though it was plain that the Allies would win the war, Japan’s commitment remained unshaken.

4 of 5

Implementation of the plan for the central Pacific thrust would be enormously aided by the fact that the warships ordered under the Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940 were coming out of the construction yards into the navy during 1943. In this regard, the hopes of the Americans and the apprehensions of the Japanese concerning that great program proved to be well founded.

5 of 5

It has been argued that the double thrust, which was designed partly by default to accommodate the army-navy rivalry of MacArthur and Nimitz, should have been replaced by one single thrust regardless of the problems posed by the personalities involved. However there was also much to be said for allocating the steadily growing American forces to two axes of advance, which would be able to assist each other. The advantage was seen when the Japanese, struggling already with shrinking resources, were unable to block one of the thrusts without taking troops from the other, leaving a gap for the Allied forces to push through.

Guadalcanal Campaign

After the Japanese defeat at Midway US forces took the initiative and landed on the island of Guadalcanal, a strategic location were the Japanese had built an important airfield. The fighting was brutal. Victory at Guadalcanal enabled the Allies to gain the strategic initiative needed to mount other offensive operations against Japan.

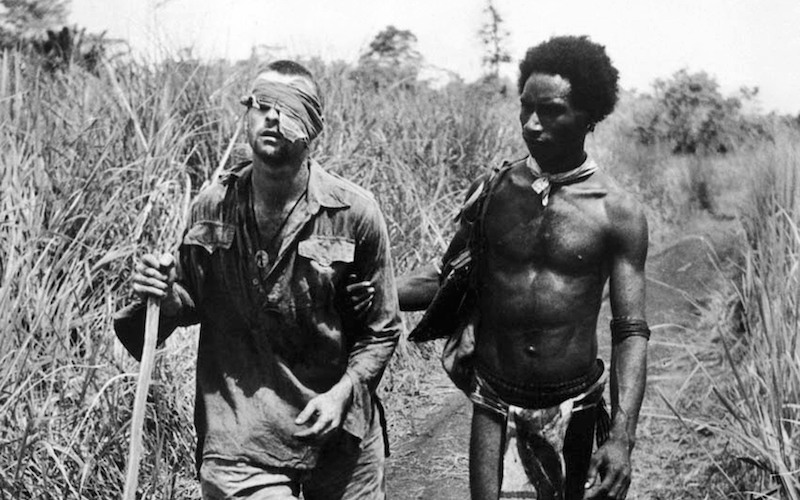

New Guinea Campaign

After the Japanese invasion of New Guinea the Americans, aided by Australian troops, organized a series of landings and other offensive actions against the Japanese in New Guinea. The long and arduous campaign was over when the Japanese forces surrendered in August 1945.

Bombing of the Japanese Islands

During World War Two, and especially after fall 1944 the American air force employed the B29 Superfortress plane to bomb Japanese cities. The Americans targeted industrial centers and military objectives, thus further paralyzing Japan's capacity for war, but residential districts were also targeted.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011