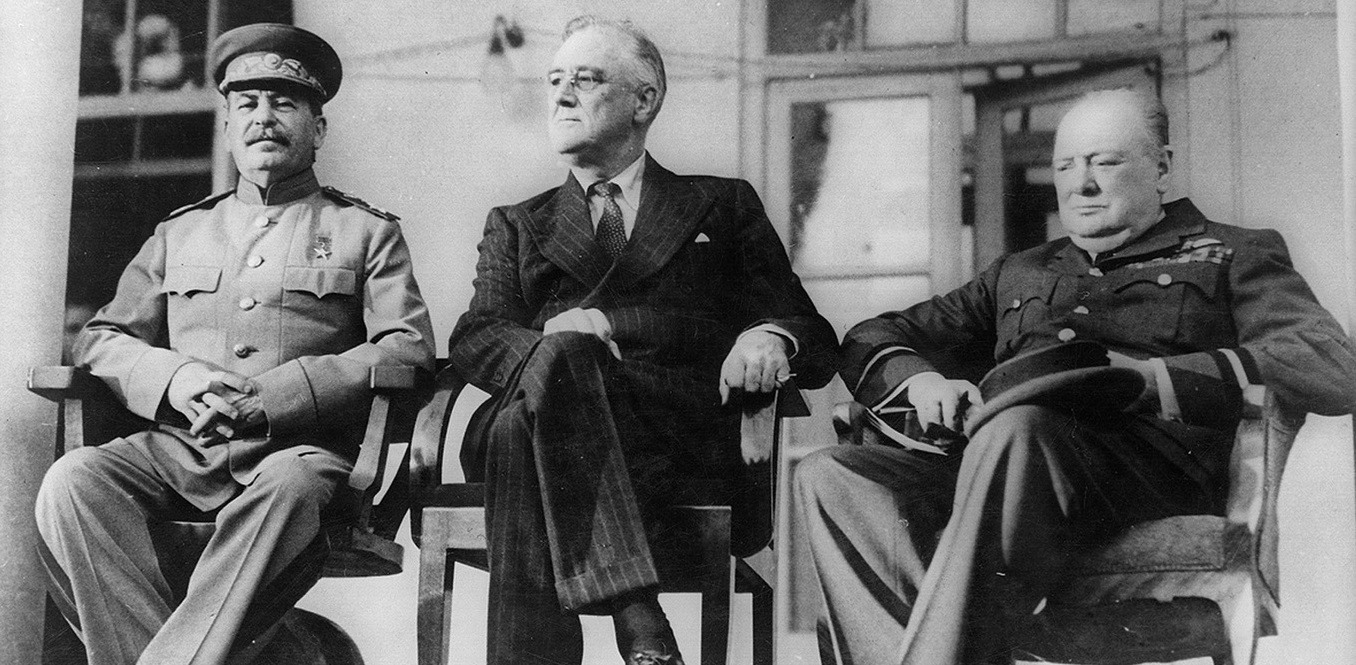

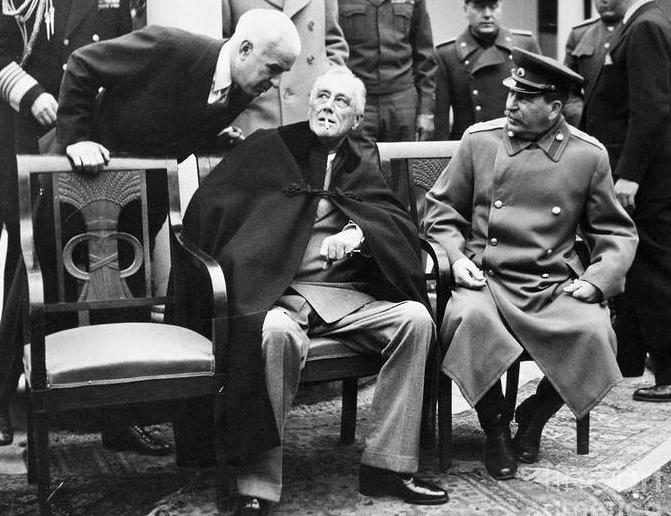

Yalta Conference

Some nations sacrificed for the sake of stability

4 - 11 February 1945

The Yalta Conference was an inter-Allied meeting to discuss Germany and the reorganization of post-war Europe. During the meeting, US President Franklin D. Roosvelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin met near Yalta, Crimeea. Roosevelt certainly tried everything – including straightforward flattery – to try to bring Stalin round to a reasonable stance on any number of important post-war issues, such as the creation of a meaningful United Nations, but he overestimated what his charm could achieve.

1 of 3

By the time of Yalta, it was Roosevelt who was making all the efforts to keep the alliance together. With the Red Army firmly in occupation of Poland, and Soviet divisions threatening Berlin itself when the conference opened, there was effectively very little that either FDR or Churchill could have done to safeguard political freedom in Eastern Europe, and both knew it.

2 of 3

Of more immediate concern to both Britain and the United States was the impact of the Yalta agreements on the Polish corps fighting in Italy and the Polish division in Montgomery's forces on the Western Front. Would these men, who were still very much needed by the Allies, continue to participate as valiantly as in the past, in a cause that must have looked already irretrievably lost to most of them? In anxious talks and soundings between the two parties, it became clear that until victory over Germany, the Polish soldiers would indeed continue to fight alongside the Western Allies.

3 of 3

The Allied occupation zones had been agreed many months earlier, and confirmed at the Yalta summit in February. The Russians got to Eastern Europe first. To have frustrated their imperialistic purposes, it would have been necessary for the Western Allies to fight a very different and more ruthless war, at much higher cost in casualties. They would have had to acknowledge the possibility, even the probability, of overcoming the Red Army as well as the Wehrmacht. Such a course was politically and militarily unthinkable.

The Allied leaders met in a series of sessions which have gained more fame — or notoriety — than perhaps they deserve. Most of the major diplomatic choices were prefigured at the Tehran Conference, and the most contentious political issue between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies — the fate of Poland and Southeast Europe — had been effectively settled between Tehran and Yalta by the occupation — or liberation — of practically the whole of that area by the Red Army in the interim. If one major factor overshadowing the Yalta deliberations was the control which the Soviet Union in fact already exercised over almost all of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the other side of the coin was the British control of Greece, and American and British predominance in Italy, France, and most of the Low Countries.

1 of 6

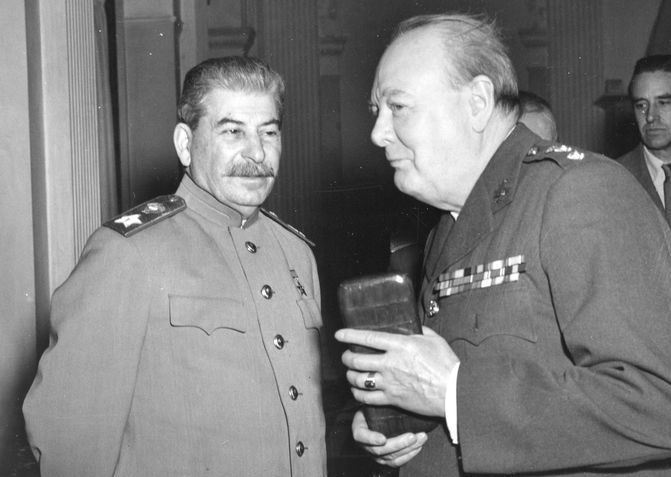

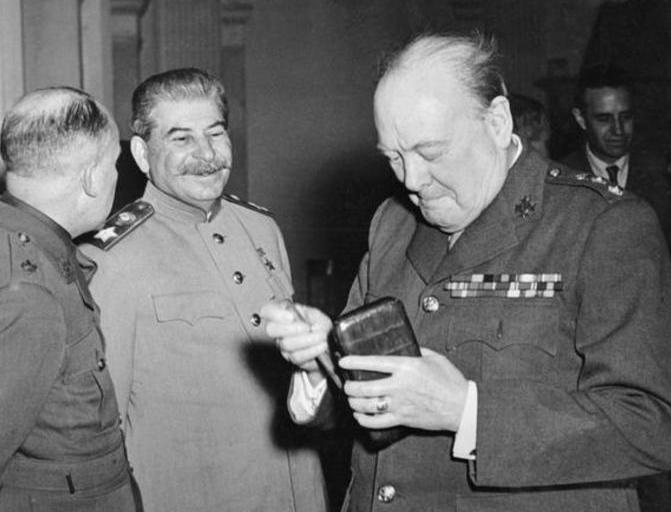

A far more realistic approach to dealing with Stalin had been adopted by Churchill in Moscow in October 1944, when he took along what he called ‘a naughty document’ which listed the ‘proportional interest’ in five south-east European countries. Greece would be under 90 percent British influence ‘in accord with the US’ and 10 percent Russian; Yugoslavia and Hungary were 50-50; Romania would be 90 percent Russian, 10 percent British; and Bulgaria 75 percent Russian and 25 percent ‘the others’. Stalin signed the document with a big blue tick, telling Churchill to keep it, and generally stuck to the agreements.

2 of 6

The conference made it plain that, following victory, a communist government would rule Poland, and that the east of the country would become Russian soil. By the time of the meeting at Yalta, the ‘Lublin Committee’ was installed in Warsaw, and already the Czechoslovak government-in exile had followed Soviet wishes by recognizing it, not the London government-in-exile, as the legal regime of its northern neighbor.

3 of 6

The Americans and British found that they would get very little in the way of concessions regarding the government of Poland, and the concessions which they did obtain were quickly repudiated soon after the meeting: the expansion of the Lublin regime by representatives of the London government-in-exile and others from within Poland was quickly and effectively sabotaged, while the free elections, which Stalin promised could be held as early as a month off, were not held until 1989, forty-four years later.

4 of 6

The Poles clung to vestigial hopes that their fighting contribution to the Allied cause might yet make possible some modification of the Yalta terms in their favor. But the reality, of course, was that each of the conquering nations would arbitrate the future of the countries it occupied in the fashion that it deemed appropriate. Stalin’s soldiers were already in Poland, for which Britain and France had gone to war, while the Western armies were far away.

5 of 6

Since the Soviet Union had not interfered in the fighting between the British and the Greek Communists when the latter had attempted to seize power, Stalin may have felt entitled to repress all opposition in the area controlled by his army, although agreeing to the American proposal of a declaration assuring all liberated and occupied territories the freedom to choose their own government. The Soviet Union wanted ‘friendly’ regimes in East and Southeast Europe, and there was no way that governments which Stalin considered friendly were likely to emerge from free elections.

6 of 6

Getting the American public to accept the compromises the Western Powers had made on Poland was going to be difficult. Both the British and Americans agreed to an eastern border for Poland based on the Curzon Line — as they had previously indicated they would at Tehran — but Roosevelt did try very hard, though unsuccessfully, to salvage the primarily Polish city of Lwów as well as the nearby oil fields for Poland.

Tehran Conference

The Tehran conference was organized to resolve problems concerning the progress of the Second World War and the organization of the post-war world, following the Allied victory.

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was a meeting organized by the victorious Allied Powers of the Second World War, which aimed to reinstate order to the world after the end of the war. It revealed the existence of a Cold War between the two camps, the Soviet and English-American.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011