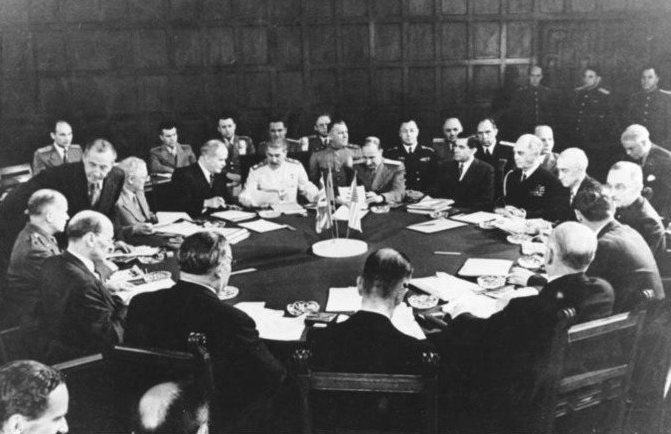

Potsdam Conference

First sign of the Cold War

17 July - 2 August 1945

The Potsdam Conference was the longest of the Allied wartime conferences. The French did not participate, as both the Soviet and American governments saw no reason to invite them. Many of the agreements reached on the German question would subsequently founder on French opposition. The French government did not feel bound by decisions in which it had not participated, and French vetoes quickly blocked the implementation of those portions of the Potsdam agreements which called for the administrative and economic unity of Germany. The question of Germany, however, was but one of two dominating the conference; the other was the continued war with Japan. The Americans as well as the British wanted a timely entrance of Russia which would tie down the Japanese forces in Manchuria and northern China. The ... Soviet Union would enter the Pacific War on the 15th of August 1945.read more

1 of 4

The weakness of France was a key factor; in Soviet eyes this was a minor Western satellite whose presence would have called for the admission of a Soviet satellite, perhaps Poland, which in turn would have caused problems for Britain and the United States. The Americans had no enthusiasm for the French either.

2 of 4

Truman went to Potsdam in July to meet Stalin and Churchill; the latter was replaced mid-conference by the Labour Party leader, Clement Attlee. Stalin showed no special remorse over FDR’s and Churchill’s absence, and he did not react when Truman hinted that the United States had a ‘super bomb’.

3 of 4

President Truman went to Potsdam determined by the advice of American military leaders and his own inclination to obtain an early entrance of the Soviet Union into the war in the Pacific. He had approved the invasion of Kyushu and was aware of the large anticipated cost in casualties. Stalin had previously promised to enter the war against Japan, but for Truman, as for Roosevelt, the critical issue was one of timing.

4 of 4

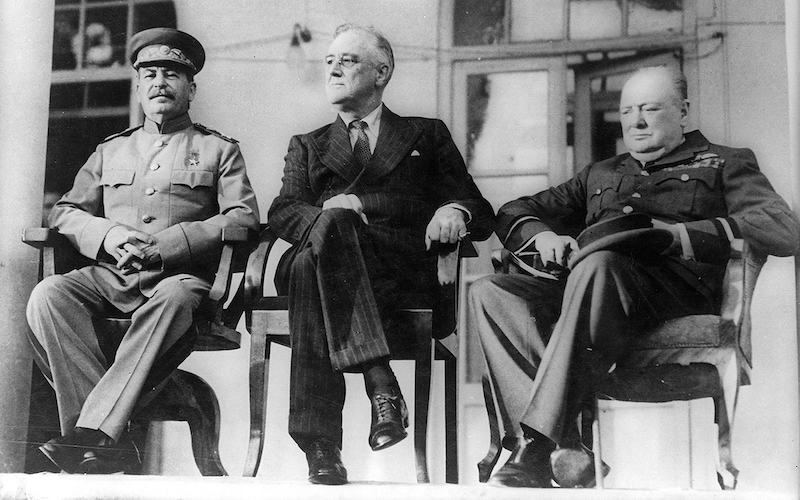

With the end of the German war, the time had come for a concentration on the Pacific. When the three leaders had met at Yalta, in February 1945, a bargain had been struck, to the effect that when the war in Europe ended, the USSR would break the nonaggression agreement with Japan and declare war. In return, Stalin was handed control of Europe east of the Elbe. The Americans did not of course want the Soviet Union in China, let alone Japan, but they did not want to have to reduce Japan on their own.

There were three practical issues about Germany facing the Potsdam Conference. One was the establishment of a government machinery, the second was that of borders, and the third reparations. On the first, agreement was reached on an administration which would be directed and controlled by an Allied Control Council (ACC), with each zonal commander able to act on his own if no agreement or policy were reached. Because of Soviet insistence, the future border between Poland and Germany was fixed on the western Neisse, actually turning that area, along with the rest of eastern Germany (except for northern East Prussia) over to Polish administration. The Soviets also wanted massive reparations.

1 of 5

The recently deceased President Roosevelt had predicted with considerable accuracy the basic nature of the problems which the Allies faced. He had expressed dislike for ‘making detailed plans for a country which we do not yet occupy’ and had repeatedly based this reluctance on the inability to predict ‘what we and the Allies find when we get into Germany’. It turned out that the Allies found a Germany without government or administration, but with massive destruction, misery, and dislocation. As for what they could do about it, another prediction of Roosevelt's proved to be correct: ‘In regard to the Soviet government... we have to remember that in their occupied territory they will do more or less what they wish. We cannot afford to get into a position of merely recording protests on our part unless there is some chance of some of the protests being heeded.’

2 of 5

The British and the Americans were still a little reluctant to agree to such enormous territorial and population transfers, and they argued that there was no way to reconcile such a procedure with reparations from the over-burdened western zones. A compromise, suggested by the new United States Secretary of State James Byrnes, was eventually agreed upon. The Western Allies agreed to Soviet action in transferring the territory east of the Oder and western Neisse to Polish administration while reserving final border settlement to the peace conference: they had in reality accepted the new border as permanent in fact if not in law. In return, it was agreed by all that the Soviet Union would satisfy its reparations needs primarily out of its zone of occupation.

3 of 5

Since the French vetoed the establishment of a common central German administrative apparatus and the four ACC representatives rarely agreed on policy, this really ended up meaning that each zone would go its own way. Dismemberment had been rejected in theory but was put into effect in practice.

4 of 5

The British, who had the zone with the greatest food deficit, insisted on food deliveries from the eastern zone so that the German workers could be fed; the Americans were sure, on the basis of their reading of the post-World War I experience, that they themselves would end up paying for the reparations as they paid to keep the Germans in all three western zones from starving.

5 of 5

The Soviet Union insisted on heavy reparations, very reasonably arguing that the terrible destruction wrought by the German invasion of their territory should be repaid as much as possible by German labor, German machinery, and German goods; the United States, on the other hand, was reluctant to endorse forced labor and could not see how goods for reparations could be produced by a wrecked economy and hungry people.

Tehran Conference

The Tehran conference was organized to resolve problems concerning the progress of the Second World War and the organization of the post-war world, following the Allied victory.

Yalta Conference

The most important meeting between the three leaders happened in Yalta. The Yalta Conference is even now fiercely debated and analyzed. It had the most complex repercussions on post-war Europe.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Norman Stone, World War Two: A Short History, Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, New York, 2012