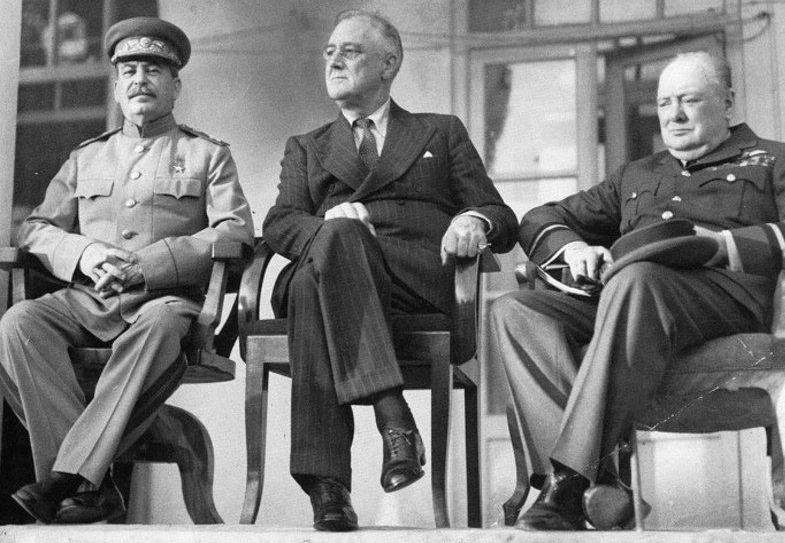

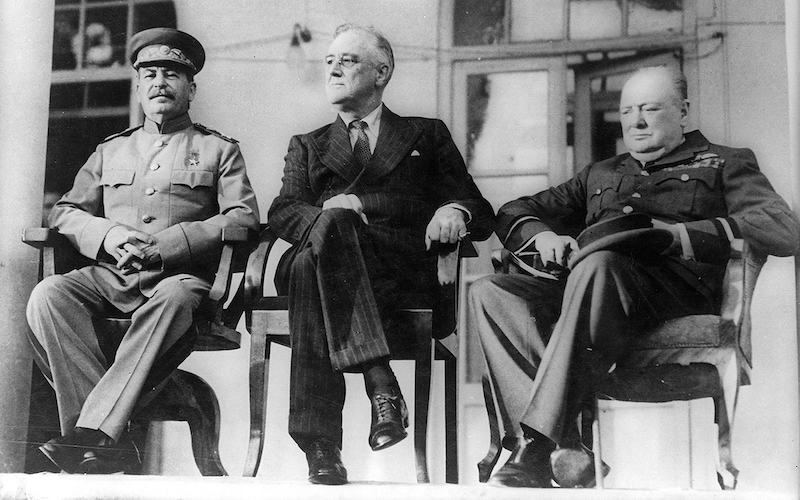

Tehran Conference

First meeting of The Big Three

28 November - 1 December 1943

The Tehran conference was the first meeting of what became known as the Big Three: US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The conference, held inside the Soviet embassy in Tehran, addressed the all-important issue of opening up a second front in Europe in order to relieve pressure on the Eastern Front.

1 of 4

Roosevelt was under the mistaken but surprisingly widespread impression that personal intercourse could mollify Stalin, and he deliberately set out to try to charm the Russian dictator, if necessary by making Churchill the butt of his teasing. For his part, Stalin insisted on the invalid Roosevelt flying halfway around the world to meet in the Iranian capital, and placing him in the Russian Legation as his guest, thus separating him from Churchill.

2 of 4

With so much time spent on military strategy, there was not much left for political issues. Roosevelt spoke up for Finland (with which the United States was not at war), and Stalin explained that the Soviet Union did not wish to annex it, would insist on the 1941 border but might trade Hangö for Petsamo, and would expect the Finns to drive out the Germans during the war and pay reparations in kind afterwards.

3 of 4

As for the Soviet interest in acquiring the northern portion of East Prussia with the port city of Königsberg (with the southern part going to Poland), this was agreeable to the British and Americans, who had been convinced by the incessant German propaganda of the inter-war years that Germans could not live on both sides of Poles, and who were therefore certain that East Prussia should never be returned to Germany.

4 of 4

At Tehran it was agreed that Poland should be shifted to the west, losing roughly the same territories given to the USSR in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and being compensated in the west from German industry-rich territory; in time, five million Poles would be deported from east to west. The extension of Soviet influence to other lands became ever more likely, with Churchill’s connivance.

Less happy was the reception given to Churchill’s strategy of using Italy as a springboard from which to attack the Germans in south-eastern France, Austria and Hungary via Yugoslavia. Not wishing to see a powerful Allied force in his south-eastern European backyard, Stalin opposed the scheme, and was supported by Roosevelt, so it fell through, much to Churchill’s chagrin. Although Stalin would have preferred to see an earlier date for the cross-Channel invasion, he accepted that it would take place on 1 May 1944. It later had to be put back five weeks for lack of landing craft, after fighting in Italy went on for longer than planned.

1 of 3

The insistence of Churchill on repeatedly returning to the charge on extended operations in the Mediterranean and delays in Overlord meant that most of three of the four days at the Tehran Conference were taken up with arguments over strategy in the European war, although Stalin made his own preference absolutely clear at the very first meeting. Whatever may have caused him to consider further Mediterranean operations earlier, he now insisted that all be subordinated to Overlord in May 1944, with that operation to be accompanied and preferably preceded by a landing on the southern coast of France. A Soviet offensive would be coordinated with the invasion.

2 of 3

The British feared that an invasion attempt might fail, and for them, that would be the end of the road. They had been driven off the continent by the Germans three times in the war; the fourth time would be fatal. The Americans, on the other hand, certainly hoped and expected that the invasion would succeed; but if it did fail, they could and they would try again. The Russians undoubtedly felt that, success or failure, it was about time the Western Powers did their share of the fighting in Europe.

3 of 3

At Stalin's insistence that the operation would never be launched unless a Commander-in-Chief were appointed for it, the President promised that this would be done within a few days. Since the British had blocked an overall European command, he decided right after the Tehran Conference to keep General George Marshall in Washington and appoint Dwight Eisenhower.

Yalta Conference

The most important meeting between the three leaders happened in Yalta. The Yalta Conference is even now fiercely debated and analyzed. It had the most complex repercussions on post-war Europe.

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was a meeting organized by the victorious Allied Powers of the Second World War, which aimed to reinstate order to the world after the end of the war. It revealed the existence of a Cold War between the two camps, the Soviet and English-American.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Norman Stone, World War Two: A Short History, Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, New York, 2012