Western Desert Campaign until the Fall of Tobruk

British and Axis forces battle for control of Libya and Egypt

9 September 1940 - 21 June 1942

The campaign in North Africa’s Western Desert began with the Italian invasion of Egypt, a British protectorate at the time. Afterwards the British launched Operation Compass, a raid that led to the destruction of the Italian 10th Army. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini sought help from his German allies. Thus, the German Afrika Corps was formed, which, under the command of Erwin Rommel, launched a campaign that pushed the British back from Libya, into Egypt, and up to the port of Tobruk, which was besieged until relieved by the British during Operation Crusader. The Axis forces managed to regroup and take Tobruk during the Battle of Gazala, but failed to obtain a decisive victory.

1 of 4

In two months, the Western Desert Force had achieved resounding successes; they had destroyed nine Italian divisions and part of a tenth, advanced 500 miles and captured 130,000 prisoners, 380 tanks and 1,290 guns, all at the cost of only 500 killed and 1,373 wounded. In the whole course of the campaign, Archibald Wavell, the British commander, never enjoyed a force larger than two divisions, with only one of them armored. It was the Austerlitz of Africa, and prompted his prep school to note in the Old Boys’ section of the Summer Fields magazine: ‘Wavell has done well in Africa.’

2 of 4

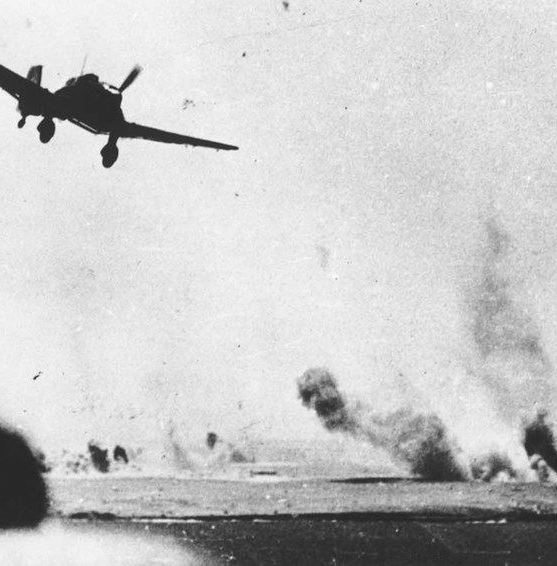

Lieutenant-General Henry ‘Jumbo’ Maitland Wilson took a large number of troops from the western desert to Greece under orders from Churchill. This was an error when the Mediterranean theater was still far from safe. As an assistant secretary to the War Cabinet, Lawrence Burgis noted in April 1941, when ‘a terribly important convoy of tanks destined for Egypt was about to risk the perilous Mediterranean route, the PM informed the Cabinet of the timetable, adding: “If anyone’s good at praying, now is the time.”’

3 of 4

Faced with the defeat of fascism in Africa, Hitler decided to try to save his ideological soulmate, Benito Mussolini, in Africa (and later in Greece), even though his strategy dictated that neither place would be the key to the victory he sought, which was always going to be in Russia.

4 of 4

In the long term, Germany’s explosion into the Mediterranean theater weakened the war effort against Russia in ways that could not have been predicted in the spring of 1941. It drew off German strength from the war’s main theater. In 1943 the invasion of Sicily meant that Luftwaffe units had to be brought down from Norway where they had been threatening the Murmansk route. In the short run, however, Germany won significant victories, and expected more.

The first of several British commanders in the long Western Desert campaign was Archibald Wavell, a fine example of the British Army officer of the old school. He was also the most literary and reflective of Britain’s Second World War generals. Yet there were always severe personality differences between Wavell and Churchill, amounting at times to mutual detestation. Even though Wavell had supported the creation of Ralph Bagnold’s Long Range Desert Group in North Africa, Churchill thought him too cautious and conventional a commander, and wanted to replace him.

1 of 3

Wavell’s family came to Britain with William the Conqueror, both his father and grandfather had been generals, he had had a brilliant school career and was personally brave in action. A natural sportsman, captain of the regimental hockey team, a fine shot, an excellent linguist (Urdu, Pashto and Russian), he served in the Boer War and on the North-West Frontier and entered Camberley Staff College in 1909 with an 85 percent exam pass. He married a colonel’s daughter called Queenie, of whom he wrote admiringly to a friend: ‘She rides well to hounds.’

2 of 3

Much to his chagrin, Wavell was stuck at the War Office when the rest of the Army decamped to France and Flanders in August 1914. Although he did later see action, Wavell spent most of the Great War as a liaison officer with the Grand Duke Nicholas’ army in Turkey, later serving under General Allenby in Palestine. He not only distinguished himself, but got to know the Middle East and was sent out to command in Palestine in 1937-8.

3 of 3

When in August 1940 Wavell returned to London to brief the War Cabinet’s Middle East Committee, Anthony Eden thought his account of operations ‘masterly’, but Churchill’s curt cross-questioning left him feeling bruised and insulted. Nonetheless, great risks were run in Africa that month, virtually denuding Britain of tanks while the country was still under threat of invasion, in one of the toughest decisions of the war.

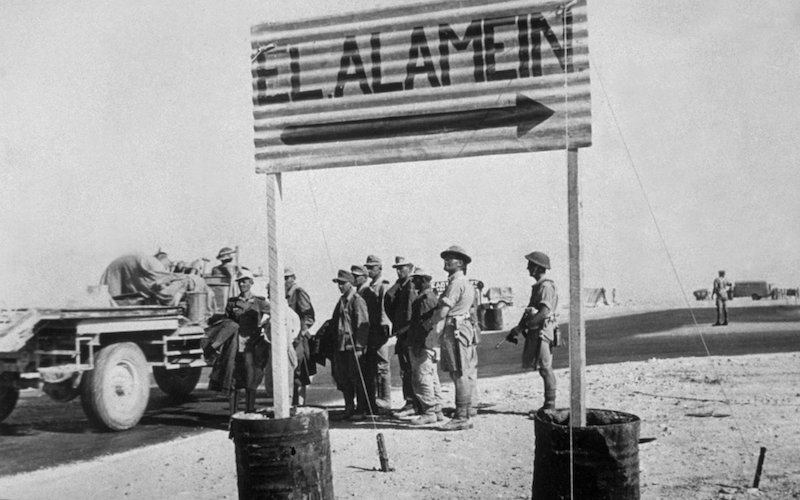

Battles of El Alamein

El Alamein was a decisive victory in the African campaign for the Allies. Winston Churchill affirmed: “We can almost say that before Alamein, we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat”.

Operation Torch

Operation Torch was the name given to the Allied invasion of French North Africa . Operation Torch was the first time the British and Americans had jointly worked on an invasion plan together.

Tunisian Campaign

After the Axis defeat at El Alamein General Erwin Rommel's forces were forced to retreat across Libya, and into Tunisia, with the British forces perusing them. After another series of events the German-Italian collapse was inevitable: pressed from both sides their defenses crumbled by spring 1943 and were forced to surrender.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000