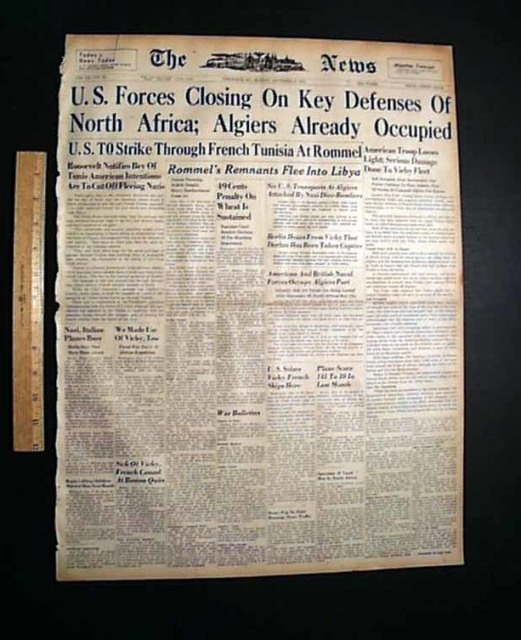

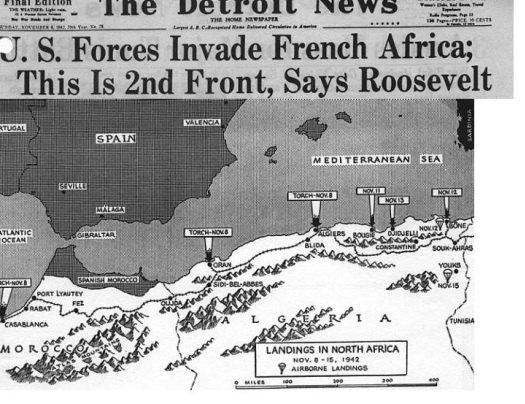

Operation Torch

British and American forces land in Marocco and Algeris

8 - 10 November 1942

Operation Torch was the name given to the Allied invasion of French North Africa . Operation Torch was the first time the British and Americans had jointly worked on an invasion plan together.

1 of 7

Though American military commanders were confident about a successful landing in France at the time, the British got their way when Roosevelt supported Churchill’s request that the Allies prepare for the French North African option.

2 of 7

From North Africa, the plan was to invade Sicily and then on to mainland Italy and move up the so-called “soft underbelly” of Europe. Victory in the region would also do a great deal to clear the Mediterranean Sea of Axis shipping and leave it more free for the Allies to use.

3 of 7

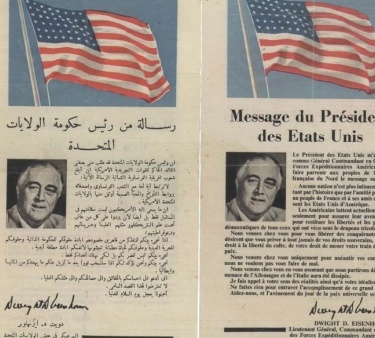

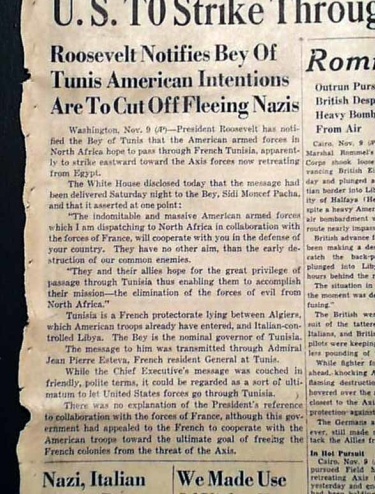

The Allies planned to invade Morocco and Algeria. Both these countries were under the nominal rule of Vichy France. As the Vichy government in France was seen by the Allies to be in collaboration with Nazi Germany, both North African states were considered to be legitimate targets. There were about 60,000 French troops in Morocco with a small naval fleet based at Casablanca. Rather than fight the French, plans were made to gain the cooperation of the French army. General Eisenhower was given command of Operation Torch and in the planning phase he set up his headquarters in Gibraltar.

4 of 7

An American consul based in Algiers, Robert Daniel Murphy, was tasked with sounding out how cooperative the French army would be. Before the landings a senior American general, Mark Clark, was sent by submarine to Cherchell to meet with senior French army officers based in French North Africa.

5 of 7

The landings started before daybreak. There was no preliminary air or naval bombardment as the Allies hoped that the French based at the three landing zones would not resist the landings. French coastal batteries did fire at transport ships but Allied naval gunfire retaliated. However, French sniper fire proved more difficult to resolve. Carrier-based planes were needed at the landing beaches to deal with the unexpected and unwanted French resistance. The resistance put up by the French was more an inconvenience as opposed to a major military problem.

6 of 7

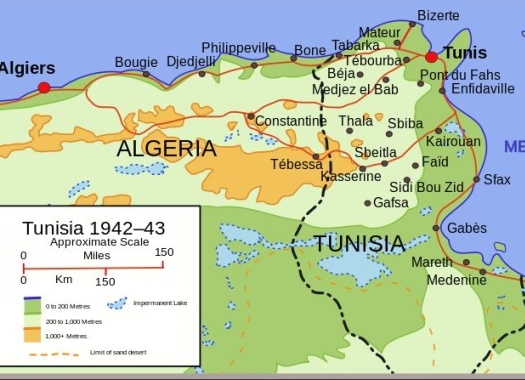

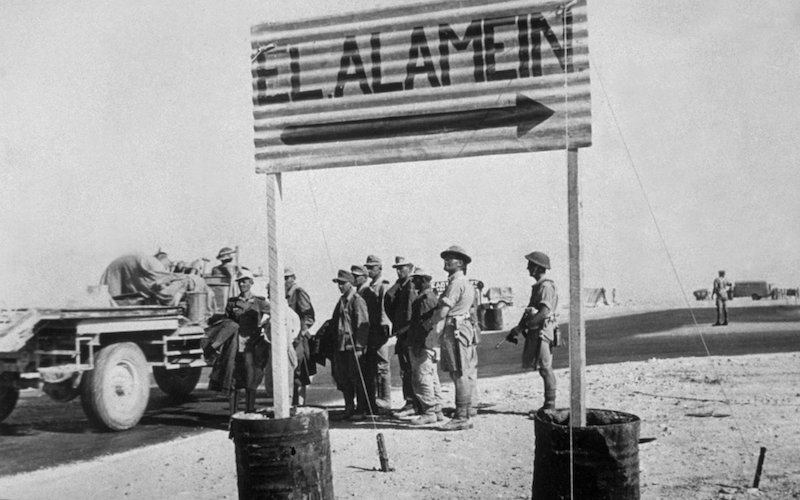

The landings at all three beaches were highly successful. French resistance had been minimal as were Allied casualties. After consolidating their forces, the Allies moved out into Tunisia. After Montgomery’s success at El Alamein, the Afrika Korps was in retreat. However, the further it moved west from El Alamein, the nearer it got to the recently landed Allied troops.

7 of 7

Though damaged, the Afrika Korps was still a potent fighting force as the Allies found out at Faid Pass and at the Kasserine Pass. However, the might of two advancing Allied armies meant that it was trapped and so the Afrika Korps surrendered. Whether the surrender would have come about so quickly without the success of Operation Torch is open to question.

Stalin’s Russia had been pressing the Allies to start a new front against the Germans in the western sector of the war in Europe. At the time of the Torch landings the British did not feel strong enough to attack Germany via France. But the victory at El Alamein was a great stimulus to the Allies to attack the Axis forces in North Africa.

1 of 7

American strategic thinking before the landings aimed at defeating Nazi Germany before turning to the problems that a flood of Japanese conquests and victories were raising in the Pacific. General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army’s chief of staff, viewed the strategic problem in simple terms: The United States should concentrate its military might on achieving a successful lodgment on the European continent as soon as possible.

2 of 7

The plight of the Soviet Army seemed desperate, as Adolf Hitler’s Panzer divisions pushed ever onward toward Stalingrad and the Caucasus. Some American military planners believed that it might be necessary to invade northwestern Europe in 1942 to take the heat off the hard-pressed Soviets. But their preferred date was spring 1943, when American ground forces would be better prepared, trained and equipped to fight the Wehrmacht on the European continent. Whatever the difficulties of such an operation, they believed that American know-how and resources could solve them.

3 of 7

British military leaders, led by the formidable chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Alan Brooke, took a very different approach. They were not at all optimistic about a cross-Channel amphibious operation in 1943, and they were completely against launching such an operation in 1942. Part of their opposition lay in the fact that the United Kingdom would have to bear much of the military burden for such an attempt.

4 of 7

Britain’s military leaders had experienced the vicious fighting against the Germans in World War I that had inflicted such heavy casualties on their forces. Most of them had also confronted the Wehrmacht’s formidable fighting power during the disastrous campaign in France in World War Two, while the experiences of British forces in North Africa and Libya against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had done nothing to diminish their respect for German military capabilities.

5 of 7

After the war, Brooke put the situation in these terms: ”I found Marshall’s rigid form of strategy very difficult to cope with. He never fully appreciated what operations in France would mean — the different standard of training of German divisions as opposed to the raw American divisions and to most of our new divisions. He could not appreciate the fact that the Germans could reinforce the point of attack some three to four times faster than we could, nor would he understand that until the Mediterranean was open again we should always suffer from a crippling shortage of sea transport.”

6 of 7

The British staunchly opposed any amphibious landing in Europe. Instead, they urged the Americans to consider the possibility of intervening in the Mediterranean to clear Axis military power from the shores of North Africa and open up that great inland sea to the movement of Allied convoys. The result was a deadlock, one that led Marshall to consider for a short period switching the U.S. Army’s emphasis from the European Theater of Operations to the Pacific. However, President Roosevelt refused to hear of any such change in U.S. grand strategy.

7 of 7

Roosevelt did something that Winston Churchill was never to do during the entire course of World War II. He intervened and overruled his military advisers. Roosevelt gave his generals a direct order to support the British proposal for landings along the coast of French North Africa. The president’s reasoning was largely based on political necessity. If Germany remained the main focus of the American war effort then U.S. troops were going to have to fight against the Germans somewhere in Europe. Given British attitudes, there was no choice but to move against North Africa and thus commit U.S. forces to the battle for control of the Mediterranean.

Western Desert Campaign until the Fall of Tobruk

The campaign in North Africa’s Western Desert began with the Italian invasion of Egypt, a British protectorate at the time. Afterwards the British launched Operation Compass and italian dictator Benito Mussolini sought help from his German allies.

Battles of El Alamein

El Alamein was a decisive victory in the African campaign for the Allies. Winston Churchill affirmed: “We can almost say that before Alamein, we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat”.

Tunisian Campaign

After the Axis defeat at El Alamein General Erwin Rommel's forces were forced to retreat across Libya, and into Tunisia, with the British forces perusing them. After another series of events the German-Italian collapse was inevitable: pressed from both sides their defenses crumbled by spring 1943 and were forced to surrender.

- Adrian Gilber, Germany's lightning war from the invasion of Poland to El Alamein, Amber Books, Osceola, 2000