Tunisian Campaign

The Allies defeat the Axis in North Africa

17 November 1942 - 9 May 1943

The Tunisian Campaign consisted of a series of battles which took place in Tunisia between the Axis and Allied Forces of World War Two. Although initially the Germans and Italians had some success, the Axis’ supply problems led to defeat. In the end over 230,000 Italian and German soldiers were taken prisoners.

1 of 4

When they landed in Africa, as the American historian Rick Atkinson states, the soldiers of the US Army ‘were fine men, but not yet a good army’. To defeat the Germans in northwestern France they would need to be both. The campaign in North Africa proved the best possible training ground for this.

2 of 4

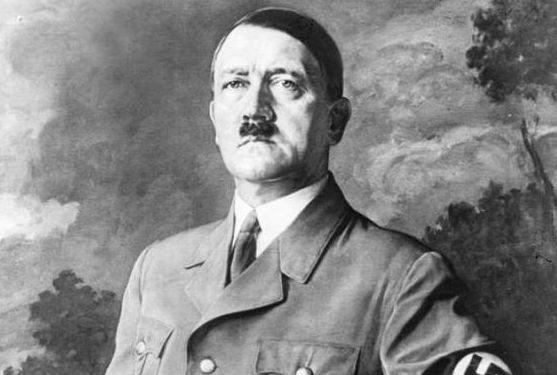

Adolf Hitler’s decision to continue to pour reinforcements into North Africa meant that the number of Axis troops captured was far higher than if he had ordered a withdrawal to Sicily immediately after Operation Torch. Hitler actually sent far more men into Africa after Torch than the Germans had commanded in their initial struggle against the British in Libya and Egypt.

3 of 4

Whatever setbacks they suffered, the tide of war in North Africa was running overwhelmingly in the Allies’ favor. The caution of the Italian High Command denied German General Erwin Rommel a chance to exploit a brief opportunity to outflank and destroy Allied forces in northern Tunisia. The Americans were reinforcing rapidly, while German strength was shrinking.

4 of 4

After the Germans’ epic defeat at Stalingrad and expulsion from North Africa, there was no doubt among the Allied nations about the outcome of the war. Yet, if the tide was now running strongly for the Allies, great uncertainties persisted about the course and duration of the war. While Churchill ordered the church bells of Britain rung for victory in North Africa, much more pain and hardship lay ahead before the Allies would enjoy real cause for celebration.

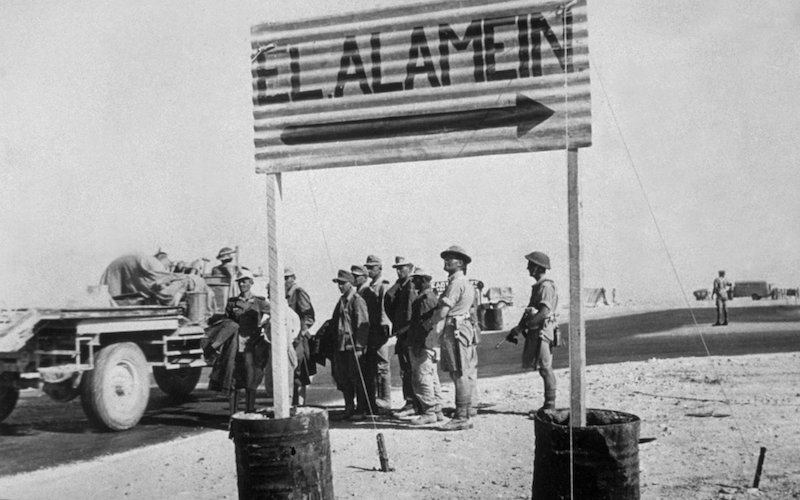

For the first two years of conflict in North Africa, the British on one side, and the Germans and Italians on the other, battled for control of Egypt and Libya. The defeat at El Alamein forced the Axis forces to retreat into a trek through Libya and into Tunisia, with the British in pursuit. At the same time, in November 1942, came Operation Torch, an Anglo-American invasion of French Algeria and Morocco. After the success of this operation the Axis forces found themselves pressed in Tunisia from the east and west.

1 of 5

General Bernard Montgomery’s relatively tardy and cautious follow-up to the victory at El Alamein – he took nine days to retake Tobruk – has been much criticized, but he did not want to overreach himself, especially against an adversary like General Erwin Rommel. Heavy rain at Fuka ended the 2nd New Zealand Division’s hopes of cutting off the Afrika Korps’ long retreat back to Tripoli. ‘Only the rain on 6 and 7 November saved them from complete annihilation,’ wrote Montgomery afterwards. ‘Four crack German divisions and eight Italian divisions had ceased to exist as effective fighting formations.’ ‘The doom of the Axis forces in Africa was certain,’ he wrote later, ‘provided we made no mistakes.’

2 of 5

In the course of December 1942, the Germans turned and fought several fierce rearguard actions, but on each occasion Eighth Army prised them from their positions and pushed on. Tripoli fell on 23 January 1943. Three days later, Montgomery’s forces found themselves in Tunisia, where the last protracted phase of the North African war was fought out.

3 of 5

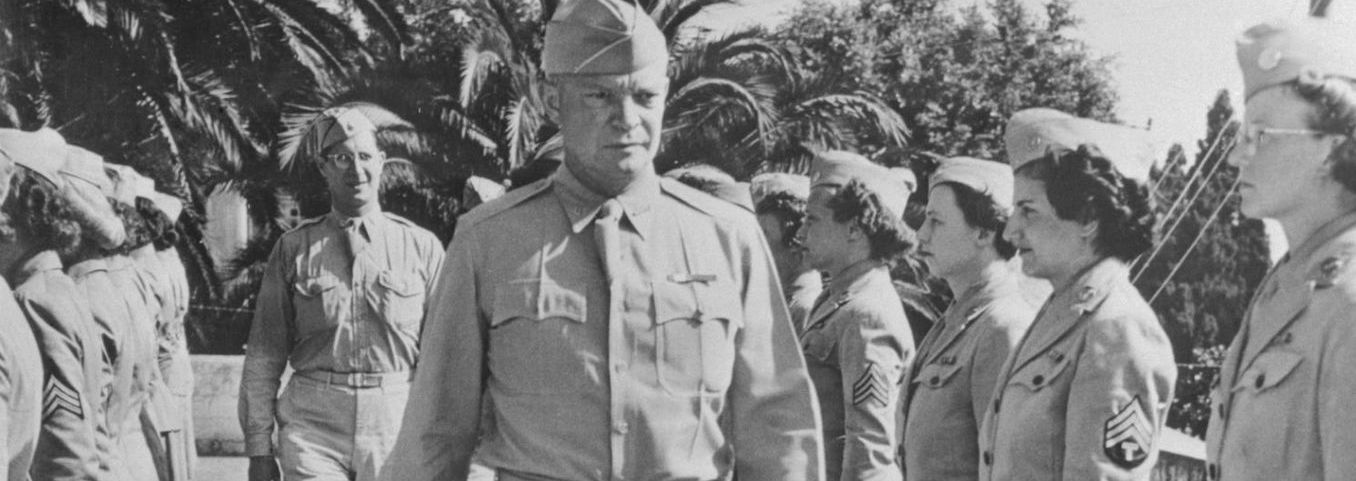

Montgomery’s victory at El Alamein should have provided a powerful inducement for the Vichy authorities in Africa to cooperate with the Allies during the invasions of Morocco and Algeria, codenamed Operation Torch. The fighting nonetheless cost the French 3,000 casualties over three days, and the Allies 2,225. Small wonder that Torch’s commander, the American general Dwight D. Eisenhower, wrote: ‘I find myself getting absolutely furious with these Frogs.’

4 of 5

Operation Torch was undertaken because the British refused to re-enter the European continent in northwest France – where they had been ignominiously expelled in June 1940 – until the Wehrmacht had been significantly weakened on the Eastern Front by the Russians, Germany had been heavily bombed, the Middle East was safe and the battle of the Atlantic unequivocally won.

5 of 5

General George C. Marshall’s April 1942 plans for an early return to France – with either a nine-division assault codenamed

Sledgehammer, or a forty-eight-division invasion codenamed Roundup – were both judged far too risky by General Alan Brooke, the chairman of the British Chiefs of Staff as well as Chief of the Imperial General Staff. ‘The plans are fraught with the gravest dangers,’ he confided to his diary. ‘The prospects of success are small and dependent on a mass of unknowns, whilst the chances of disaster are great and dependent on a mass of well established military facts.’

Western Desert Campaign until the Fall of Tobruk

The campaign in North Africa’s Western Desert began with the Italian invasion of Egypt, a British protectorate at the time. Afterwards the British launched Operation Compass and italian dictator Benito Mussolini sought help from his German allies.

Battles of El Alamein

El Alamein was a decisive victory in the African campaign for the Allies. Winston Churchill affirmed: “We can almost say that before Alamein, we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat”.

Operation Torch

Operation Torch was the name given to the Allied invasion of French North Africa . Operation Torch was the first time the British and Americans had jointly worked on an invasion plan together.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011