Siege of Antwerp

German army captures the city of Antwerp

28 September - 10 October 1914

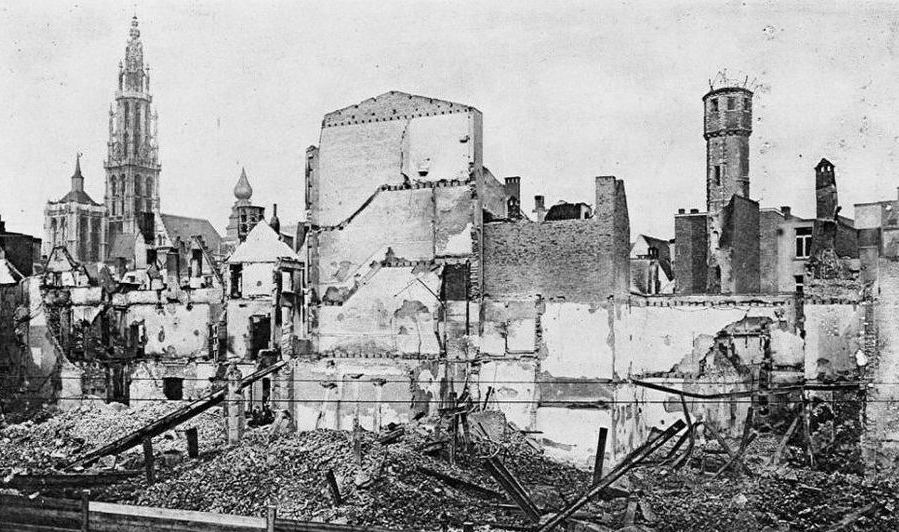

The Siege of Antwerp was a battle fought on the Western Front of World War I between the German Imperial Army and the Entente forces of Great Britain and Belgium. The Germans besieged the Belgian army and the British Royal Naval Division in the Antwerp area, after the German invasion of Belgium. With no hope of holding Antwerp, the Belgian army withdrew towards the Yser river. In the Battle of the Yser, close to the French border, the Belgians held out against the German onslaught and defended the last part of unoccupied Belgium. The Belgians held the area until late 1918, when they participated in the liberation of Belgium.

1 of 6

Antwerp was the most heavily defended of the three fortified Belgian complexes of 1914, and it had the most modern forts: twelve of its nineteen forts had been built between 1907 and 1910, and one of the forts, Bornheim, dated from September 1913.

2 of 6

Antwerp, like Verdun, had numerous small structures — called, variously, fortins or ouvrages — scattered in the intervals between the forts. Antwerp, like Namur and Liège, was heavily gunned.

3 of 6

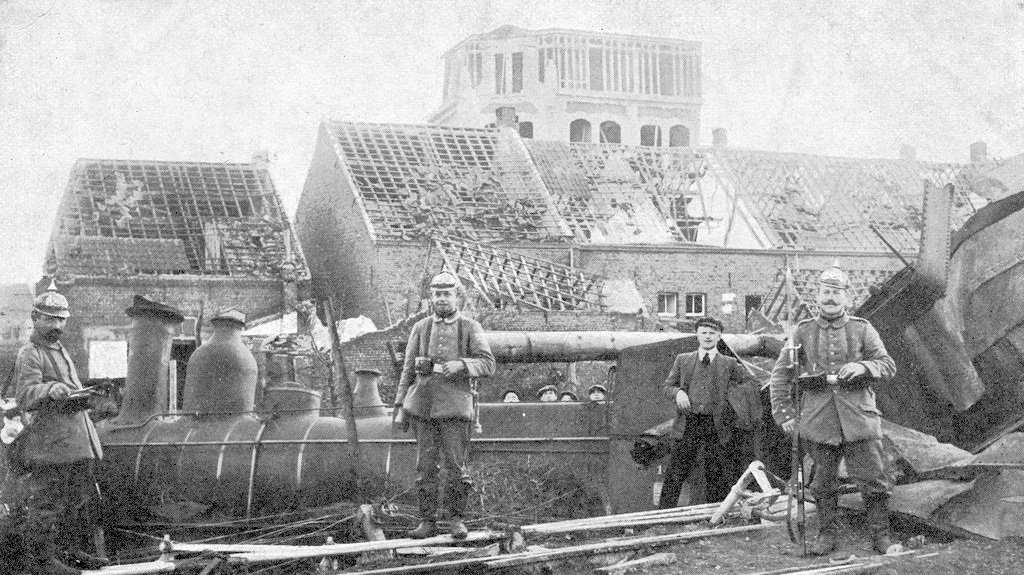

As might be expected from troops with little experience, the Germans made all sorts of costly mistakes. They didn’t manage to seal off the perimeter of Antwerp sufficiently, so reinforcements went in and, as the siege came to its inevitable conclusion, most of the Belgian Army was able to slip out.

4 of 6

Once the Race to the Sea gathered speed, the Germans knew that they must eventually deal with the problem posed by Antwerp, to which the Belgian Field Army had withdrawn.

5 of 6

The eleventh-hour British contribution to Antwerp's defence was too small to save the city; however, it did help to delay the surrender for some five days, winning precious time for the main British Expeditionary Force to reach Flanders.

6 of 6

As the fighting developed along the coast, and specifically on the Yser, the guns of Germany's battleships could have made a significant tactical contribution. But the fleet — partly out of ignorance as to the Grand Fleet's position as well as of its own army's situation — did not push its cause, and General Erich Falkenhayn did not ask for its aid.

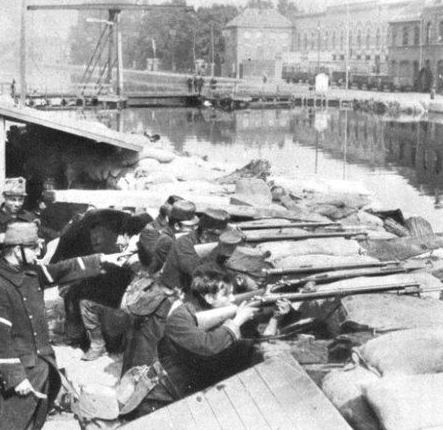

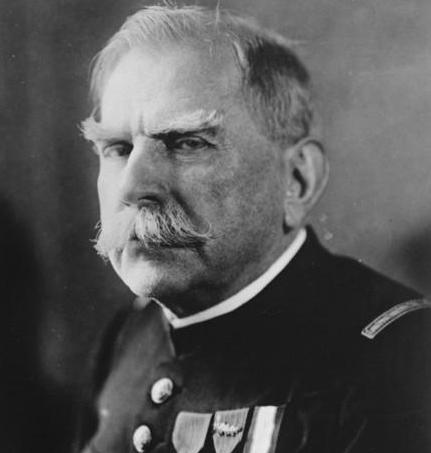

By this point, what was left of the Belgian army was at Antwerp: a force of six divisions and eighty-seven battalions of artillery. This was much more than a garrison: it was a force large enough to make the threat of Antwerp as a port quite real. The Belgians conducted three separate offensive operations out of Antwerp. And, as the siege progressed, Antwerp received reinforcements: British marines and French naval troops. General Hans von Beseler, who had the task of taking Antwerp, had only been given about eighty-five thousand men to do it with. Not only was he outnumbered, but his forces were hardly first-line troops.

1 of 5

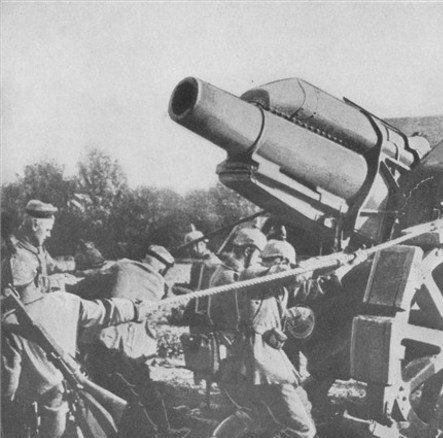

Von Beseler had the Third Reserve Corps, which contained six reserve infantry regiments and two regiments of Landwehr, the so-called Marine Division, which consisted of sailors, three independent brigades of Landwehr, and the fourth Ersatz division, which consisted of three mixed brigades. Von Beseler didn’t have much in the way of soldiers, but he had an enormous deployment of firepower. The Naval Division alone had three batteries of 305 mm howitzers, one battery of 210 mm howitzers, one battery of 150 mm howitzers, and three batteries of 100 mm guns. In addition, von Beseler had two of the monster 420 mm guns, as well as four Austrian and two German 305 mm howitzers. He also had engineer units equipped with heavy mortars, as well as ordinary field artillery.

2 of 5

The Belgians had learned something from their defeats. When General Gerard Leman had pulled out his infantry from Liège, he had given the German artillery observers a free ride. Now the Belgians realized their error. To have any chance of success, the defense of a fortified place required a joint effort involving the garrisons of the forts, infantry operating in the intervals between the forts, and artillery behind the forts. Besides, Antwerp was the last defensible Belgian position. So the army stayed put and von Beseler’s troops had to attack each position separately.

3 of 5

Ersatz divisions were composed of men who had not been called up for compulsory military service before the war owing to the budget restrictions placed on the army by the Reichstag. Since they had done no military service prior to the war, they had to be put into newly formed units and given their basic training. By the time the siege started, these men had perhaps two months of military experience. At the other end of the spectrum, the Landwehr consisted of men whose basic training had been decades earlier.

4 of 5

The Belgian perimeter was 96 kilometres in length, but its main defences were concentrated in an outer ring. These provided concentrated targets for the German artillery attack. A dispersed defence, less reliant on armor and concrete, would have stretched the Germans' heavy artillery and ammunition supply to far greater effect.

5 of 5

The Belgian general staff, whose chief was responsible for the army when it was in the field, favored operations that were independent of the city. This line of thought tied in with the hopes of the French mission, who wished to see the Belgian army cooperating in the French great allied envelopment developing from the south, planned by General Joseph Joffre. But while the field army was within the fortifications, its command was in the hands of Antwerp's governor. His need was to pull the British and French to the Belgians, rather than to have the Belgians pulled to the British and French.

First Battle of the Marne

During the First Battle of the Marne the Entente forces obtained a decisive defensive victory against the German Army. By organizing a successful counter attack the Entente managed to stop the Germans' advance towards Paris and stabilize the front.

First Battle of Ypres

During the First Battle of Ypres the German Empire attempted to attack the Entente forces on a wide front in a attempt to, at last, secure victory in 1914. However, by the time of the attack the British, French and Belgian armies managed to solidify their defensive positions. The Germans could not break through and now faced the very thing which they sough to avoid: a prolonged war on two fronts.

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003