First Battle of the Marne

Entente forces counter attack

5 - 12 September 1914

The First Battle of the Marne was fought on the Western Front of World War One between the German and Entente forces. The battle was the conclusion of the Battle of the Frontiers that put the Germans in pursuit of the retreating Franco-British armies. The Germans had reached the outskirts of Paris when a counterattack by the British Expeditionary Force and six French armies, along the Marne river, forced the Germans into retreat.

1 of 6

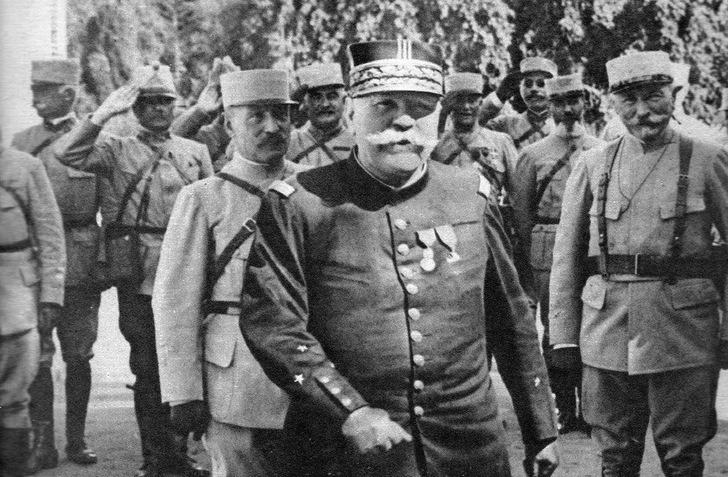

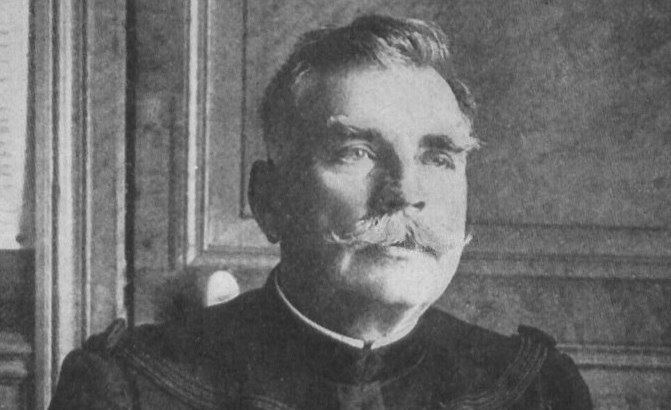

The First Battle of the Marne proved a stunning strategic triumph for the French. As might be expected there were many claimants for the laurels of victory, but there is no doubt who would have been blamed had it all gone wrong: the French Commander in Chief, General Joseph Joffre. Therefore, the greatest credit should go to him.

2 of 6

At times the Germans had seemed close to success, but the French armies had shown a resilience in defence that had thwarted any decisive breakthrough.

3 of 6

The 'Miracle of the Marne' saved Paris and dealt the final blow to German plans for a swift victory in the west. In many respects the Marne fighting had boiled down to a battle of wills between the opposing commanders. However, even though the Entente gained a momentous strategic success on the Marne, they were still a very long way from defeating the German armies.

4 of 6

If France were defeated by Germany, Britain would be left without a major striking force on the continent, and its hopes of neutralizing the Channel ports and Belgium would be dashed for the foreseeable future. Britain had already discovered that its need for security meant that it could not abandon the Entente in July; now the same imperative meant that it had to stick by it in the field. Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and his ministers decided to support the French counterattack.

5 of 6

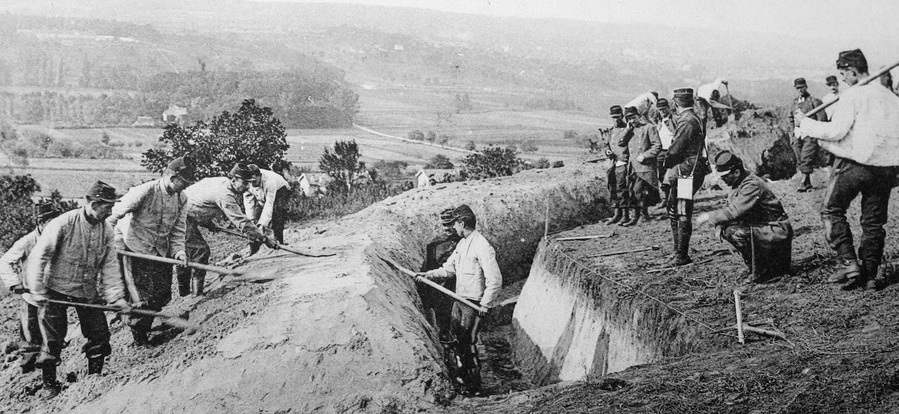

The Aisne is a deep, wide river, passable only by bridge. At the outset of the battle there, not all the existing bridges had been destroyed, while others were improvised; none of the bridges were safe while within range of German artillery fire. The high ranking British and French commanders had recognized the need for energetic and rapid pursuit, seeking objectives beyond the Chemin des Dames, the road running along the northern ridge of the Aisne valley. But their subordinate commanders were more cautious.

6 of 6

With deadlock gripping the front from the Aisne eastwards, each side tried to turn the other's open flank to the west and north in what became known as the 'race to the sea'.

With disaster looming everywhere up and down the front, the attention of the Entente countries now fell on the figure of French General Joseph Joffre. The Germans were seeking absolute victory prior to turning their attentions to the Russian Army. Joffre knew that his armies were hurting, but he was also convinced that France was not yet beaten. The French Army was so huge that a knockout blow was extremely difficult for the Germans to deliver. Joffre also began to consider his tactical options if he was to counter the onrushing march of the German right wing now wheeling through northern France.

1 of 6

‘GHQ at that time consisted of some fifty officers, counting those belonging to the Services (railways, subsistence, medical department, mail section, code section, motor-cars and headquarters commandant). The routine at GHQ, as established from the very start, continued unchanged throughout the war. There were two reports each day: the first called the Grand Report, was held in my office at 7 a.m; the second took place towards 8 p.m. At the Grand Report there were normally present the Chief of Staff, the Assistant Chiefs of Staff, the Director of the Rear, the Chiefs of Bureaux and the officers of my cabinet. At both the morning and evening meetings I was informed as to the contents of reports sent in from the various armies relating the events of the preceding twelve hours, together with all information gathered during that time concerning the enemy. Naturally, if important reports or despatches arrived during the course of the day or night they were immediately presented to me; but the principal interest attaching to the two daily reports consisted in what might be called ‘taking our bearings’. At the morning report the general situation was established. I frequently requested the officers present to express their personal opinions on the questions before us; after listening to what they had to say, I gave my decisions.’ (General Joseph Joffre)

2 of 6

An army of millions had an enormous capacity to absorb punishment. But the French needed sure leadership if they were not to fall apart at the seams. This, then, was Joffre’s moment. He had based his General Headquarters at Vitry-le-François, where early on he had established a routine that would continue through good times and bad. It may not have been exciting or dramatic but the decisions made at the regular meetings would at times decide the fate of nations.

3 of 6

In many ways Joffre could only progress from the moment he accepted that his original assessments of the situation had been utterly mistaken: the wrong tactics had been followed and, to some extent, the wrong men had been put in charge of operations. One understandable response might have been panic, but that was not Joffre’s style. Slowly, methodically, he began working his way through the mass of problems that flowed across his desk.

4 of 6

Joffre issued orders to correct the previous mistakes, but in the press of battle it was difficult to get a whole army to adjust its long-standing mentality and for new ideas to penetrate. However, there was something he could do about the generals he considered to have been found wanting in action: ‘When the test came, a large number of our generals had shown that they were not equal to their task. Amongst them were some who in time of peace had enjoyed the most brilliant reputation as professors; there were others who, during map exercises, had displayed a fine comprehension of maneuver; but now, in the presence of the enemy, these men appeared to be overwhelmed by the burden of their responsibility. In some of the larger units there had been a complete abdication of command.’

5 of 6

‘My own preference consisted in creating on the outer wing of the enemy a mass capable, in its turn, of enveloping his marching flank. If we were to have time to assemble in the region of Amiens a force large enough to produce a decisive effect against the marching flank of the enemy, it was necessary to accept a further retreat of our armies on the left. But we had reason to hope that by making good use of every obstacle by which the enemy’s advance might be retarded, and by delivering frequent counterattacks, these armies need not fall back farther than the general line of the Aisne, prolonged by the bluffs running from Craonne to Laon and La Fère. The Third Army would rest on the fortifications of Verdun, which would thus serve as a pivot for the general movement in retreat. The French Fourth and Fifth Armies, the British Army and the Amiens group, constituted with forces taken from our right wing, would furnish a mass capable of resuming the offensive at the moment the enemy, debouching from the wooded regions of the Ardennes, would have to fight with this difficult ground lying behind him. My conception was a battle stretching from Amiens to Rheims with the new army placed on the extreme left of our line, outside of the British and in a position to outflank the German right.’ (General Joseph Joffre)

6 of 6

This might be Joffre’s last opportunity to avoid disaster. Timing would be all-important. In the meantime the Fifth Army and the BEF would continue to fall back, with the Third Army acting as the pivoting point, anchoring the two retreating armies to the rest of the French line. Military orthodoxy in 1914 regarded redeployment by rail during the course of operations as excessively dangerous. Troops in trains were necessarily out of the fighting line. But Joffre's own experience with railways, and the fact that he had already — before the war — studied the possibility of just the operation which he now proposed, encouraged him to try it.

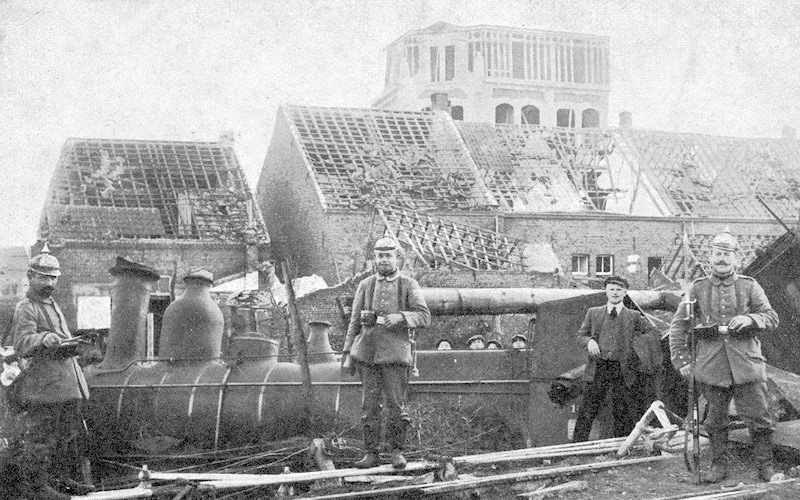

Siege of Antwerp

During the siege of Antwerp the Germans, with a small force, managed to capture the city of Antwerp and its surrounding garrison from the Belgian Army. After the siege the Belgians fell back to the Yser river.

First Battle of Ypres

During the First Battle of Ypres the German Empire attempted to attack the Entente forces on a wide front in a attempt to, at last, secure victory in 1914. However, by the time of the attack the British, French and Belgian armies managed to solidify their defensive positions. The Germans could not break through and now faced the very thing which they sough to avoid: a prolonged war on two fronts.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998