Operation Alberich

German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line

9 February - 20 March 1917

Operation Alberich was a German operation on the Western Front of World War I. It was a planned withdrawal to the shorter and thus more easily defensible Hindenburg Line. The withdrawal eliminated two salients which had been formed in 1916 during the battle of the Somme, between Arras and Saint Quentin and from Saint Quentin to Norron.

1 of 2

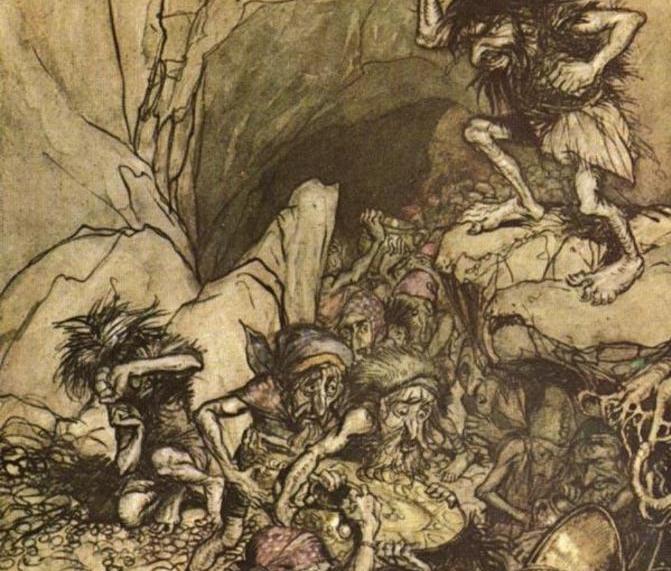

The scheme for the rearward movement was code-named Alberich, after the malicious dwarf of the Nibelung Saga. This was appropriate since the withdrawal was accompanied by a 'scorched earth' policy. Through the whole of the area being abandoned, the Germans felled trees, blew up railways and roads, polluted wells, razed towns and villages to the ground and planted countless mines and booby-traps. While children, mothers and the elderly were left behind with minimal rations, over 125,000 able-bodied French civilians were transported to work elsewhere in the German-occupied zone.

2 of 2

The British and French approached the new year with a considerable degree of confidence. The Entente leaders had no idea that revolution would first cripple and then remove their Russian ally from the war. All they knew was that the Somme and Verdun campaigns had been horrendous experiences for the German Army, while the Russian Brusilov Offensive had put it under additional pressure on the Eastern Front. There was a hope – a conviction, even – that the German Army must be approaching exhaustion.

The chief effect of two years of bombardment and trench-to-trench fighting across No Man's Land was the creation of a zone of devastation of immense length – more than 400 miles between the North Sea and Switzerland – but of narrow depth: defoliation for a mile or two on each side of No Man's Land, heavy destruction of buildings for a mile or two more, and scattered demolition beyond that.

1 of 4

At Verdun, on the Somme and in the Ypres salient, whole villages had disappeared, leaving a smear of brick-dust or piles of stones on the upturned soil. Ypres and Albert, sizeable small towns, were in ruins; Arras and Noyon badly damaged; the city of Rheims had suffered heavy destruction and so had villages up and down the line. Beyond the range of the heavy artillery, 10,000 yards at most, town and countryside lay untouched.

2 of 4

In the zone of German occupation, the military government ran an austere economic regime, driving the coal mines, cloth mills and iron works at full speed, requisitioning labor for land and industry and commandeering agricultural produce for export to the Reich. For the women of the north, desperate for news of husbands and sons away at the war on the wrong side of the line, managing by themselves, the war brought hard years.

3 of 4

The transition from normality to the place of death was abrupt, all the more so because prosperity reigned in the ‘rear area’; the armies had brought money, and shops, cafes and restaurants flourished, at least on the Entente side of the line.

4 of 4

In the French ‘Zone of the Armies’, a war economy boomed. Outside the ribbon of destruction, the roads were full of traffic, long lines of horse and motor transport going to and fro, and in the fields, ploughed by farmers right up to the line where shells fell, new towns of tents and hutments had sprung up to accommodate the millions who went up and down, almost as if on factory shifts, to the trenches.

Nivelle Offensive

The Nivelle offensive was a Franco-British plan on the Western Front of World War One. Designed by its architect, General Robert Nivelle, to be strategically decisive, the offensive failed to force a decisive battle with the German forces.

Flanders Offensive

During the Flanders offensive a battle for control of the ridges south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres took place. Although the Entente forces managed to gain some initial ground they failed to force a German general retreat.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998