Nivelle Offensive

Failed Franco-British offensive

16 April - 9 May 1917

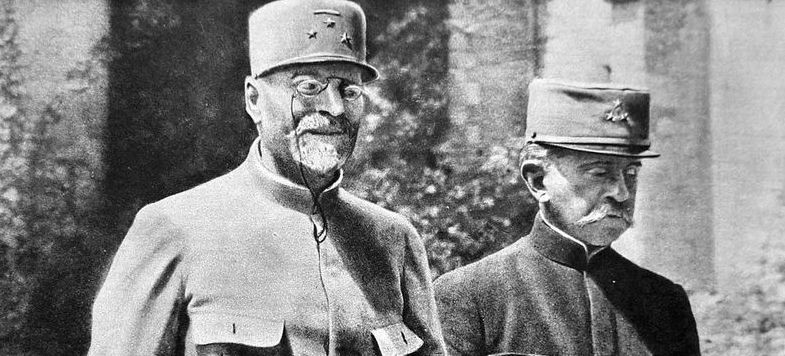

The Nivelle offensive was conducted by French and British forces on the Western Front of World War 1. The French intended for the offensive to be decisive by breaking through the German defences in the Aisne area within 48 hours. Although the offensive was tactically successful, with the French and British forces capturing territory previously occupied by the Germans, the Entente forces did not manage to achieve their primary strategic objective: the attempt to force a decisive battle on the Germans failed. The failed offensive led to mutinies in some units of the French Army and the dismissal of Robert Nivelle as the Chief of the General Staff.

1 of 6

Measured against the terrible yardstick of Verdun, the total casualties for the whole offensive were not overwhelmingly high.

Nevertheless, because Nivelle had promised so much, the shock of disappointment felt by the French Army and people when the

breakthrough failed to materialize was all the more severe. As a wave of unrest and indiscipline engulfed the French Army, Nivelle was dismissed from the post of Commander-in-Chief.

2 of 6

The Anglo-French plan for the spring of 1917 was unravelling at two levels. First, the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg line had upset its operational assumptions: the left wing of the French offensive on the Aisne now had no opponent. Second, it would not be part of a coordinated assault on Germany’s central position.

3 of 6

The Nivelle offensive was barely under way when the French Army began to experience its worst internal crisis of the war. That day, 17 soldiers of the 108th Infantry Regiment left their posts in the face of the enemy. This was the first in a series of acts of collective indiscipline which, after reaching a peak in June, continued into the autumn. Sixty-eight out of 112 French divisions were affected by the wave of mutinies.

4 of 6

Mutinies began in late April, grew in May, and peaked in June. Concentrated in the sector from Soissons to Reims, many of them involved units which refused to return to the line, having had too little opportunity to recover and rebuild. They can be characterized as soldiers’ strikes: reactions to bad command, inadequate officers and poor conditions of service. The French army, it seemed, was still ready to defend France, but on its own terms.

5 of 6

The British launched their attack round Arras, at the northern extremity of what would have been the German salient. Its role was strictly limited: to pull German reserves away from the River Aisne. Well planned and well executed, it revealed that the learning curve on which the army had embarked in 1915 was now bearing fruit. Restricted to a front of 24 km, the battle was fought as a series of limited and staged attacks, leapfrogging each other, and with pauses to consolidate after each.

6 of 6

A great offensive had been planned for 1917 at the meeting of Entente military representatives at Chantilly, French general headquarters, in November 1916. This meeting was a repetition of the Chantilly conference of the previous December which had led to the battle of the Somme and to the Brusilov offensive.

Nivelle was confident that the tactics he had used at Verdun would bring him success on a larger scale. There he had relied on narrow front attacks in which the artillery created a narrow corridor through which the infantry could push forward. Now, at last, he believed the French had enough heavy, long-range guns to attack on a wide front, allowing a single, crunching thrust to be made by the French Fifth and Sixth Armies. The heavy artillery would then be moved forward as quickly as possible to maintain the momentum, forcing a complete breakthrough by the Tenth Army.

1 of 5

One key feature of the offensive was to be surprise; but surprise proved impossible. Nivelle was himself less than discreet in discussing his plans in front of civilians, and security was further compromised by an assortment of French deserters.

2 of 5

Nivelle's preparations had been plagued by problems. Aristide Briand's government fell and the new French Prime Minister, Alexandre Ribot, entrusted the Ministry of War to Paul Painlevé, a Socialist with little faith in Nivelle's ideas. Painlevé’s military thinking was shaped by the defensively minded Pétain, who in turn was unconvinced by Nivelle.

3 of 5

The German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line largely nullified the French Northern Army Group's planned contribution to the offensive. The German retirement did have some benefits for the French since it enabled the Northern Army Group to release 13 divisions and 550 heavy artillery pieces for use elsewhere. It also gave the French the opportunity to assault the flank of the German position north of the Aisne and to direct an enfilade of artillery fire against the western portion of the defences on the Chemin des Dames ridge.

4 of 5

To add to Nivelle's troubles, Joseph Alfred Micheler – whose Army Group was expected to achieve and exploit the breakthrough on the Aisne – had serious misgivings about the coming offensive. In a letter to Nivelle, Micheler pointed out that the Germans too had extra reserves available as a result of their withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line. Consequently it might no longer prove possible for the Reserve Army Group to effect a breakthrough as quickly as Nivelle required. Although Micheler's anxieties were shared by the other Army Group commanders, Nivelle would not make any fundamental amendments to his overall plan or chosen tactics.

5 of 5

As a result of the German evacuation of Artois, Nivelle’s front had moved to his right, and he was now attacking out of a cul-de-sac, going from south to north, towards the River Oise. Few roads and railways ran in that direction. The towns on the south bank of the Aisne were too small for the infrastructure now required of them. On the north bank the intersected slopes rose steeply to the ridge, along which ran the Chemin des Dames.

Operation Alberich

Operation Alberich was a German planned withdrawal that took place in France on more easily defensible positions.

Flanders Offensive

During the Flanders offensive a battle for control of the ridges south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres took place. Although the Entente forces managed to gain some initial ground they failed to force a German general retreat.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003