Warsaw Uprising

Polish Resistance organises an uprising against German occupation

1 August - 2 October 1944

On this day there was an important meeting in Warsaw during which Colonel Janusz ‘Sek’ Bokszczanin reported the Soviet’s intentions in not aiding the uprising. Also present at the meeting was notable resistance fighter Jan Nowak, who had just returned from London. He gave several vital pieces of information to Bór-Komorowski: Generał Sosnkowski was against an uprising; the AK could not count on support from outside Poland because both the Polish Parachute Brigade and the Polish Air Force were now under Allied command; and the Polish squadron in Italy was very small.

1 of 3

Bokszczanin reported: “Soviet artillery fire is so far only intermittent and light. It does not seem to be an artillery preparation for a general forced crossing of the Vistula and an attack on the city. The armoured reserves which the Germans are directing to the front near Warsaw are fully equipped and prove that they intend to fight at the bridgehead. Until the Soviet army shows clear intention of attacking the city, we should not start operations. The appearance of some Soviet detachments on the outskirts of Praga does not signify

anything. They may simply be reconnaissance patrols.”

2 of 3

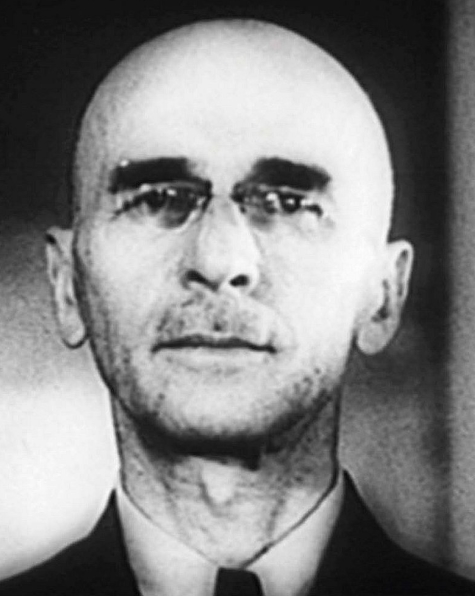

It was clear that opinion on calling an uprising was split. Crucially the man who was to command the Warsaw Uprising, General Antoni ‘Monter’ Chruściel, was against launching it, because of the lack of arms in the city for his troops, as was the AK head of intelligence, Colonel Kazimierz ‘Heller’ Iranek-Osmecki. Opposing him was Generał Leopold ‘Kobra’ or ‘Niedźwiadek’ Okulicki, who had been a prisoner of the NKVD in 1941, had been released and had returned to Poland by parachute. His hatred for the Soviets knew no bounds and he was willing to take any risks in the cause of Polish independence.

3 of 3

Bór-Komorowski and Jankowski decided that the uprising would start soon but would only last for 3–5 days. General Antoni ‘Monter’ Chruściel told the meeting of the AK command that he had received information that Soviet tanks were entering Praga, Warsaw’s eastern suburb on the banks of the Vistula. This news electrified the meeting and so the die was cast: the uprising would begin.

As the Red Army approached Warsaw and soon after crossed the Vistula south of the city, the Polish Prime Minister, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk flew to Moscow to confer with Stalin. Expecting to overrun the Polish capital quickly, Soviet radio called on the public in the city to rise against the Germans as the thunder of artillery could be heard from the nearby front.

1 of 7

In the original plans for Operation Burza, no role had been assigned to Warsaw, therefore the question has to be asked: why did the Warsaw Uprising take place? The government delegate, Jan Jankowski, gave what is probably the best analysis: “There were several reasons for our uprising. We wanted to repel by force of arms the last blow the Germans were preparing to deal at the moment of their departure to all that was still living in Poland; we wanted to thwart them in their aim of revenge on insurgent Warsaw. We wanted to show the world that although we wanted to have an independent Poland, we were not prepared to accept this gift of freedom from anyone if it meant accepting conditions contrary to the interests, traditions and dignity of our nation. Finally, we wanted to free Poland from the nightmare of the Gestapo punishments, murder and prisons. We wanted to be free and to owe this freedom to nobody but ourselves.”

2 of 7

The AK commanders were acutely aware of the threat of the communists. The communist radio station Kościuszko was making broadcasts calling on the population of Warsaw to rise up and liberate themselves, and leaflets appeared in Warsaw containing a call to battle addressed to the AL, the communist resistance, and issued in the name of Molotov and Polish communist leader Edward Osóbka-Morawski. The radio broadcasts were picked up by the radio monitoring stations in Britain.

3 of 7

Given permission to act when ready by Mikolajczyk, the Polish commander in the city, General Antoni ‘Monter’ Chruściel, ordered an uprising. He and his men could sit it out and be condemned as useless or pro-German—the latter a favorite term of condemnation applied to them by the Soviet government—or take a chance on either winning control of the city at least temporarily or going down to defeat.

4 of 7

The members of the AK wore a red-and white armband but few had more formal uniforms. Most wore a mixture of old Polish uniforms, British uniforms, and about 3,000 German uniforms stolen from a warehouse. The use of the latter caused confusion when the AK

encountered the Soviets and led to allegations that the AK were on the German side.

5 of 7

Secret food caches had been created in five locations throughout the city, containing 90,000 rations. In the event all five were in areas that the AK never controlled, and so the population of the city suffered greatly from hunger during the uprising. Indeed, food supplies

were particularly low as the retreating German armies had taken everything with them.

6 of 7

The AK were strengthened by cooperation with other armed units. The AL, which had about 400 men in the city, put itself operationally

under AK command but fought separately; it was woefully under armed. About 1,000 Jewish survivors also took part: one ŻOB platoon joined the AL while another joined the AK. Various other nationalities present in Warsaw helped: Italians who had deserted the Germans, escaped Soviet POWs, Hungarians, Slovaks and a Frenchman. An escaped British POW, John Ward, had joined the AK and during the uprising would telegraph reports to London. He was invited to submit daily bulletins on the fighting to The Times.

7 of 7

The next two months saw something like a repeat performance of the 1939 invasion against Poland. The Red Army had slowed down

on the approaches to Warsaw. Now it halted short of the Vistula—pushing to the river only after the insurgents had been driven away from the opposite bank—and placed its emphasis on expanding bridgeheads over the river south of Warsaw and obtaining bridgeheads across the Narev river to the north.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Kenneth K. Koskodan, No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in World War Two, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2009

- Halik Kochanski, The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2012