Spring Offensive

Germany's last gamble for victory

21 March - 12 July 1918

The 1918 Spring Offensive, also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of attacks made by the German Army on the Western Front of the First World War. The offensive was designed by the Germans to overwhelm the Entente before the overpowering material and human resources of the United States could be fully deployed. In the end, the German offensive stalled, and the Entente began their own offensive operation, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, which would ultimately lead to a German retreat, the collapse of the Hindenburg Line and the end of the war.

1 of 4

During the offensive, the Germans had superiority in numbers for the first time on the Western Front, because they were able to redirect troops from the East after the defeat of the Russians. There were four offensives and no clear objective was established for them: the targets of the attacks were changed according to battlefield conditions.

2 of 4

Planning at the operational level in the winter of 1917-18 was as confused as that of overall strategy. If the aim was to knock out France, Verdun was still the sector that could be treated in isolation. But the battle of 1916 carried its own lesson: the French army would not easily give in. The British army was seen as a softer nut; less adroit and less committed to holding ground which was not its own.

3 of 4

A major retraining program was instituted during the winter in an attempt to acquaint more units with the tactics developed by the elite assault units, or storm troops, over the previous two years. Approximately one quarter of German infantry divisions were designated 'attack divisions' and received the best new equipment and weapons, including light machine-guns. The remainder, primarily responsible for holding the line, were classified as 'trench divisions'.

4 of 4

With their formations not only weakened by recent battles and reorganization but also containing large numbers of raw conscripts, the British were hardly in an ideal condition to resist the approaching German onslaught.

The overall situation in the war had not really changed: Germany was still likely to lose, but the Bolshevik Revolution and collapse of Russia had given her just a small window of opportunity in which she might possibly wrest victory from the clutches of defeat. Numerically the situation had never been more promising for the Germans, but the American forces were gathering and casting a long shadow across German plans. For the Germans, time was of the essence: whatever they were going to do would have to be done quickly. They had six months in which to change the course of the war.

1 of 4

The Russians had fought hard, but now they were finished, torn apart internally by competing visions of society and about to enter a nightmare that would envelop the country for decades.

2 of 4

The collapse of the Eastern Front freed the German High Command from the two-front conundrum that had racked it during the previous years. By the spring of 1918 when the German divisions had transferred from the Eastern Front to the Western Front, they were able to deploy some 192 divisions opposing only 156 Entente divisions.

3 of 4

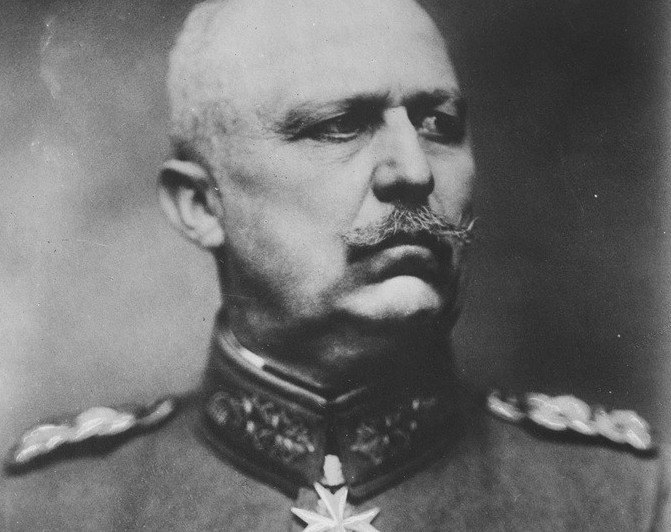

The Germans were certainly nervously awaiting the American arrival: ‘I felt obliged to count on the new American formations beginning to arrive in the spring of 1918. In what numbers they would appear could not be foreseen; but it might be taken as certain that they would balance the loss of Russia; further, the relative strengths would be more in our favor in the spring than in the late summer and autumn, unless, indeed, we had by then gained a great victory.’ (Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff, General Headquarters)

4 of 4

There was a distinct possibility that the German effort would dissipate itself in divergent directions. Germany had sufficient resources for one major offensive, but seemed to be committing itself to a series of indecisive engagements.

Battle of Cambrai

During the Battle of Cambrai the British forces attacked German positions with a large number of tanks. After the initial attack a German counter attack soon followed. By the end gains and losses on both sides were largely equal to one another.

Second Battle of the Marne

During the Second Battle of the Marne the German Army made one last attempt at a strategically decisive victory against the Entente forces. The initial German assault was repelled and the Germans suffered heavy casualties. A combined French-American counterattack forced a German retreat of some 28 miles. The battle, a decisive Entente victory, marked the beginning of the end for the German Army in World War One.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003