Battle of Cambrai

First major tank battle of the war

20 November - 6 December 1917

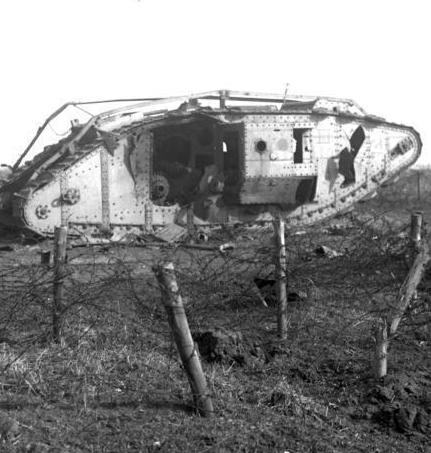

The Battle of Cambrai was fought between the British and German forces on the Western Front of World War I. It consisted of a British attack, followed by an immediate German counterattack, the largest one on the Western Front since 1914. Cambrai, an important supply point for the German Hindenburg Line, was attacked with a combination of artillery and tanks which were meant to raid the enemy positions. After an initial success on the first day, the weaknesses of the tanks made progress slow to a crawl. The rapid mobilization and efficient counter-stroke gave the Germans hope that they could achieve victory before American mobilization could overwhelm them.

1 of 5

Although its morale and manpower were stretched almost to breaking point by the fighting at Ypres, the British Expeditionary Force nevertheless made one more offensive effort in 1917. At Cambrai, the British concentrated their tanks so that, for the first time, they were deployed for a mass attack rather than being scattered in small groups along the front for local infantry support.

2 of 5

There remained one means of offence against the Germans that the mud of Flanders had until now made impossible: machine warfare. The main reserve of the Tank Corps, built up incrementally during 1917, had therefore remained intact. Its commander, Brigadier General H. Elles, had been seeking an opportunity to use it in a profitable way during the summer and had interested General Sir Julian Byng, commander of the Third Army, in the idea of making a surprise attack with tanks on his front, which ran across dry, chalky ground in which tanks would not be bogged down.

3 of 5

The assault at Cambrai evolved from a Tank Corps plan for a large-scale raid, the chief object of which was not to seize ground but to deal the Germans a bruising blow on terrain which, unlike the Ypres Salient, actually suited tanks. The Third Army staff expanded the scheme, transforming it into a major operation against the Hindenburg Line.

4 of 5

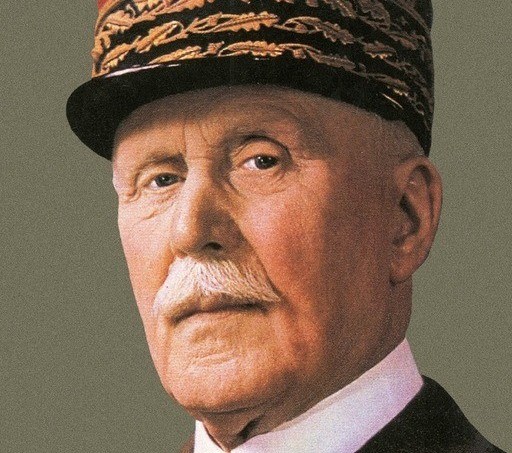

Since part of the Imperial General Staff’s misrepresentations to the War Cabinet involved suppressing the actual status of the French, who under Philippe Pétain had by now completed three offensive operations on the Western Front, it was hardly possible to mount a large joint operation without embarrassing questions being asked — or embarrassing comparisons being made, as after the Somme. The BEF now had a sizable tank force, and the ground around Cambrai was eminently suitable terrain as well.

5 of 5

Compared to the Somme and Third Ypres, where there had been no meaningful advance at all, Cambrai at first looked like a serious breakthrough. The offensive rolled right through the German lines and got to within a few kilometers of Cambrai. From that point on, Cambrai developed into the usual attack and counterattack tactics of the previous battles.

The underlying impetus for what became the Battle of Cambrai was provided by an artillery specialist called Brigadier General Hugh Tudor. He conceived a plan to capitalise on the vast improvements in artillery tactics and techniques, combined with the potential to use tanks, to reintroduce surprise attacks to the Western Front battlefields. The ultimate scheme was ambitious, embracing the capture of both the German First and Second Line Systems, the crossing of the St Quentin Canal, all followed by a cavalry advance to take the railway junction at Cambrai and the tactically significant Bourlon Ridge which glowered down on the whole sector.

1 of 5

Accurate surveying of the Western Front had been completed by 1917. This enabled a battery position and its target to be pinpointed on the map. This was then combined with the careful calibration of every gun to enable the gunners to make the correct adjustments to allow for defined error. All this meant that the artillery could suddenly open fire with a reasonable degree of accuracy. This ‘shooting off the map’, or predicted fire, could be done without previously registering the targets – something which had previously alerted the Germans to an imminent attack.

2 of 5

Tudor was unknowingly following a path of development similar to that of his German counterpart, Lieutenant Colonel Georg von Bruchmüller, who was engaged in similar experiments on the Eastern Front. The support of Douglas Haig, the BEF commander, was easily secured. He was not only in need of a morale-boosting success after the Third Ypres Offensive, but he also realised that the German forces would have been thinned out at Cambrai to reinforce the Ypres area.

3 of 5

The new artillery technique was then combined with the proven ability of tanks to flatten barbed wire, thereby avoiding the need for prolonged barrages to cut the wire for the infantry. This scheme and another idea for a 48-hour tank raid from the staff of the Tank Corps were swiftly welded together by the staff of the Third Army holding the Cambrai front.

4 of 5

Secrecy and speed would be all-important for the assaulting force of six infantry divisions, three tank brigades (476 tanks) and five cavalry divisions of the Cavalry Corps. After forty-eight hours the operations would be closed down if results were not satisfactory. There were no available reserves and this shortage of resources had been exacerbated by the despatch of two British divisions and heavy artillery batteries to the Italian Front.

5 of 5

Haig perceived advantages in a plan which might not only rebuild the BEF's reputation and revive morale but also simultaneously draw the enemy's gaze from the Italian Front, where the Italians had suffered a near-catastrophic defeat at Caporetto. The plan combined some promising tactical elements. These included the decision to abandon the customary long artillery preparation and to permit the supporting guns to deliver a surprise hurricane bombardment, capitalising on the new technique of 'predicted' shooting without prior registration of targets.

Spring Offensive

During the Spring offensive the German Army attempted to defeat the French and British armies before large scale American mobilization would alter the balance of the front. Although the offensive saw the Germans made the largest territorial advances since 1914, on both sides of the conflict, they could not force a decisive defeat on the Anglo-French forces.

Second Battle of the Marne

During the Second Battle of the Marne the German Army made one last attempt at a strategically decisive victory against the Entente forces. The initial German assault was repelled and the Germans suffered heavy casualties. A combined French-American counterattack forced a German retreat of some 28 miles. The battle, a decisive Entente victory, marked the beginning of the end for the German Army in World War One.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998