Road to power

At the moment of Napoleon Bonaparte’s entry onto the political stage in France, the situation in Europe was extremely complex, from political, economic and cultural standpoints. The French revolution of 1789 had wrought profound changes both in France and on the entire European continent. The Revolutionary Wars followed, an attempt made by the conservative forces to quell the ideas of the revolution. These created the right environment for young Napoleon Bonaparte’s drive, intelligence, charisma and ambition to propel him to the highest levels of power.

1 of 5

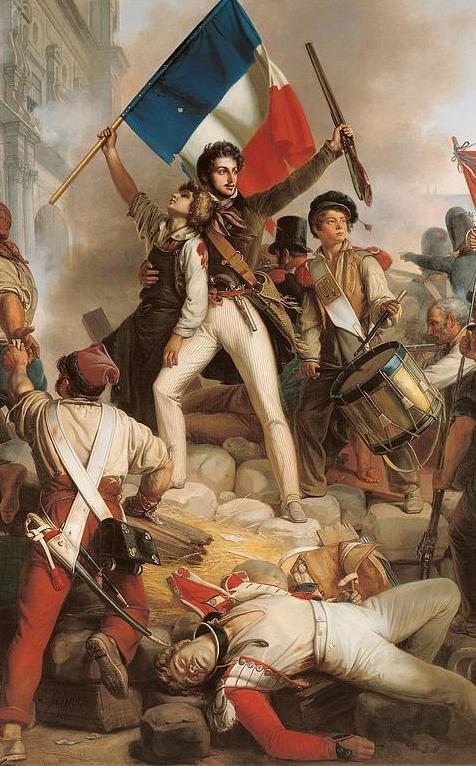

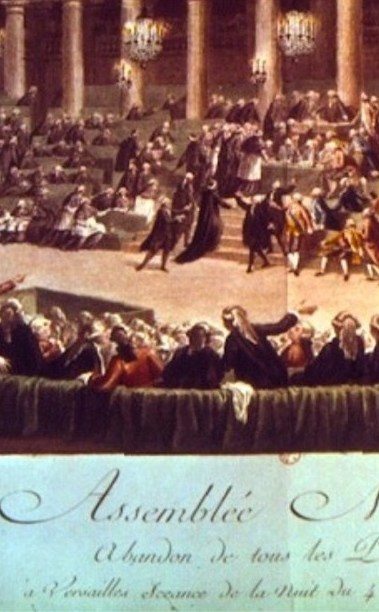

The French Revolution was one of the turning points in human history and happened rather as a long process than as an event. This process was a confrontation between political forces, representing, on the one hand, the social classes which felt oppressed, and on the other hand, the aristocracy, church hierarchy and the monarchy, all wanting to keep the status quo. This process continued to produce social, political and religious change almost ten years after it began, determining the following historical events: the creation of the First French Empire by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Napoleonic Wars.

2 of 5

Cultural and economic aspects also greatly affected the outworking of events at the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th. The beginnings of the industrial revolution ensured a capacity for mass production of different kinds of goods, including weapons, which contributed to the unprecedented magnitude of military conflicts. The ideas of certain enlightenment authors such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Alexis de Tocqueville and John Locke, who supported radical change in relationships between rulers and the masses, resonated with the aspirations of the oppressed social classes and contributed to the outbreak of the French revolution.

3 of 5

Thus, France was in a completely different position than that of the other European powers. Great Britain, the long-standing rival to French interests, was protected from the spread of revolutionary ideas, due mostly to the fact that it functioned as a constitutional monarchy. The ruling classes of other powers such as Prussia, the Habsburg Empire and Russia however, felt threatened by these changes and reacted by intervening directly in the French domestic conflict, on the side of the royalists. The French revolutionaries strengthened their forces, repelled foreign intervention and, under Napoleon’s leadership, went on the offensive in the so-called Revolutionary Wars.

4 of 5

The Napoleonic Wars which followed the Revolutionary Wars seemed to be more concerned with the fight for political and military supremacy on the European continent, than with the social-political battle of ideas started with the French Revolution. Under the leadership of Napoleon, France began to extend its influence over its neighboring countries, especially the Netherlands, Spain, Italy and the German States. At its climax, the French Empire controlled most of the European continent, imposing the Continental System which severed Europe’s ties with Great Britain.

5 of 5

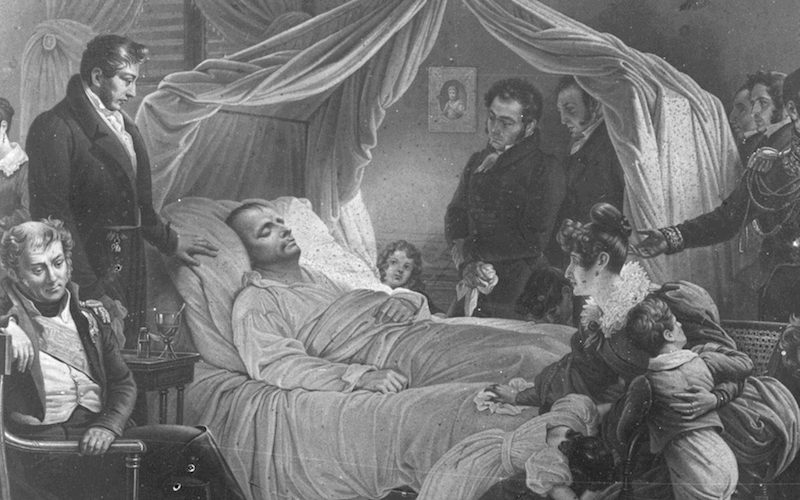

In these conditions, and in the light of these events, Napoleon Bonaparte’s appearance has been considered by some historians to have been that of the right person at the right time, and by others, as that of a visionary who definitively contributed to changing human history. Truly, besides political and military considerations, this man’s contribution to creating the first codified system of laws in France, a system which incorporated the ideas of the French Revolution, and which has influenced the judicial systems of many other countries to the present day, places Napoleon in the ranks of mankind’s great leaders.

The War of the First Coalition was the first attempt made by the European monarchies to defeat France’s revolutionary advance. The Habsburg dynasty and the royal family of Prussia were watching the events in France with concern. They clearly expressed their intention not to permit the spread of the ideas of the French Revolution and to support the Bourbon royal family. Great Britain joined this alliance. Between 1792 and 1797, great battles were carried out: on one hand, in the east, where the Prussian Kingdom and the Habsburg Empire tried to invade France, and on the other hand in the west, where the British laid siege to the port of Toulon and supported the revolt of the French monarchists in Vendée.

1 of 6

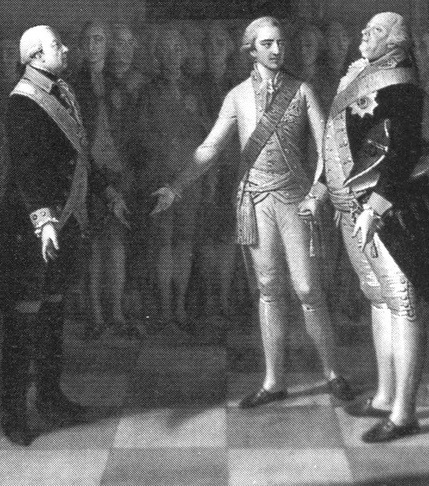

On the 27th of August 1791, the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold II, and king Frederick William II of Prussia, in consultation with the French nobles who had fled France after 1798, issued the Declaration of Pillnitz. In this, they expressed their interest in safeguarding the wellbeing of king Louis XVI and his family. They called attention to the grave consequences which would follow if their integrity were attacked. Leopold II considered the Declaration of Pillnitz to be a simple gesture to satisfy the requests of the exiled French nobles. Even so, in France it was interpreted as a serious threat to the revolution and the French Republic.

2 of 6

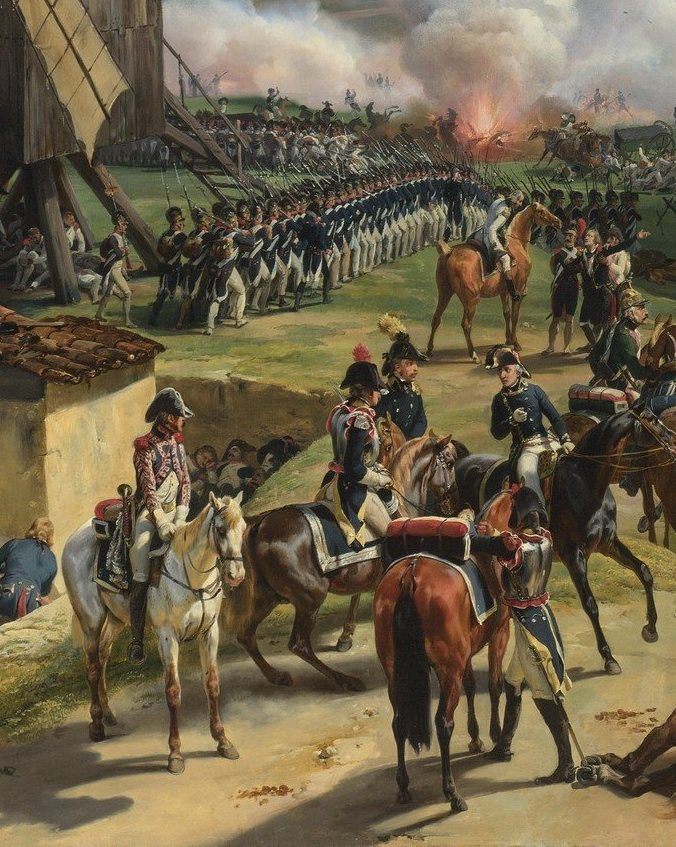

The war was left unresolved, and the French Republic was literally surrounded by enemy armies. In the following years, the success of the French armies grew. There were few changes on the Alpine border; the French republican army’s invasion of Piedmont was unsuccessful. On the Spanish border, the troops commanded by general Dugommier passed from defense to attack when they invaded Catalonia. On the northern front, the French armies obtained the greatest victories, pushing the Austrians, British and Dutch beyond the Rhine and occupying Belgium, Rhineland and southern Holland.

3 of 6

France issued an ultimatum, demanding the Habsburgs renounce all alliances hostile to the republic and withdraw their troops from the French border. The Austrian response was evasive, and the Constituent Assembly voted for war. The French prepared an immediate invasion of the Netherlands, which were ruled by the Habsburgs. They set off from the assumption that the local population would rise against the Austrian domination, as had happened in 1790. However, the revolution had profoundly disorganised the army, and the forces called up were insufficient for an invasion. Following the declaration of war, a large number of French soldiers deserted.

4 of 6

The Dutch rallied to the French appeal to arms against the monarchy and began the Batavian Revolution. Town after town was occupied by the French, the Dutch fleet was captured, and Stadtholder William V, prince of Orange, left the country. His authority was replaced by the parliamentary regime of the Batavian Republic, created by the French armies. Once the Netherlands had fallen under French influence, Prussia decided to leave the anti-republican coalition. It signed the Peace of Basel, giving up the Rhineland to France. In northern Italy, the victory at Loano gave France access to the Italian peninsula.

5 of 6

The Austrians and Prussians went on the offensive, entering France and occupying the strategic fortress of Verdun. The road to Paris seemed to lay open. However, on the 20th of September, at Valmy, the invaders were stopped by the troops of the French generals Dumouriez and Kellermann. Even though the battle was a tactical draw, it was a great boost to French morale. On the other hand, the Prussians realised that the campaign had gradually become longer and more costly than first estimated, so they decided to retreat. The following day, the monarchy was formally abolished. France was officially declared a republic.

6 of 6

The second half of the duration of this war was dominated Napoleon Bonaparte’s entry to the stage. This man, through campaigns in Italy and Egypt, consolidated the fight against European monarchies. Once the French Republic was stabilized, the war began to look more and more like a conflict for obtaining influence and political-economic control of the continent, than the anti-revolutionary battle it had been at the beginning.

- Emil Ludwig, trad. Eden Paul, Cedar Paul, Napoleon, Allen & Unwin London, Woking, 1927

- John S.C. Abbott, The History of Napoleon Bonaparte, Harper & Brothers Pub., New York, London, 1883

- William Milligan, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, The Century Company, New York, 1894

- Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Ramsay Weston Rhipps, Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, C. Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1890

- Gabriela Pantiș