Rise and fall

Great Britain broke the peace of Amiens and declared war on France. An English-Swedish accord followed, which became the first step towards the creation of the third Coalition. Subsequently, Great Britain signed an agreement with Russia. Austria also joined the Coalition, having been defeated twice by Napoleon and considering itself justified in not allowing French intervention in the domestic policy of the German States.

1 of 6

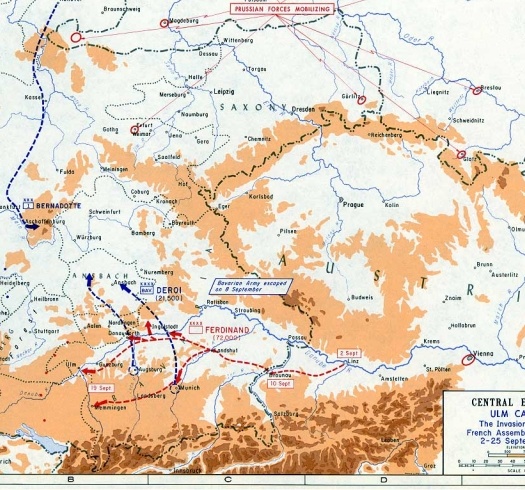

Before the formation of the third Coalition, Napoleon organized an army to invade Great Britain, ‘L’Armée d'Angleterre’, in Boulogne, in northern France. The invasion never took place, but these troops later became the core of the ‘Grand Armée’ in the following military operations. Aiming to strike before the Russians could come to Austria’s aid, Napoleon ordered his army across the Rhine in a forced march. The Austrian troops were concentrated around the fortress of Ulm, which the French troops had managed to surround in a huge outflanking maneuver.

2 of 6

In the battle of Wertingen, Austrian General Franz Auffenberg’s division was initially attacked and defeated by the cavalry corps of the French General Joachim Murat and the 5th Infantry Corps of General Jean Lannes. The next day, the commander of the Austrian army, Karl Mack von Leiberich, tried to cross the Danube and move north. He was defeated in the battle of Gunzburg by Jean-Pierre Firmin Malher’s division from the 6th Infantry Corps, commanded by the French General Michel Ney. After the battle, the French occupied a bridgehead on the southern bank of the Danube.

3 of 6

After this first confrontation, General Mack withdrew his army to Ulm; however he later tried to break through the northern French front. His troops were blocked by General Dupont de l’Etang’s division in the battle of Haslach-Jungingen. From that moment, the Austrian positions were completely surrounded. Thus, Napoleon fulfilled his objective of not permitting the Russian army to join up with the Austrian army.

4 of 6

The French continued to tighten the noose around the Austrian army. General Ney defeated a small corps commanded by the Austrian General Riesch, in the battle of Elchingen, the survivors of which retreated to Ulm. General Murat intercepted the troops of General Werneck. Over the next few days, Werneck’s corps was overwhelmed in a series of actions, at Langenau, Herbrechtingen, Nördlingen and Neresheim, and he later surrendered the rest of his troops. Out of all the Austrian generals, only Archduke Ferdinand Karl Joseph of Austria-Este and a few other generals managed to flee to Bohemia.

5 of 6

Mack’s entire army was surrounded in the fortress of Ulm. Later, he surrendered, with 25,000 men, 18 generals, 65 cannons and 40 banners. In less than 15 days, Napoleon’s army neutralized 60,000 Austrians and 30 generals. At the surrender, named the ‘Ulm Convention’, Mack offered his sword and introduced himself to Napoleon as ‘the unhappy General Mack.’ Bonaparte replied: “I give the unhappy general back his sword and his freedom, together with my best wishes to his Emperor.” Francis II, emperor of Austria, was not, however, as understanding. Karl Mack was tried by the Court Martial and condemned to two years of prison.

6 of 6

The Ulm Campaign was considered to be one of the best examples of a strategic victory. This campaign was won without a single major battle, which would have produced heavy losses for the French army. Everything was done to mislead the enemy. In his proclamation in the Army Bulletin, Napoleon declared: “Soldiers, I announced a long and hard fight. Due to the incoherent plans of the enemy however, we have obtained the same success without any risks. In 15 days, we have won a campaign.” Through the defeat of the Austrian army, Napoleon ensured the conquest of Vienna, which was occupied one month later.

Napoleon’s success on land was not replicated on the seas. The Battle of Trafalgar has remained in history as one of the most brilliant victories of the British Royal Navy. With this victory, Napoleon’s plans of invading Great Britain were completely abandoned. The Royal Navy dominated European waters up until the end of the Napoleonic wars.

1 of 6

Before this battle, Napoleon planned to break the British blockade using the French fleet. This fleet would unite with the allied vessels of the Spanish fleet and with the French naval forces from the Caribbean Sea. This reunion had the goal of safely attacking the British fleet, which was defending the English Channel. An important aspect of the maritime conflicts which followed was that, in contrast to the French, the British had very well-trained naval officers, an advantage which proved vital. The French naval officer corps was decimated during the French Revolution, which led to a much lower level of tactical expertise in battle.

2 of 6

The plan was put into action and the French fleet, commanded by Admiral Villeneuve, successfully broke through the British fleet’s blockade, commanded by Admiral Horatio Nelson. The English were looking for the French fleet in the Mediterranean Sea, erroneously assuming that Villeneuve was intending to sail towards Egypt. At the same time, the French fleet passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, joined up with the Spanish fleet and sailed, according to plan, for the Caribbean. Nelson realized that the French had crossed the Atlantic Ocean and set out in pursuit.

3 of 6

Villeneuve returned from the Caribbean with the intention of breaking the Brest blockade. Two of the Spanish ships under his command were captured during the battle of Cape Finisterre by a British squadron commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Calder, who had been sent to intercept the French-Spanish fleet. After these events, Villeneuve abandoned the plan and sailed towards southern Spain.

4 of 6

The British quickly pulled together a fleet of ships from those protecting the English Channel and sent them south. The fleet was commanded by Admiral Nelson, who ordered them to stay at a distance from the coast, waiting for the French to make the first move. In the meantime, Napoleon modified his initial plan and ordered Admiral Villeneuve to sail towards Naples. Villeneuve hesitated, aware of the disadvantages of a direct confrontation with the British fleet, especially since he had an ever-greater lack of provisions. After almost a month of delays, the French fleet left port.

5 of 6

Admiral Nelson’s fleet adopted a different battle formation than that usually used in naval tactical confrontations. Instead of forming a battle line which would engage the enemy fleet on a parallel line, Nelson decided to engage the French-Spanish fleet in a perpendicular formation, in two columns. Thus, he would cut the enemy line into three segments and destroy the middle segment of ships, between the two British columns. Then, the ships to the left and right of the British lines would be dispersed by destroying the command ship of the French-Spanish fleet in the central section.

6 of 6

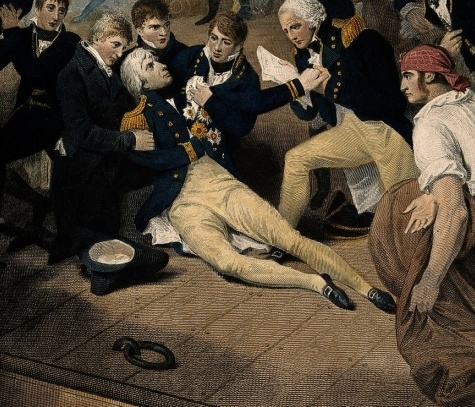

Nelson’s plan worked, although initially the British ships leading the two battle columns suffered losses, since they were exposed to lateral fire from the French. In short time, the British fleet finalized the maneuver and cut the enemy line into three sections, and then began a heavy bombardment of the French and Spanish ships. The superior naval abilities of the British also played their part, and out of the fleet of 41 French and Spanish ships, 21 were captured. Admiral Nelson was wounded and died shortly afterwards, his last words being: “For God and country!”

- Emil Ludwig, trad. Eden Paul, Cedar Paul, Napoleon, Allen & Unwin London, Woking, 1927

- John S.C. Abbott, The History of Napoleon Bonaparte, Harper & Brothers Pub., New York, London, 1883

- William Milligan, Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, The Century Company, New York, 1894

- Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Ramsay Weston Rhipps, Memoirs of Napoleon Bonaparte, C. Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1890