Kofun

Burial mounds, horse riders and the ascension of the Yamato clan

300 AD - 538 AD

The Kofun period starts right after the Iron Age agricultural society of the Yayoi. From all the warring kingdoms of the Yayoi, a clan emerges victorious. Its name is Yamato, the family which will establish the Japanese imperial line. This is why some historians name this timeline as Yamato. In order to strengthen their rule, Yamato leaders built an official Shinto religion and huge burial mounds for the political elite. Kofun is actually a Japanese terminology for burial mounds. At the end of the Kofun period, massive spiritual and technological imports from China brought a tremendous cultural revolution. Japan slowly began to be one of the most civilized and evolved nations of the world.

1 of 7

Burial mounds first appeared in central Honshu, a region where Yamato kings imposed their dominion. From there the practice spread into most of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu. Kingdoms and tribes from Hokkaido and southern Kyushu mostly preserved their own customs. The cold climate in Hokkaido discouraged further military expansion. Until modern times, the Hokkaido, Sakhalin and Kuril islands were the home of the Ainu tribes.

2 of 7

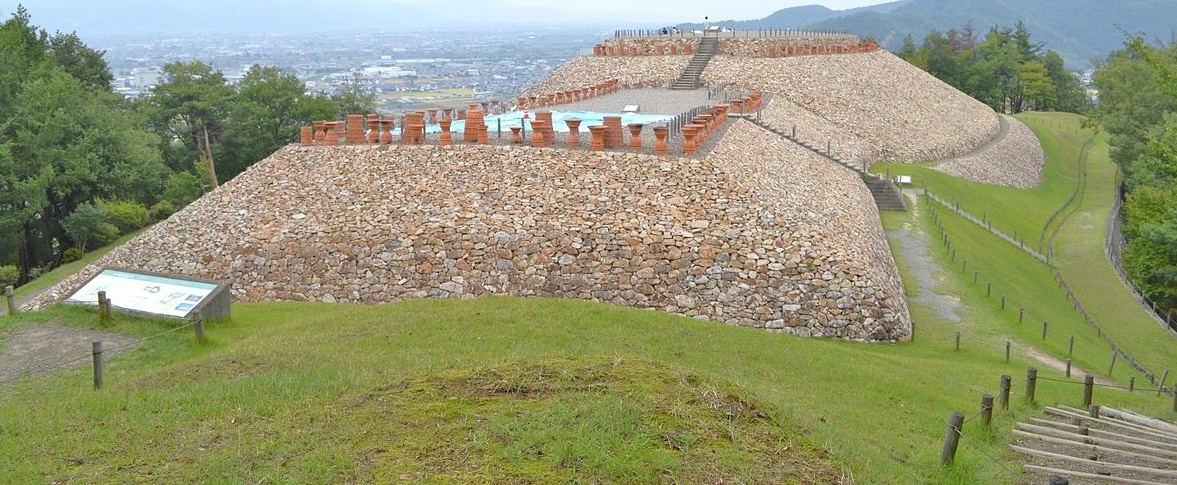

The sizes and purposes of burial mounds varied greatly in the different stages of the era. Early burial mounds were discovered as far back as the Late Yayoi period, but their scale was modest. As we go further into the Kofun jidai, archaeologists have discovered bigger graves with some valuable objects buried alongside the dead. Burial mounds from the Middle Kofun period even surpassed the dimensions of pyramids from ancient Egypt. An important person was buried in the center of the burial mound in a coffin or in a stone chamber. Next to the main room, numerous other chambers with jewels, weapons, statues and slaves were discovered.

3 of 7

The capital and main cities of the Yamato were located somewhere between today’s Kyoto, Osaka and Nara prefectures. Because of Shinto beliefs, the capital city was always moved after a king died. It was a cleansing of past mistakes and a preservation of the divine nature of Yamato rulers that should represent immortality in an institutional sense. Many times the heir of the state leader established a new capital from scratch with the goal of creating a new bond with the gods that could offer him blessings for a glorious rule.

4 of 7

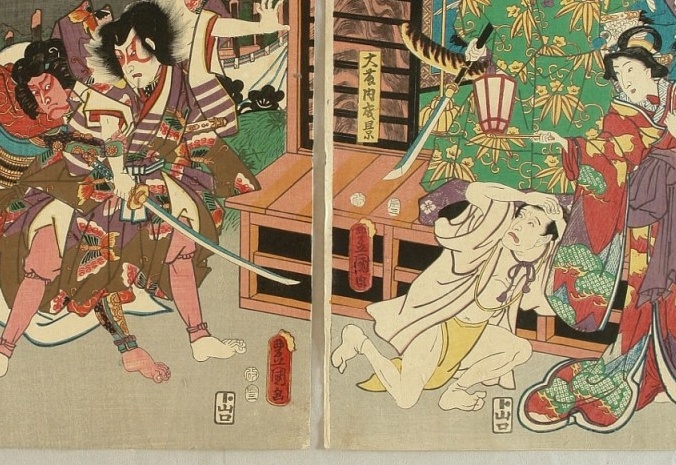

Primitive dogu clay figurines from the Jomon and the Yayoi were replaced by elaborate haniwa sculptures made from terracotta. These sculptures are the main source of inspiration for reconstructing what Yamato warriors looked like. Unlike dogu figurines that represented gods and fertility symbols, haniwa sculptures embody shapes of soldiers, aristocracy, horses and farmers. Most of them were discovered in mound burials destined for the political and religious elite. They were meant as offerings for Shinto deities.

5 of 7

In comparison with the Yayoi era, there were no major technological revolutions in the Kofun period. On the other hand, almost every technical means of production and artistic expression became far more complex. Weapons were made from improved iron forging technology, while bronze was used only for decorative and religious objects. Armor, helmets and shields were more effective in keeping soldiers alive in battle. Wet rice fields were cultivated on higher grounds and used elaborate irrigation systems, allowing a bigger supply of food and enhancing population growth.

6 of 7

For unknown reasons, the colossal burial mounds had a keyhole shape. Unfortunately for researchers, these complex structures corroded with the passing of time. Only signs of small mounds made of earth remain, but with the help of high tech excavations and DNA testing, archaeologists have succeeded in grasping an understanding of part of the ancient world. In total, more than 20,000 burial mounds have been discovered up until today.

7 of 7

Total population count doubled in the Kofun jidai from two million to four million inhabitants, Japan becoming one of the most densely populated regions of the ancient world. For example, in the Kofun jidai, the whole Roman Empire had an estimated population of fifty million people. Shintoism became a state religion that tried to unify and ameliorate the local differences in religious, political and social habits. It should be noted that the dominance of the Yamato was gradually obtained and firmly imposed only in the Late Kofun.

Separating Yayoi culture from Kofun culture is not an easy task for historians. Firstly, archaeologists discovered small burial mounds in the Late Yayoi, making the transition difficult to identify. Secondly, technology evolved but the whole period had no technical revolutions. In general, specialists highlight some main characteristics for understanding the changes in the era. Yayoi was a shamanistic, warlike and matriarchal society, while Kofun had an organized religion, was a patriarchal society and warfare was more limited by strong leaders.

1 of 5

The discussion is complicated by western historians who name the whole period from Kofun to Asuka as Yamato because the Yamato clan dominated Japanese politics in this timeline. Most Japanese historians do not agree with this classification because Yamato’s rule was not absolute and sometimes was very limited. Even more relevant is the end of Kofun, when the adoption of Buddhism created a spiritual revolution. Furthermore, the political and social reforms from the Asuka jidai radically transformed Japanese society, making the separation of Kofun from Asuka perfectly justified.

2 of 5

The transition from Yayoi to Kofun was marked by important changes. In Robert Ellwood’s opinion, the biggest religious reforms happened in the time of Emperor Sujin. Society shifted from matriarchy to patriarchy. Sujin prophecies replaced the foretelling role of the shamans. The divination of the sun goddess Amaterasu as the main deity was moved into other provinces, while a male god named ‘Yamato no-Okunidama’ became the main object of worship in the capital. The cosmogony of Shinto commutated from earth and land to mountains and the sky.

3 of 5

Japanese historians like Obayashi and Ishino consider climate change to be the main cause for the Yayoi fall. More exactly, they state that a colder climate in the Late Yayoi could have meant a very poor rice harvest, disease and famine. In this situation, the old Yayoi rituals and ceremonies could have been considered as bringing bad luck and being inefficient, so they were slowly replaced with new ceremonies. Another theory is related to economic development. If the society became more stratified, maybe the political elite didn’t want to continue the same communal rites as in the past.

4 of 5

Traditional historians think that Kofun marks a shift from female shamanistic and political dominance to the rule of male kings with divine rights. While Yayoi was a peaceful, agricultural and magico-religious era, the Kofun was more practical and warlike. Mark J. Hudson thinks that we should not generalize. ‘Late Kofun, yet I would argue that the latter description fits the Yayoi better than the former. Of course this is not to deny there may be some truth in such contrasts, but they should be viewed as theories to be tested rather than received knowledge.’

5 of 5

The Kofun era was outlined by the powerful Kingdom of Yamato which expanded into most of Japan and probably into south Korea. Unfortunately, no written records have been discovered in the Japanese archipelago. Although the military, diplomatic and economic activity in the Kofun jidai is far more intense, the Chinese chronicles give us fewer details about the Yamato than about the previous shamanistic kingdoms and tribes. From this perspective, and having certain parallels with the Dark Age of Europe, this timeline represents a mystery for historians.

- Paul Varley - Cultura japoneză, Humanitas, București, 2017

- Curtis Andressen - A short history of Japan from Samurai to Sony, Allen and Unwin, Canberra, 2002

- W. G. Beasley - The Japanese Experience. A short history of Japan, The Orion publishing group, London, 1999

- Kenneth Henshall - A history of Japan from Stone Age to Superpower, Palgrave Macmillan, New Zealand, 2012

- Donald Denoon, Mark Hudson, Gavan McCormack, Tessa Morris-Suzuki - Multicultural Japan: Palaeolithic to Postmodern, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2001

- Delmer M. Brown - The Cambridge History of Japan Volume 1, Ancient Japan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993

- P. C. Swann- The Art of Japan From the Jomon to the Tokugawa Period, Greystone Press, New York, 1966

- Noritake Tsuda - A history of Japanese Art. From Prehistory to the Taisho Period, Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2009

- Gina Lee Barnes - China, Korea and Japan The Rise of Civilization in East Asia, Thames and Hudson, New York, 1993

- Gina Lee Barnes - State formation in Japan. Emergence of a 4th-century ruling elite, Routledge, London, 2007

- Gina Lee Barnes - A Hypothesis for Early Kofun Rulership, Japan review 27, 2014, pp. 3-29

- Wontack Hong - Yayoi Wave, Kofun Wave, and Timing: The Formation of the Japanese People and Japanese Language, Korean Studies Vol. 29, 2005, pp. 1-29

- Mark Hudson - Rice, Bronze, and Chieftains: An Archaeology of Yayoi Ritual, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 1992, pp. 139-189

- Claudia Zancan - Decorated Tombs in Southwest Japan Behind the Identity and Socio-Political Developments of the Late Kofun Society in Kyushu, University of Leiden, Italy, 2013

- Naofumi Kishimoto - Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs, Urban Scope publication, vol. 4, 2013, pp. 1-21

- Allan G. Grapard - Shrines Registred in Ancient Japanese Law. Shinto or not?, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 29, 2002, pp. 209-232

- Shigefuji Teruyuki - International exchange of Kofun period chieftains of Munakata Region and Okinoshima rituals, Saga University, Faculty of Culture and Education, pp. 89-136

- Yamada Shunsuke - Kofun Period: Research trends 2013, Japanese Archaeological Association, 2013, pp. 1-20

- Nakakubo Tatsuo - Kofun Period, Japanese Journal of Archaeology 4, 2016, pp. 99-100

- Tanaka Yutaka - Kofun Period, Japanese Journal of Archaeology 2, 2014, pp. 80-81

- Tsujita Junichiro - The change in the distribution system of bronze mirrors at the beginning of Kofun period Japan: As seen from fragmented bronze mirrors, Bulletin of the Society for East Asian Archaeology, vol. 1, 2007, pp. 49-55

- Michael Ashkenazi - Handbook of Japanese Mythology, ABC -CLIO publishing, California, 2003