Japanese offensives 1941-1942

Japanese conquest of South-East Asia

1941-1942

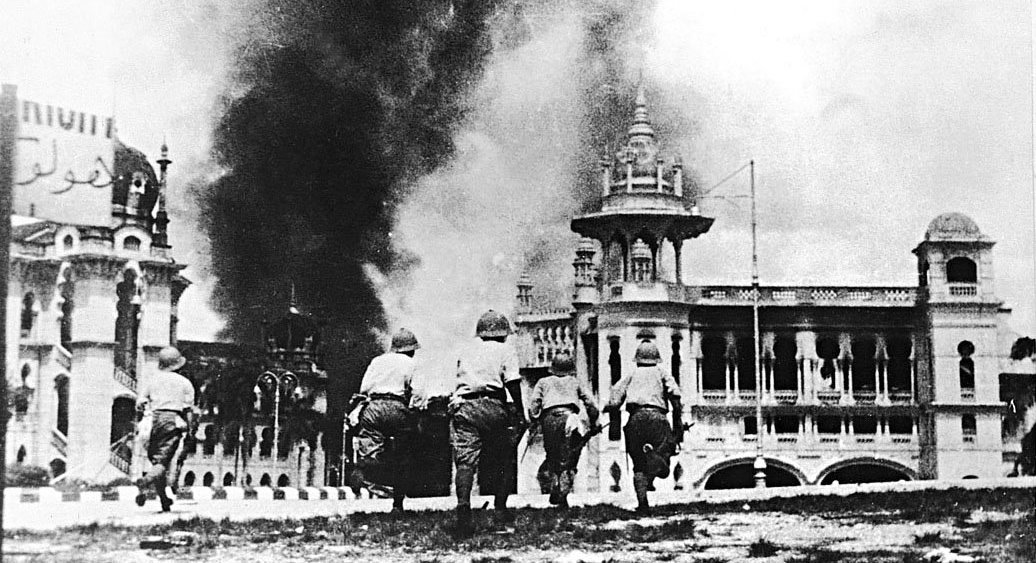

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese formulated a two-phase strategy for their conquest of South-East Asia. Hong Kong, Guam and Wake Island were to be captured immediately while troops were landing on the American Philippines and in British Malaya. Then, once the capacity of the Philippines and Malaya to interdict further operations had been neutralized, the Dutch East Indies and Burma would be occupied. Between December 1941 and April 1942, the six aircraft carriers of the First Air Fleet that attacked Pearl Harbor went on to attack Rabaul, Darwin, Colombo and Trincomalee, covering one third of the circumference of the globe and without losing a single ship.

1 of 6

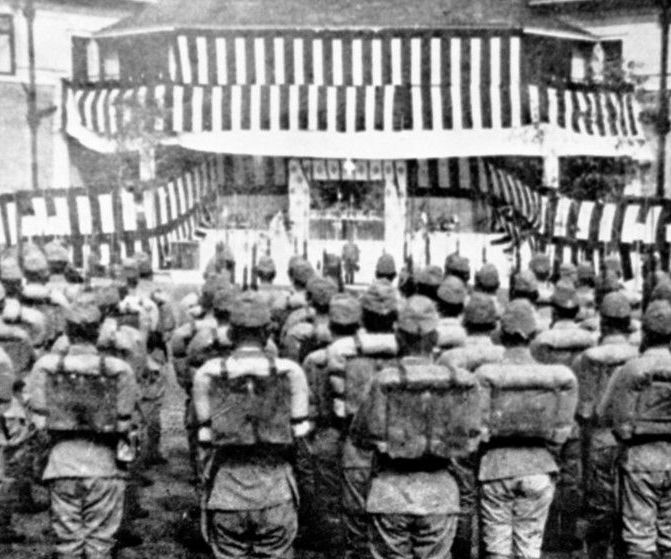

Many Japanese welcomed the war, which they believed offered their country its only honorable escape from beleaguerment. But it would be mistaken to imagine Japanese society as a monolith. Lt. Gen. Kuribayashi Tadamichi, who had spent two years in the United States, wrote to his wife asserting his strong opposition to challenging so mighty a foe on the battlefield: ‘Its industrial potential is huge, and its people are energetic and versatile. One must never underestimate the Americans’ fighting ability.’

2 of 6

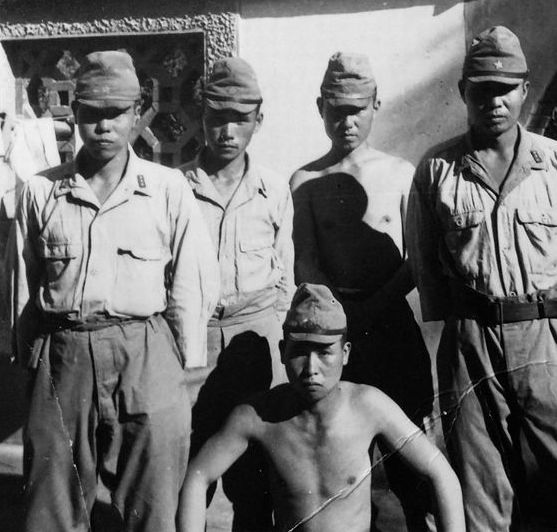

No one except the Japanese Army found much to remember fondly about the major campaigns that conquered Malaya and the Philippines, both hopelessly isolated by Japanese air and naval supremacy.

3 of 6

Japan’s 1941-42 successes against feeble Western resistance caused both sides to overrate the power of Hirohito’s nation. Just as Germany was not strong enough to defeat the Soviet Union, Japan was too weak to sustain its Asian conquests unless the West chose to acquiesce in early defeats. But this, like so much else, is more readily apparent today than it was seventy years ago, in the midst of Japanese triumphs.

4 of 6

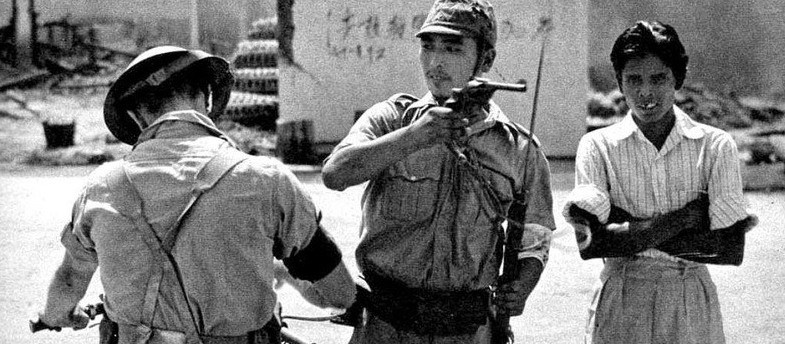

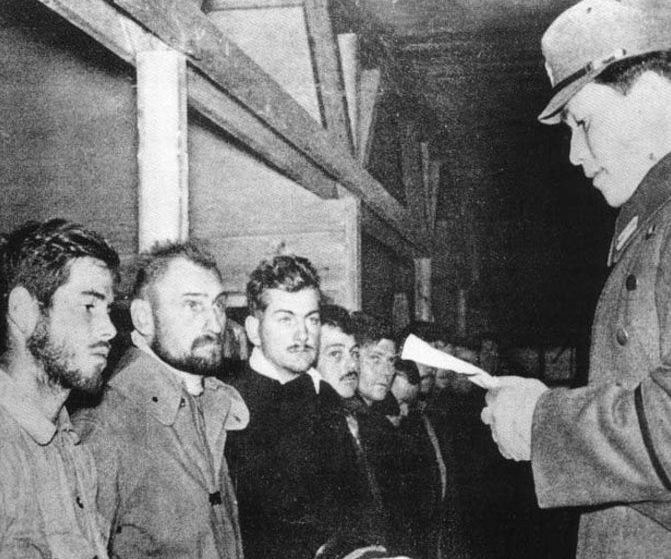

The cultural chasm between foes was exposed when British troops surrendered. They expected the mercy customarily offered by European armies, even those of the Nazis; instead, they were stunned to see their captors killing casualties incapable of walking, often also unwounded men and civilians. The teenage daughter of a Chinese teacher who brought food to an Argyll officer in his jungle hiding place in Malaya one day left a note in English for him about the Japanese: ‘They took my father and cut off his head. I will continue to feed you as long as I can.’

5 of 6

Within hours of the Pearl Harbor strike, the Japanese armed forces began six months of conquest that brought them to the gates of India and the sea approaches to Australia and Hawaii. The smaller objectives (measured by both geography and the size of the defense forces) fell quickly: Hong Kong, Guam, New Britain Island with its natural harbor of Rabaul, Bougainville and Buka with coastal plains for airfields in the northern Solomons, and the Gilbert Islands.

6 of 6

After the fall of Singapore, the myth of the British moral right to rule disappeared forever in Asia and Africa. Australia thereafter assumed that only the United States could be counted on to defeat Japan or any other Asian enemy. For the Japanese, it was the most thrilling of many exciting victories in 1942, for Britain had always been the hated and feared father of Japanese modernity.

The Japanese launching of war in East Asia was designed to secure control of the resources of Southeast Asia as rapidly as possible. The major objective was a rapid seizure of the Philippines and Malaya as a preparatory step for the conquest of the Dutch East Indies. Combined with an occupation of Burma and the seizure of added portions of New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Marshall and Gilbert Islands, this new empire would ensure that Japan could both control the resource-producing lands she coveted and have a perimeter of bases from which to defend that empire against any who might try to wrest it from her.

1 of 3

The detailed military plans to implement this program had been carefully worked out in the fall of 1941, but while they included careful schedules for the offensive operations, they were totally deficient in two critical ways: there was no agreed plan for going forward thereafter if the planned conquest succeeded; and there was no plan to go back if it failed. The Japanese assumed that their war would end when it had reached the perimeter of their newly-won empire. But there was never any prospect of this happening; had there ever been one, they had themselves eliminated it with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

2 of 3

The calculation that the Americans would never expend the blood and resources necessary to reconquer for others a whole host of islands and other places most of them had never heard of, and did not care about if they had, was invalidated by the way in which the Japanese had started war with the United States.

3 of 3

The decision to include war with the United States as a part of the move south was related to the belief that it was simply not safe to bypass the Philippines; and since the Japanese did not believe they could wait until the Americans left those islands in 1946, as the latter had already decided to do, those islands had to be invaded. Conquered by Japan, they would themselves provide an excellent base for the invasion of the Dutch East Indies and a fine station along the route into the southern empire.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011