Invasion of Normandy

Allies begin to liberate France

The invasion of Normandy, or the Normandy Campaign, was a battle fought between Germany and the Allies during World War 2. The Allied forces launched an amphibious and airborne assault on the French province of Normandy. After a successful D-Day, the first day of the invasion, the Allies were able to establish a beachhead in France and advance inland. The invasion was code named Operation Overlord. The Normandy campaign enabled the Allies to surround 50.000 Germans at the Falaise pocket. The campaign ended when French and American troops liberated Paris. Operation Overlord is considered to be the largest amphibious operation in history.

1 of 7

The Western Allies had decided to utilize the Italian campaign to help prepare for the invasion in the West. They would keep the German forces occupied in Italy and thus keep them away from both the Eastern Front and the invasion area. Also, the liberation of central Italy would provide them with air bases from which their bombers could reach the rest of German-occupied Europe. Finally, experienced divisions from the Italian theater would provide the needed push for the landing on the south coast of France, supporting the invasion of northern France.

2 of 7

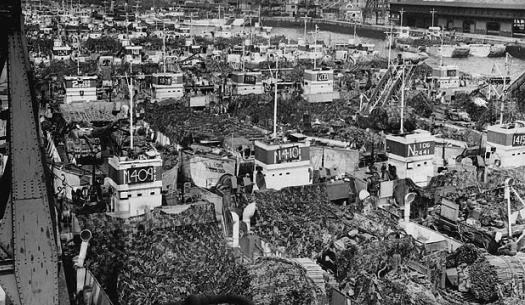

The full backing of the US and British governments for ‘Overlord’ was dramatically illustrated by the enormous commitment

of troops—over a million men—along with thousands of ships and planes to the enterprise. Along with the element of surprise, the sheer size of the Normandy landings was key to their success. Although the first day itself involved fewer troops going ashore than Operation Husky had in Sicily, overall they were the largest amphibious landings in world history by far.

3 of 7

Although it was clear that any large-scale amphibious landing on the heavily defended coastline of north-western Europe would be a major risk, the Allies did everything they possibly could to minimize military casualties through the employment of overwhelming force. This had the effect of hugely increasing the already high stakes. A major defeat in Normandy would almost certainly have caused the United States to abandon the Germany First policy, and turn to the Pacific War instead.

4 of 7

Amphibious operations had not enjoyed success in the Second World War up until that point. The attack on Dieppe had been a disaster. Salerno and Anzio had been near-disasters. Torch had been extremely lucky with the tides, but it was not undertaken against the Germans. Further back, Gallipoli (during World War 1) haunted the minds of many, not least its prime author, Churchill.

5 of 7

Even on top of all the Allied planning, however, luck would be required. ‘We shall require all the help that God can give us,’ Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, commander of all naval forces for the operation, noted in his diary the night before. ‘I cannot believe that this will not be forthcoming.’

6 of 7

As soon as the beachheads were secure, troops would pour into Normandy, principally Patton’s US Third Army and Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar’s Canadian First Army. The plan was for the 21st Army Group to establish positions stretching from the Loire to the Seine, take Cherbourg and Brest, and then liberate the rest of France and march to Germany. The Allied plan would be backed up by enormous air power, co-ordinated by Eisenhower’s deputy supreme commander, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder.

7 of 7

Operation Overlord, the cross-Channel landing on the shores of Normandy, represented four long years of preparation. The scale

of its success placed the democratic powers back in Central Europe, a political position of critical importance in the second half of the century.

At the Trident Conference, the Americans, after a long and heated debate, finally obtained Britain's agreement for a target date for the cross-Channel invasion. However, the British were still reluctant regarding the potential success of the campaign as they feared that even if successful the troops would become bogged down in France and suffer heavy casualties. The Allies planned to storm the coast of Normandy near Caen, and then advance towards the important port of Cherbourg.

1 of 5

Churchill constantly went back and forth between a firm endorsement in principle of the cross-Channel operation and a concern that the opportunities in the Mediterranean theater must be exploited. Time and time again, a foreboding sense came to him that a renewed battle in north-western Europe would involve staggering casualties if the landing failed or if the troops, once ashore, became involved in a lengthy campaign reminiscent of World War I.

2 of 5

Field Marshal Brooke, who on other occasions restrained the Prime Minister's impulsive advocacy of all sorts of expeditions and projects, was most reluctant to delay Mediterranean operations in favor of a future project which he was scheduled to command but for which he evidently did not consider the prerequisites to be in place.

3 of 5

The USA believed that unless the energies of the Western Powers were tied to a firm date, with the operational, shipping, production, and training schedules geared to that date, the Allied invasion plans would end up being postponed indefinitely. Then the United States would either have to carry it out by itself or shift to a Pacific First strategy.

4 of 5

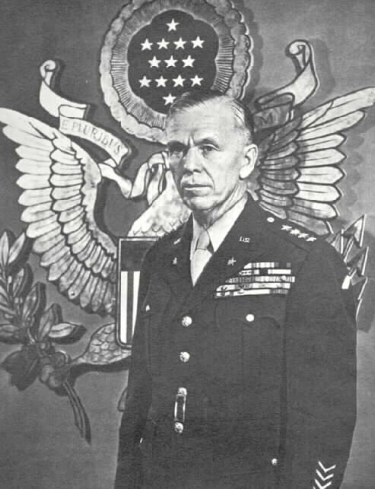

President Roosevelt's growing confidence in the advice of General Marshall and the growing strength of the United States helped make him absolutely determined to get a firm and final commitment for Operation ‘Overlord’, now with an American rather than a British commander.

5 of 5

General Frederick Morgan and his staff had been at work preparing an invasion plan. This plan was ready at the Quadrant Conference. It designated the beaches near Caen as the assault site, and called for major supply drops over the beaches. It stipulated an early effort to seize the port of Cherbourg, set forth the need to have separate sectors both during the assault and afterwards for the British and the US units, with the latter on the right flank to facilitate reinforcements. The plan stressed that it was essential to crush the German fighter planes in the West.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Rebecca Mace