February Revolution

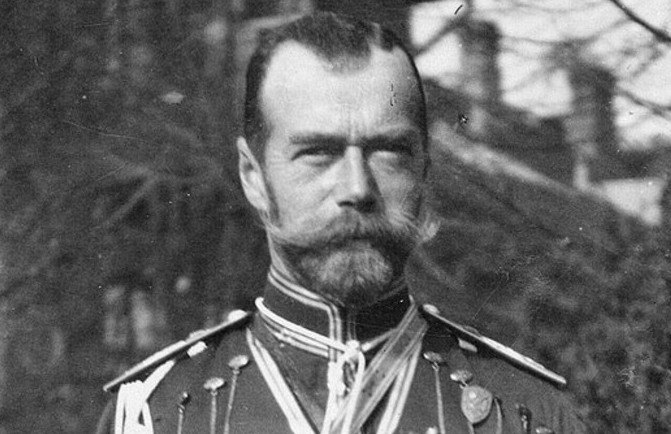

The Russian Tsar is removed from power

8 - 19 March 1917

The February Revolution was the first of two revolutions that took place in Russia in 1917. The main event of the revolution took place in Petrograd, present day St. Petersburg, then the capital of the Russian Empire. Discontent against the monarchy erupted in mass protests against food rationing. The revolution ended with the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the end of Imperial Russia. It is worth mentioning that the revolution is named the February Revolution, even though its events took place in March. The difference is explained by the Russian use of the Julian calendar instead of the Gregorian calendar. The Gregorian calendar was adopted by Russia later that year, after the October Revolution.

1 of 4

Entente efforts for 1917 were concentrated on General Robert Nivelle’s ambitious plans for a war-winning French offensive in the Champagne area, supported by a diversionary attack by the British at Arras. Yet a prominent role was still envisaged for the Russians. They were expected to place further pressure on the Germans by launching a major new spring offensive on the Eastern Front. The Russians cautiously insisted that May 1917 would be the earliest they would be ready to attack. But by then everything would have changed.

2 of 4

The Tsar himself was oblivious to the threat; he ruled by divine right and was therefore above such mundane considerations. Meanwhile, all about him his regime was falling apart with amazing rapidity. Political demonstrations multiplied exponentially and there was ever-increasing vigor in the protesters’ demands for food, political change and, increasingly, direct action.

3 of 4

Incompetence and corruption blossomed unfettered, while at the center the Tsar was publicly embarrassed by the adherence of the Tsarina Alexandra to the ludicrous cult of Rasputin, an unhinged religious mystic with a penchant for irreligious pursuits. The whole despotic system of government was resting on just a few weak individuals. Russia was being hollowed out from within, and the vacuum at the center was creating dangerous instability.

4 of 4

As more and more military units began to go over wholesale to the revolutionaries, the functionaries of Imperial government found themselves subverted on all sides. Many fled, while those who overtly resisted risked their lives. By the time General Mikhail Alekseyev had returned from sick leave to resume his position as Chief of General Staff, he could offer little support to the beleaguered Tsar. In 1905 the Russian Army had put down a revolution, but in 1917 it both lacked the enthusiasm and was far too occupied with the war to open fire on the people.

Discontent within the Army was only a small part of the story. The Russian home front was gradually collapsing under the intolerable strain of war. The Tsarist government did not have the flexibility necessary to cope with the plague of economic, political and social problems that infected the land. The Tsar himself perceived any form of democracy as a threat to his regime. Rather than introducing an increased measure of liberalism, he was more attracted to the idea of the total dissolution of even the tokenistic Duma.

1 of 4

Appointments to positions of considerable authority were routinely assigned by the Tsar on the grounds of either naked favoritism or the authoritarian credentials of the candidate. Spy scares raged through society, with particular suspicion falling on any Russian general unfortunate enough to have a Germanic name.

2 of 4

The Russian armies may have been short of food rations, but they actually had priority in the allotment of the harvests; the result was increasing food shortages in the major cities. Production of agricultural food stuffs was generally in sharp decline. As the populations of the cities began to starve, popular discontent spread.

3 of 4

Inflation was soaring, but wages remained static, so the poor were priced out of the market for whatever food was available. In a severe winter there were also shortages of fuel. The result was food riots, widespread industrial strikes and open political dissent, with most participants unanimous in blaming the Tsar and his government for their suffering.

4 of 4

In January 1917, an agent of the secret police reported that ‘Children are starving in the most literal sense of the word. A revolution’, he concluded, ‘if it takes place will be spontaneous, quite likely a hunger riot.’

Eastern Front after the February revolution

After the February Revolution and the overthrow of the Tsar, the new Provisional Government decided to stage yet another offensive against the Central Powers.

Bolshevik Revolution and the End of World War One on the Eastern Front

The October Revolution was orchestrated by the Bolsheviks in Petrograd, under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. A peace treaty was signed at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Rodney P. Carlisle, World War I, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003

- Norman Stone, The Eastern Front 1914-1917, Penguin Books, London, 1998